This recital is intended to be the artistic testament of Leyla Gencer, as it goes back to one of the last concerts given by the Turkish soprano, thirty-five years after her 1950 debut in Ankara in Cavalleria Rusticana. Since that Santuzza, a lot of water had flowed under the bridge and for Giannina Arangi-Lombardi’s pupil no whim had remained unsatisfied, in spite of the fact that her agile, light vocality initially seemed to classify her among the ranks of lyric-light sopranos. In fact, Gencer didn’t seem to care about the vocal classifications, which only Maria Callas was glamorously demolishing in that period and, thanks to her exclusive technique and a very audacious character, she ventured into th most varied roles and genres. She did justice to the best-known parts, such as Butterfly, Tosca, Liu or the two Verdi Leonoras, but also tackled Violetta – where her unusual potentiality for that period was noticed - and didn’t disdain modern rarities such as Menotti’s Il Console, Rocca’s Monte Ivnor, Dialogues des Carmélites by Poulenc and L’assassinio nella cattedrale by Pizzetti, the last two of which debuted at La Scala with her. This was something more than mere versatility and was born out with her unexpected debut (replacing Callas in San Francisco) Lucia di Lammermoor in ‘57. At that time, no Tosca or Leonara (apart from Callas) could have at all imagined such a daring transformation, extricating herself from Donizetti’s virtuosities and reaching up to dizzy heights of the top E flats. This came naturally to Gencer, even if bluffed her way into the role, as she didn’t in fact know the part. And even if in endless “catalogue”, Lucia was a role she only tackled again on other two occasions, it was nevertheless what was needed to show audiences (and in fact herself as well) how her unusual vocality could be best put to use.

This resulted in Gencer being chosen as the indispensable singer for the revival of the extremely demanding operas from Verdi’s early period (I due Foscari, La Battaglio di Legnano, Jérusalem and above all Macbeth), while singer gradually developed her specialization in Bel canto with Bellini (La sonnambula, I Puritani, Beatrice di Tenda and lastly Norma) and in particular with Donizetti where she started with Anna Bolena and Poliuto, as had Callas. In fact the Donizetti “bug” remained inactive for several more years, during which Gencer was frequently to be seen indiscriminately performing Aida, the Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro, Francesca da Rimini, Gilda, Donna Anna and Amelia in Un ballo in maschera.

In 1964 however the die was cast, and with a triumphant Elisabatta in Roberto Devereux, Gencer ensured herself the monopoly of a repertoire all her own, comprising exciting rediscoveries of Donizetti roles. Then came the Borgias, Stuards, Antonia in Belisario, Caterina Comaro, Paulina in Les Martyrs, which identified the Turkish soprano as a Donizetti reference point, even before the success of Caballé, Sills and Sutherland in the same roles.

This “label” however didn’t prevent her from playing Alceste one day and the next Gioconda, Medea or Mayr, Rossini’s Elisabetta and Spontini’s Agnese with chameleon-like gusto, not to mention the fact that the warlike Verdi found in Attila, Ernani and Vespri proved a pastime too irresistable to turn down. As one can imagine, boredom certainly wasn’t one of Gencer’s qualities, even if all this versatility didn’t depend entirely on a desire to avoid all obvious choices, but above all speculative curiosity (supported by very refined culture) and in particular her subjugating prima donna personality. It’s no coincidence that the series of queens formed the framework of Gencer’s repertoire, for the regal authority that characterized this soprano’s magnetism theatrical power from the outset. Temperament alone would’ve of course been useless without support of a superlative technique, which enabled her voice, which was anything but powerful as volume was concerned (but projected wonderfully on stage) and whose colur wasn’t dramatic (altough the accent definitly was) to undertake the hardest most contrasting roles in the soprano repertoire. The desire to “invent” a credible voice for the parts she was headily attracted to definitely compelled Gencer to come to compromises, such as some clearly “poitrinés” sounds in the lower register, her voice’s explosions on the high notes and the famous coups de glotte in the attack of the pianissimos, which she managed to transform into a highly personal trademark, thanks to her charisma. This change is noticeable in Gencer’s numerous recordings and can be dated around 1960: in fact, when comparing the same role in editions before and after that year (i.e. Anna Bolena, Amelia in Simone, Leonora in La forza del destino and Lidia in La Battaglia di Legnano), it’s possible to notice an emission that from the floating lightness, the concentrated low sounds and the vaporous atmosphere when handling the higher tessituras, gradually assumed the intensity, power and tension of effective dramatic incisiveness.

The new Gencer didn’t disown the young Gencer, even though nevertheless forcing her natural features, even if maintaining vigilant technical control and achieving an equally authentic vocal physiognomy. The performer’s unprejudiced generosity definitely didn’t worry about putting to her vocal chords to the test: they were very flexible, but definitely not made of steel, so around the mid sixties the first signs of vocal fatigue made themselves heard, with a consequent reduction of theatre recitals, until her last Lady Macbeth, staged in Leghorn in 1980. The singer’s activity didn’t stop there however, since she held numerous delightful concerts, among which her skill in handling a role reappeared for the last time with the prima donna star of Prova di un'opera seria by Gnecco at the 1983 Venice Carnival.

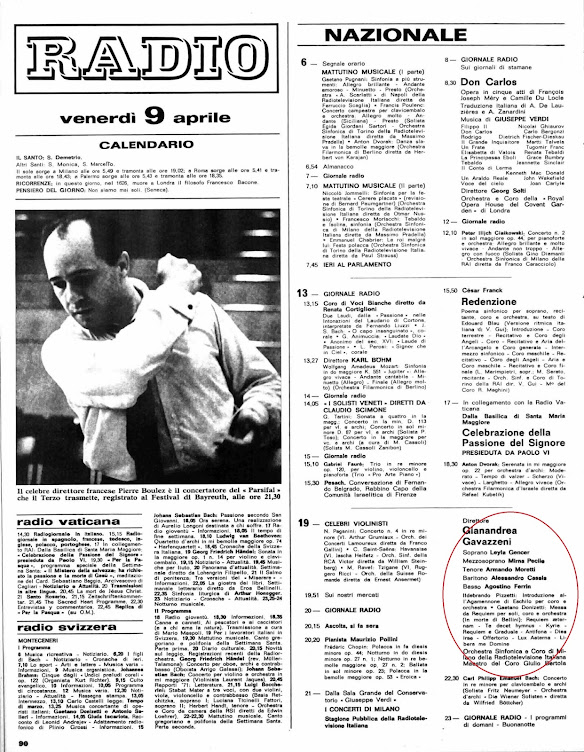

These weren’t years of melancholic withdrawal, as was seen from the still audacious choices proposed in these recitals’ programs, but on the contrary offered the great opera diva a period for rethinking her vocality and experimenting other directions. Gencer in fact wisely retraced her steps, trying to recover the beautiful fleeting emission of her early years, which the succession of numerous violent satanic roles had altered through time. Incredibly, she succeeded and the miracle occurred for her tardy Paris debut in 1980, with a triumphantly acclaimed recital at the Athenée, followed by one in ‘8l (already released by Bongiovanni: GB 2523-2), another in ‘83 and lastly this one, held on 29th April l985.

The refinement of the program, divided between 18th and early 19th century composers, is the exclusive choice of many ofthe pieces, which at that time were authentic rarities. The prevailing pathetic side favours the careful thoughtful emission of the voice, which Gencer manages to control with exquisite skill, in both the intense pianissimos with which she handles the jumps to the high notes of “Sposa. son disprezzata” from Vivaldi’s Bajazet and the repeated delicate agility of “Oh! Had I Jubal’s lyre” from Haendel’s Joshua. Afterward the nobility of the accent prevails, maintaining austere majesty even in the tearful abandon, taking the most stimulating occasions in a theatrical piece such as Haydn’s Arianna a Naxos cantata. Here the authority of the recitative, so skilfully alternated between ceremony and pathetic tenderness, introduces the lyricism of the catabile, repeated in pianissimo to touching effect and concluded, in an agitated atmosphere, by the stinging violence of that “barbarol”, in which the extremely cutting R’s reveal all the abandoned protagonist’s resentment.

The second part is even more stimulating, in which some irresistible queens reappear (Golconda was to be Gencer’s last Donizetti performance, a couple of years before the opera’s revival in Ravenna) and with the only “en travestti” role performed by the Turkish prima donna, Armand in Il crociato in Egitto, here proposed in an aria written expressly by Meyerbeer for Giuditta Pasta, on occasion of a Parisian recital in 1825. Compared with the first part it’s already possible to hear Gencer’s stylistic subtlety in the choice of a more romantic accent, more sentimental abandon and a more open melodramatic theatricalness. And one is surprised by how the singer still ventures into daring cadenzas precious variations (e.g. the one in the reprise of “Dopo l’oscuro nembo” a magnificent anticipation by Bellini of Juliet’s cavatina in I Capuleti), brilliant fiorituras, such as in the martial Meyerbeer cabaletta, which reveals a Gencer who is unexpectedly virtuoso, precise and at the same time amused.

The encores are another surprise, with a self-ironic Rossini piece entitled “Siete turchi” (You’re Turkish), capriciously lifted from the Fiorilla-Selim duet; with the languising lightness and wonderful legato of the Caterina Cornaro aria, here in one of Gencer’s most beautiful performances; with the new proposal of the aria from Paisiello’s Molinara, with its enchanting introspective tone and delicate variations and the whispered complicity of “A mezzanotte” Almost as if to seal a last intimate appointment with her beloved Donizetti and with her adoric public, electrified by an eternally fascinating artist, whose magic still remains impenetrable and overpowering even for those listening to this recording.