LA BATTAGLIA DI LEGNANO

Libretto: Salvatore Cammarano

Premièr at Teatro Argentina, Rome – 27 January 1849

Stage director: Franco Enriquez

Maestri collaboratori / Stage Accompanists: Maria Concetta Balducci, Gino Bianchi Rosa, Gianni Del Testa, Aldo Faldi, Erasmo Ghiglia, Pietro Margarito, Alberto Ventura

Direttore di scena / Stage Manager: Walter Boccaccini

Maestro suggeritore / Prompter: Luigi Morosini

Direttore dell'allestimento scenico /Production Manager: Piero Caliterna

Scenografi [realizzatori] / Set Designers [Realisation]: Giovanni Broggi, Bruno Mello, Giambattista Santoni

Collaboratore alla scenografia / Assistant Set Designerr: Giuseppe Santini

Capo macchinista / Chief Technician: Roberto Matteini

Vice capo macchinista / Assistant Stage Technician: Renato Ciulli

Capo elettricista / Chief Electrician: Aldo Santini

Costumi / Costumes: Cerratelli

Attrezzi / Props: Tani

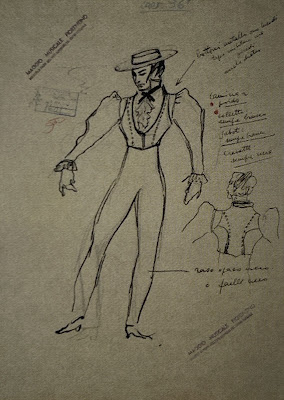

Frederick Barbarossa PAOLO WASHINGTON bass

The Mayor of Como MARIO FROSINI bass

Rolando Duke of Milan GIUSEPPE TADDEI baritone

Lida his wife LEYLA GENCER soprano [Role debut]

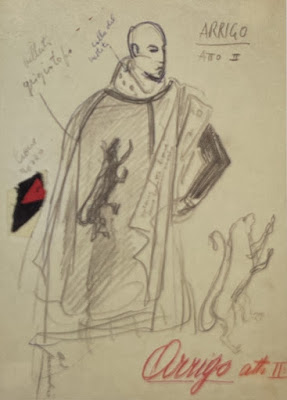

Arrigo a warrior from Verona GASTON LIMARILLI tenor

Marcovaldo a German prisoner GIORGIO GIORGETTI baritone

Imelda Lida’s servant OLGA CAROSSI mezzo-soprano

A Herald ALBERTO LOTTI tenor

Time: Twelfth Century

† Recording date

Parte Il / Act II: Barbarossa / Barbarossa

Parte III / Act III: L'infamia / Infamy

Parte IV / Act IV: Morire per la Patria / To die for the Fatherland

Recording Excerpts [1959.05.10]

FROM CD BOOKLET

The production which inaugurated the Maggio Musicale was of no less significance considering that present in the Teatro della Pergola (the Comunale was closed for extensive renovation) was the then President of the Republic Giovanni Gronchi, giving the institutional seal of approval to one of the many cultural events that put the Maggio in its heyday at the forefront of the revival. Franco Enriquez was the director, while the young Attilio Colonello was responsible for the set and costume design; the latter to sumptuous effect, providing a spectacle memorable for its visual impact, even though contemporary records indicate that the enthusiasm of other inaugurations was lacking, and the invited guests present were fewer than expected.

Credit for the success of a work which at the time had fallen out of favour is due to the indefatigable and expert endeavours in promoting culture as well as bringing it to fruition undertaken by Vittorio Gui in Florence, firstly as founder and artistic director of the Maggio Musicale and then, from the 1950s onwards, as an impassioned discoverer of forgotten works from the repertoire of Rossini and Verdi, which thanks to him would return to the scene in pioneering future productions with a more consistent presence on stages in Italy and abroad. His conducting, specifically of this Battaglia di Legnano, initiated an approach to Verdi committed to doing justice to what are the two distinct, though thoroughly intertwined, essential features of an opera chronologically placed within the period that brings to an end Verdi's so-called "prison years" but also puts him at the beginning of what Andrea Della Corte defined as "Verdi's great achievement in intense expressionism,

which will mark the end of arid recitative and the emergence of a new drama and plasticity in cantilenas." Gui understands that the key to best appreciating a score like La battaglia di Legnano is in seeking a balance of sound poised to capture the choral expression of the taking of oaths and the civic, religious and military ceremonies celebrated by the Lombard League in reaction to the Germanic invasion of Federico Barbarossa as a consequence of an outpouring of national pride, but also as an ideal way of connecting with the private dramas of the characters, evident in the almost bourgeois adulterous affair familiar from the many melodramas of early Verdi. And it is interesting to note how the noisy patriotic background with which Gui infuses typical Verdian flashes that are never revealed externally, but rather through a sinister shading that attenuates the vehement vibration of dynamics and rhythms (this also happens in the powerful impetus given to the Sinfonia, with the martial fanfare of the Lombard League recurring in different parts of the opera) leaves the right amount of space for the noble recitativo energised by the words declaimed and enriching them with a dramatic tone that goes well beyond the intentions inspired by the Risorgimento of an opera in which intimate matters find collective solutions in patriotic love, drawing on that emotion to mollify the errors and misery of life, thus propelling La Battaglia di Legnano's singular two-dimensional dramaturgy.

Confirmation of how Gui's strategy miraculously resolves the dramatic-expressive issues of a work at the time almost ignored, but ready to be rediscovered and appreciated for its many authentic values, is corroborated by the company of singers chosen for the occasion. Vittorio Gui wanted for the part of Lida an already established soprano, Leyla Gencer, whose versatility in choice of repertoire combined with her willingness to take on the role of the so-called virtuoso dramatic soprano, helped her to resolve all the difficulties of a role that she later reprised with equal success in other Italian theatres: in the same year at the Fenice in Venice and then at the Teatro Verdi in Trieste in 1963. Here at the height of her powers, Gencer offers a study in how her voice can draw on technical resources to shape a Lida pathetically immersed in powerfully expressive and evocative lyricism. In her parting aria "Quante volte come un dono", in which her mourning for the loss of her loved ones killed in war becomes a melody that traces with moving unselfconsciousness her heartfelt grief, Gencer displays singing of much poignancy playing on the highly refined dynamic between piano and pianissimo which in the acute register, with flute-like notes of perfect precision, charge the moment with a spell in which the finesse is not pure virtuosic exhibitionism, but a sonic distillation of a melancholy at once reserved and proud. It is easy to get the same sensation in the cabaletta that follows, "A frenarti, o cor, nel petto", when hope returns to her heart with the news that her beloved Arrigo is alive and not killed on the battlefield as she had believed. Also, in the passages infused with the trembling of authentic drama, as in the duet with Arrigo that closes Act I, or in the trio in Act III, the propensity for sentiment is never an end in itself because it is embellished by the necessity for breadth and passion, as happens in the moments of more daring virtuosity. In particular, to admire the character of her singing, just listen to how certain phrases of the duet with Imelda in Act III are handled: where, by means of free declamation she begs the trusty maidservant to deliver a note to Arrigo to plead for a meeting to rekindle their old love. In the midst of the convulsive turmoil that Lida, assailed by dark presentiments, finds herself, there are phrases such as "Questo foglio stornar potria cotanta sciagura" and "Che non ti scerna occhio mortal d'Arrigo varcar la soglia!", which Gencer delivers with pure lyricism, never forgetting to alternate with the fervent hope for the return of her beloved, the necessary support of incisive and agitated dramatic excitement which is an inescapable characteristic of this character, as with many other soprano parts in early Verdi.

Another undoubted highlight of this production was Giuseppe Taddei in the role of Rolando, closest friend of Arrigo and betrayed husband of Lida, in who’s singing the development of the character's feelings are brought out. There is the anger of a man who is told of his wife's infidelity by his rediscovered best friend and unleashes his fury in the Act III cabaletta, "Ahi! scellerate alme d'inferno". In the next scene he declaims excitedly on repeated notes his intentions for revenge in "Ah! d'un consorte, o perfidi, scempio faceste orrendo!...", then challenges Arrigo with menacing rage and, in the trio that follows, considers in more devious tones locking up his rival in the tower ("No. Vendetta d'un momento sarebbe il trucidarti..."), staining the culprit with the infamy that the Act bears as its title. But it is not in these passages that one can admire the fundamental contribution that Taddei brought, in the years after the Second World War, to a Verdi voice that seemed to have forgotten the lessons of the nineteenth century and was no longer looking to vocal models contaminated by the school of verismo, with all the consequences in terms of loss of flexibility in favour of over elucidated singing. Taddei, on the contrary, chose a more demanding approach, that of preserving a bel canto tradition which required singing in a whisper, shaped by mellow phrasing and on the nobility of a legato and melancholic vocal line. All of this was used to characterise a Rolando acting not so much on the violence of the betrayed husband and his wounded honour but, as it must be, on the elegance of singing which has moments of rare evocativeness in giving voice to the high moral significance of family affections. The culmination of all this is reached in the middle of Act III, when Rolando, on the verge of departing for war, entrusts to his wife's care the upbringing of their son in the event that he dies on the battlefield. The affectionate inflection of his "O figlio!...", the trusting relinquishment in saying to his wife "Tu resti insegnatrice di virtude a lui" and the proud sentiment employed in "Digli ch'è sangue italico", thus urging his mother to teach him respect for God and love of country, form part of the general sentimental tone that in Taddei's mouth becomes a masterpiece of delicate articulation, like the caress of a silk glove, reflecting the protective and formative value attributed to the virtues acquired in domesticity. This is a quality confirmed in the following aria "Se al nuovo di pugnando", accompanied by the orchestra under Gui with aristocratic restraint, when Rolando entrusts wife and son to his friend Arrigo before joining the soldiers of the Lombard League, still unaware of the betrayal that he will soon discover; he does so with a light and noble tone, which in the progressive rise to the high note of the phrase "esser tu dèi per loro l'angelo tutelar!" finds Taddei skilful in sweetening the sounds with intimate delicacy, heartfelt and moving, always attentive to the meaning of the words, as it was customary to do on the part of a singer who knew every secret of Verdi's dramatic language, already applied to an early opera such as this one.

Unlike Taddei, Gastone Limarilli, in the role of Arrigo, which Verdi conceived for his favourite Gaetano Fraschini, performer but also creator of several roles in his operas, among which Riccardo in Un ballo in maschera, lends his glossy tenor voice, with its exceptional silvery timbre to a role which, at the start of the opera, requires tender and delicate expression for the aria "La pia materna mano". Here Limarilli displays the spontaneous generosity of a voice that to finesse prefers the ever-sincere ring of an outpouring of song, not stentorian but of incisive clarity, which in the final scene with the death of Arrigo finds just the right tone in the opera's key phrase "Chi muore per la patria alma sì rea non ha!", which he sings with passion and vigour, not forgetting to give a hint of a mezza voce that is exactly appropriate in "Siccome è puro un Angelo il cor di Lida è puro...", with which he reassures his friend Rolando of the goodness of his wife before redeeming himself and his faults in the name of love of country. It is the kind of singing that in its ardent high surges finds the best side of his vocal talent.

The opera's choral and patriotic slant is enhanced by the other performers, arrayed against the enemy, the German Emperor Federico Barbarossa, here an austere Paolo Washington. After listening, you are assured of how fundamental the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino was in contributing to the writing of historic chapters in the course of the rediscovery and practical execution of the works of Verdi, as the many other performances after this one testify. It was amongst the first but already significant examples paving the way for the rebirth of modern Verdi, still not philological, yet ready for the re-evaluation of operas until that moment forgotten or considered minor works.

The fortunes of La battaglia di Legnano in this century have depended greatly, as is the case with other minor works by Verdi, on that desire to rediscover forgotten works which has been one of the principal features of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino from the beginning. In fact. after a revival at the Teatro Regio in Parma in 1951, Florence's Teatro Comunale (which owing to restoration work had for some years been temporarily housed in the Teatro della Pergola) presented it as the inaugural opera of the XXII Maggio Musicale in 1959. With a truly splendid cast, guided by a director of the calibre of Franco Enriquez and a thoroughbred Verdian conductor, Vittorio Gui, who had already been involved in other important Verdi revivals in years of particular splendour for the festival (from Nabucco in 1933 to a memorable Macbeth in 1951). This recording gives us the full measure of Vittorio Gui’s emotional, at ties impetuous reading of Verdi, already evident in the tense, urgent overture. At the same time, he by no means ignores the stately massiveness of the choral episodes or the almost Bellini-like lyrical effusions that punctuate the action.