1 9 9 6

Il simbolo della cultura dimenticata

Pavorotti: Finita un’epoca

Milano - Si chiude un' epoca, dice chi lo conosceva, chi gli era stato vicino in teatro. Ma per gli amici, per gli artisti che gli si erano affezionati indelebilmente, Gianandrea Gavazzeni era un grande uomo e un artista ricco di cultura e umanità. Così il mondo della lirica lo ricorda unanimemente. Con il dolore che si prova di fronte alle grandi perdite dice Riccardo Muti: "Gavazzeni è stato per tutti noi musicisti una figura autorevole e un uomo generoso nel consigliarci". E Luciano Pavarotti: "Era il simbolo di una generazione di meravigliosi musicisti. Con lui si chiude l' epoca del belcanto che ora non ha più protagonisti. Era così bello ascoltarlo durante le prove. Non so più nemmeno io quanti Verdi ho fatto con lui, quanti Rigoletto. Con Verdi, io dicevo sempre che lui ci faceva fare le ' frasi alla Gavazzeni' , perché aveva portato le frasi larghe, cogliendo l' esuberanza, la potenza verdiana". Affranti due grandi amici, Leyla Gencer e Carlo Bergonzi che con Gavazzeni hanno condiviso 40 anni di carriera e di vita. Il soprano: "Prima La Fenice, ora il maestro. Per me erano intimamente legati. Con Gavazzeni ho fatto le cose più importanti. Di lui era sorprendente la capacità di essere profondo e brillante. Una delle ultime volte che ci vedemmo, mi regalò ' Le affinità elettive' di Goethe, con una dedica, come faceva sempre". E Bergonzi: "Dopo Karajan, Serafin, Votto, c' era lui. Se ne va un' epoca. Io l' adoravo e lui aveva un' adorazione per me, diceva che solo io potevo cantare ' Si schiude in ciel' dall' ultimo atto dell' Aida". Con Gavazzeni se ne va "un mondo culturale e musicale che, prima ancora che sull' arte ha basato le sue fondamenta su straordinari valori umani" ha ricordato Carlo Fontana, sovrintendente scaligero "per la Scala dove ha diretto per più di 50 anni, ha rappresentato la memoria storica". Commosse Renata Tebaldi che oggi ricorda "la simpatia, la giovialità e la grande cultura" e Mirella Freni che conobbe Gavazzeni nel 1963, alla Scala per L' amico Fritz di Mascagni e che avrebbe cantato nella Fedora scaligera del prossimo marzo: "Abbiamo lavorato insieme soprattutto in questo ultimo periodo. Nel repertorio verista mi ha insegnato tutto". Il soprano Rajna Kabaiwanska, aveva esordito nel mondo della lirica proprio con Gavazzeni: "Mi ha cresciuta lui. Era rimasto l' ultimo direttore a intendere la musica come una schiavitù nobile, come appartenenza totale del direttore al suo pubblico. La musica significava per lui soprattutto un modo per trasmettere emozioni ed io sono cresciuta con questo credo". Carla Fracci confessa che "con Gavazzeni se ne va una grande parte della mia giovinezza. Era il lume di cui si ha bisogno per non sbagliare nel cammino". (anna bandettini) o cresciuta con questo credo". Carla Fracci confessa che "con Gavazzeni se ne va una grande parte della mia giovinezza. Era il lume di cui si ha bisogno per non sbagliare nel cammino".

LA REPUBBLICA

La mia priora per Gavazzeni'

Verona - "Sono andata avanti per forza d' inerzia.

Non avrei voluto: l' ho fatto soltanto per rispettare la sua volontà".

Denia Mazzola Gavazzeni, all' indomani del debutto al Teatro Filarmonico nei

Dialoghi delle Carmelitane di Poulenc, opera che avrebbe dovuto segnare anche

l' ennesimo esordio artistico per Gianandrea Gavazzeni: "Aveva sempre

detto, gli impegni si onorano fino in fondo e i fatti personali non devono

interferire. L' ho fatto anche in segno di affetto e di riconoscenza verso il

teatro, i collaboratori e i colleghi". Il teatro non si ferma, ricordava

l' appassionata prestazione della Mazzola nei panni di Madame Lidoine - parte

che fu di Leyla Gencer nella prima assoluta alla Scala (26 gennaio 1957) -

"la più spirituale dell' opera. La nuova Priora è la vera guida per tutte:

l' ultimo arioso avrei tanto voluto cantarlo per lui. A lui l' ho dedicato. Ma

sentivo che erano in molti a far musica come se fosse presente, l' altra

sera". Gavazzeni non aveva mai diretto Les Dialogues pur amandola molto.

Di certo l' avrebbe fatto offrendosi con la consueta profondità di sentire la

drammaticità delle parole e l' inquietudine dell' esser religioso arso dai

dubbi e indirizzato alla professione individualistica. "Il maestro era

affascinato, oltre che dalla musica dal centro espressivo dell' opera",

ricorda ancora la moglie: "quel continuo discutere sulle ragioni della

vita e della morte fin dalle prime scene, che poi cresce progressivamente pur

senza diventare freddo teologismo, mantenendo anzi una dolorosissima carica

umana. E aveva un' autentica venerazione per il grandioso e terribile ' Salve

Regina' che conclude l' opera (lo intonano le sedici carmelitane mentre salgono

verso la ghigliottina; a ogni testa che cade, una voce si spegne, ndr), una

pagina bellissima e densa: ' questo Salve Regina è la scala per il Paradiso' ,

diceva spesso. Anche per me ha un significato particolare: è l' ultima musica

che gli ho cantato, pochi giorni prima della morte". Gavazzeni che ai

Dialoghi aveva dedicato alcune pagine diaristiche leggibili nella raccolta Il

sipario rosso conosceva anche molto bene l' autore, con il quale "aveva

avuto molte occasioni di incontro. Di Poulenc parlava come un uomo mite, un

pianista brillante e una personalità coltissima. In occasione della nascita dei

Dialoghi ne ricordava la dolcezza e l' incapacità di entrare in conflitto con

le logiche non sempre civili d' una rappresentazione teatrale così complessa e

accompagnata da varie tensioni: prima assoluta, produzione difficile - la

migliore regia della Wallmann, diceva sempre - compagnia di primedonne. Ci

furono molte occasioni di scontro: l' autore non si ribellò né perse mai la

pazienza". Al Filarmonico veronese c' era molta commozione, un clima

intenso a una settimana dalla morte del maestro. Pertinente al carattere

plumbeamente potenziale e celebrativo del martirio cattolico che dà spessore

drammatico all' opera. D' alto livello la qualità esecutiva (molto efficace la

distribuzione vocale con Danielle Streiff ottima protagonista e Anna Schiatti,

Diane Curry, Darina Takova, Antonella Trevisan, Diego D' Auria, Jorge Perdigon

e Alessandro Corbelli) e la classe dell' allestimento Grossi-Fassini importato

dall' Opera di Roma. Per un non meno significativo passaggio di testimone la

guida musicale fervida era di Roberto Tolomelli, scelto a suo tempo da

Gavazzeni come assistente e promosso al primo podio.

Solo peccato veniale da splendido sessantenne

LA REPUBBLICA

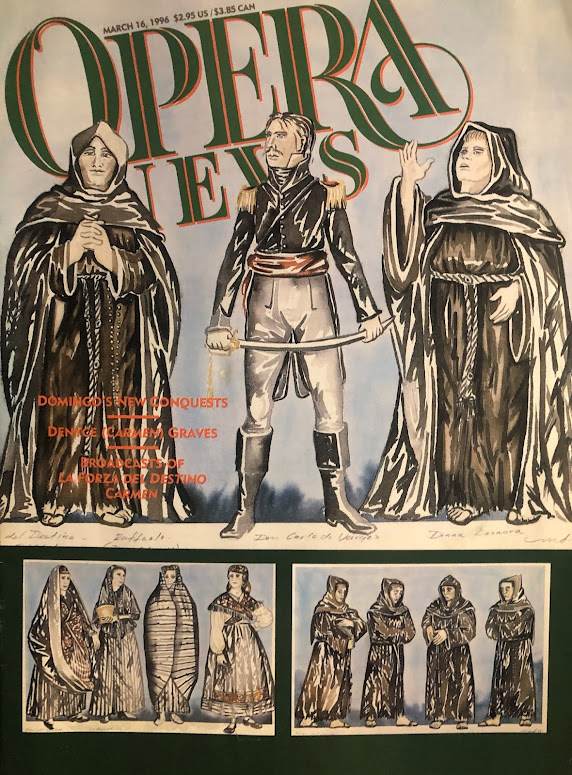

Pizzi: 'Il mio Macbeth scende nell’Arena

Verona - "Se Macbeth è l' opera dello smarrimento,

della fatale solitudine e della notte invocata come complice, nessuno spazio è

più adatto a evocarla della gigantesca volta del cielo spalancata dal catino

dell' Arena". Parola di Pier Luigi Pizzi, autore dell' attesa messa in

scena del Macbeth di Verdi che inaugura venerdì sera il 75esimo Festival

areniano. Forte di una lunga confidenza con il capolavoro, affrontato per la

prima volta come scenografo nel 1969 (per la regia di Giorgio De Lullo all'

Opera di Roma: protagonista era Leyla Gencer) e di una militanza

anticonformista degli spalti areniani già ridisegnati per 'Turandot' (1969) e

'Carmen' (1970), Pier Luigi Pizzi non crede al luogo comune delle opere

'areniane' . Anzi: "Dal mio punto di vista non potrei mai fare qui 'Aida'

, che ritengo partitura intima come nessun' altra", confessa il regista

che sta già montando l' 'Attila' che debutterà al Teatro Alighieri di Ravenna

il 21 prossimo, "mentre mi appassiona l' idea di tradurre la claustrofobia

di Macbeth in una sorta di fredda agorafobia, con i destini dei due

protagonisti 'mossi' sempre dalle streghe (il coro e alcuni mimi insieme) ma

schiacciati dall' immenso firmamento". La scena creata da Pizzi sviluppa

lungo l' asse orizzontale "uno spettacolo tutto proiettato verso il

pubblico", mentre le gradinate dietro il palcoscenico rimarranno deserte.

Unico colpo di scena, l' apparizione del castello di Macbeth: "Salirà dal

nulla, come per un sinistro incantesimo, e avrà l' aspetto di una gigantesca trappola,

un' insidiosa esca per Duncano, vittima designata". E' solo la terza

volta, dopo il 1971 e il 1982, che il capolavoro giovanile verdiano (titolo

scelto, nella versione originale del 1847 anche per aprire il Festival di

Martina Franca, tra venti giorni) approda in Arena. Lo fa con la veste delle

grandi occasioni: spettacolo annunciato avvincente, coppia protagonistica di

richiamo e collaudata (Maria Guleghina e Paolo Gavanelli) con Carlo Colombara e

Giorgio Merighi a completare la prima distribuzione, Carla Fracci ("una

sorta di doppio di Lady Macbeth") interprete della danze e John Neschling

sul podio delle otto recite, fino al 26 agosto. Secondo titolo, Madama

Butterfly, altro nuovo allestimento in prima da sabato (mentre domenica rinasce

per l' ennesimo anno Aida nella versione storica 1913, diretta da Nello Santi).

Debutto in casa per il veronese Beni Montresor, anche lui autore di regia,

scene e costumi. Lo spettacolo, dedicato a Raina Kabaivanska che sarà Cio-Cio

San per l' ultima volta, ha nove repliche (fino al 29 agosto) e sarà diretto da

Angelo Campori: Francesca Franci è Suzuki, Keith Olsen Pinkerton, Giorgio

Zancanaro Sharpless. Anche in questo caso, l' allestimento non cerca

monumentalità estranee alla musica e lascia respirare i marmi areniani. Scenografia

di base, oltre al bianco accecante rituale colore giapponese di morte, saranno

le luci che Montresor ha voluto moltiplicare attraverso un gioco di specchi che

investe i controllati gesti del personaggio della popolare tragedia giapponese.

1 9 9 8

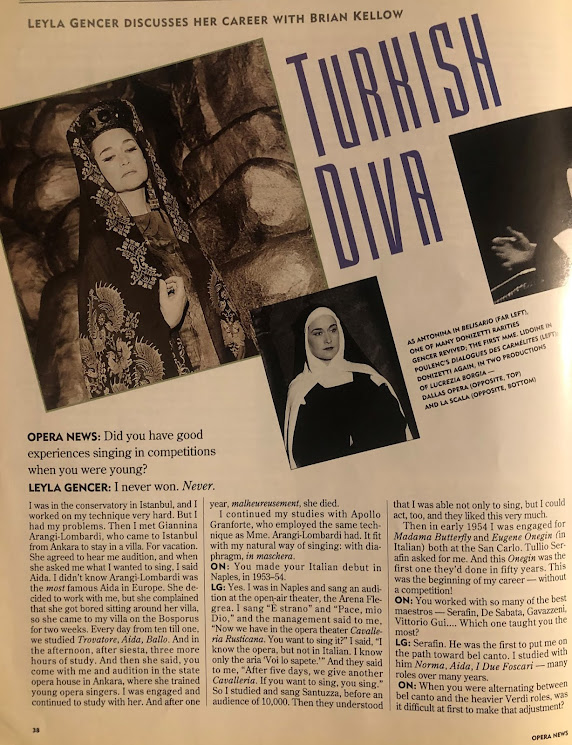

Intervista a Leyla Gencer per Opera International (No. Settembre 1998) (ruccolta de Franca Cella)

Versione originale (senza .......!)

Intervista A Leyla Gencer

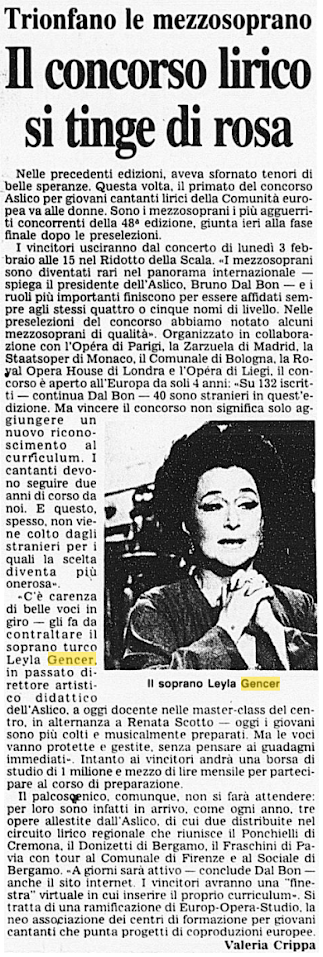

1797-1848, 200. Anni fa nascava, 150 anni fa moriva Gaetano Donizetti. Due stagioni di anniversari ravvicinati hanne stimoleto un panorama internazionale di esecuzieni, risceperte, conbegni, mostre, rapportie con un compositore acclamanto dai suoi centemporanci, poi ridinensienate a pochi titoli trainvanti, e recuperate oggi cen 56 opere, sulla 70 compostia.

Ne parliano com Leyla Gencer, interprete pilota della rinascita donizettiana degli anni 1960-1970, con le sue riscerparte di regine ed eroine, la carica di sucesso popolare restitaite a Donizetti, la ricerca di una verita donizettiana preseguita sensa sesta. 11 opere di impatta olamerese, subito multiplicate della represe ne grandi teatri, dall’Italia a Edinburgı a New York, a della diffusione caprillare di registratizioni live a CD; liriche da camera prefuse con seduzione nei suoi concerti, a fervere di docente, attualmente in oarica all’Accademia di perfezionamente del Teatro alla Scala.

Il feeling che ci attira a Donizetti?

La sua sensibilita moderna al momento psicologia. Forse la malattia gli dava la capacita di capire che cosa di profondo e quanti cambiamenti puo subire la mente umana, a seconda delle vicende, dei traumi che subisce. Nelle sue pazzie c’e assolutamente questa forza drammatica di cambiamenti repentini, improvissi,

GAZETTA MATOVA

Casa Verdi anche per giovani musicisti

Milano - La casa di riposo per musicisti`Fondazione Giuseppe Verdi' di Milanoospiterà dal `99 anche giovani studenti meritevolie bisognosi. "La Fondazione - ha detto ilpresidente Antonio Magnocavallo - ha procedutoad una riforma dello statuto: dal `99 CasaVerdi ospiterà anche studenti di musica di Conservatorio,Civica e Accademia della Scala, scelticon criteri di merito e disagio. Si cominceràda 2 a 4 ma sempre con la precedenza agli anzianimusicisti". A festeggiare la novità (proprioil 10 ottobre di 185 anni fa nacque GiuseppeVerdi), un vero e proprio `parterre de roi':da Saverio Borrelli a Giuseppe Di Stefano, Leyla Gencer, Giulietta Simionato, Magda Olivero.In 100 anni `Casa Verdi' ha ospitato piùdi 5000 anziani musicisti. Oggi gli ospiti sono60. Le stanze dopo la ristrutturazione saranno72. L'idea di aprire ai giovani è piaciuta ancheai grandi direttori Muti, Chailly, Abbado.

1 9 9 9

LA REPUBBLICA

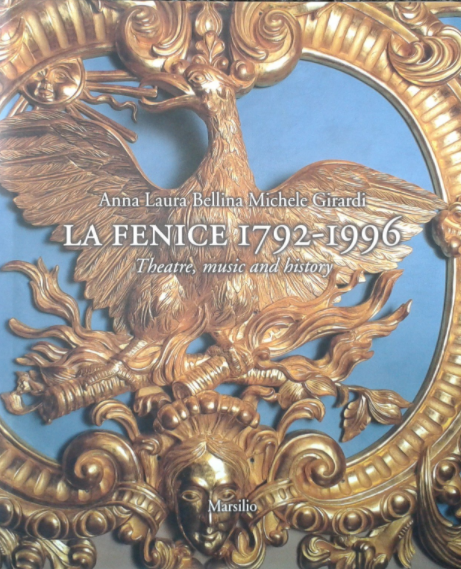

Tre anni dal rogo, la Fenice non rinasce

Venezia - C' era un taglio di luna, e un' aria secca,

quasi ferma, quella sera. Un cielo pulito che si vestì di fuoco e colorò di

rosso, non erano neanche le nove, quando la Fenice bruciò, prima il tetto, poi

tutta, si consumò in meno di una notte, come una scatola di fiammiferi. Era il

29 gennaio del 1996, sono passati tre anni, il suo scheletro è ancora lì,

dentro una gabbia di tubi, ferme le gru, chiuso il cantiere, monumento alla

vergogna. Ricorsi, denunce, tribunali, tutto bloccato, nessuno che sa dire quando

i lavori ricominceranno, nessuno che osa dire quando Venezia riavrà la Fenice.

Se la riavrà. E il mondo che aveva pianto, che si era mosso, che aveva mandato

soldi (6 miliardi), e altri 8 ne aveva messi a disposizione su conti esteri,

adesso s' indigna. Negli uffici del teatro, box piantati attorno al tendone del

Palafenice nello squallore dell' isola-parcheggio del Tronchetto, piovono

messaggi di rabbia e di dolore, da ogni parte, nel terzo anniversario dell'

incendio. E' domani. Una ricorrenza mesta, senza discorsi, senza celebrazioni,

senza più promesse. Solo una trasmissione alla radio, la mattina (RadioTre) e

un concerto gratuito, la sera, nella chiesa di S. Stefano, organizzato dai

lavoratori del teatro, che usano parole come "impotenza, preoccupazione,

scetticismo, disattenzione, disagio", perché le prospettive di una

riapertura "si allontanano". "Venezia senza teatro, senza

teatri, è gravemente ferita, priva di memoria, di festa, di fantasia" dice

il regista Maurizio Scaparro, che sente "tornare l' amarezza, l' emozione,

la frustrazione". I messaggi alla Fenice, a tre anni dal rogo, piovono via

internet, via fax, via posta. E se c' è ancora, nonostante tutto, speranza,

nelle parole dei grandi nomi, come Leila Gencer, Dee Dee Bridgewater ("spero

tanto di tornare a cantare nel teatro dove, prima di me, si sono esibiti Ella

Fitzgerald e Ray Charles"), c' è solo sdegno e amarezza in quelli del

popolo del loggione. "Dov' era, com' era, e dove non sarà mai ?" si

chiede Michele Girardi, musicologo di Parma, che accomuna "la colpa

atroce" di chi ha appiccato l' incendio a quella di chi "ne ostacola

la ricostruzione". Una "decisione sconcertante" quella di

sospendere i lavori, per Luca Garau, di Varese, che accusa la commissione prefettizia:

"Con un bando di quel genere il gioco di corsi e ricorsi e ricorsi ancora,

non era solo un rischio ma una certezza". Ma ce n' è anche per i veneziani

"che sono sempre stati inarrivabili per baloccarsi con le parole"

scrive Daria Mazzurana da Milano, e per i politici: "Signor Sindaco,

Signor Prefetto, Signori Ministri - chiede Giulia Perocco - quando potremo dire

di nuovo "è" e non "era" della Fenice? Da qualche mese ho

scoperto che dico "era", vuol dire che il teatro sta diventando il

passato, un pezzo morto, un brandello della memoria...". "E'

umiliante - accusa Alvise Zanchi, veneziano, trentun anni e "nessuna

fiducia di rivedere un' opera nel mio teatro" - ed è difficile non

sentirsi traditi, orfani, feriti, e non scoprire in una luce sinistra, come dei

personaggi da farsa amara, i politici e i responsabili che omettono di esporsi

e di pronunciarsi con forza per sbloccare la situazione". "Stupidità,

ignominia, incapacità" accusa Gabriele Visentini che se la prende con gli

appalti chiamati "trasparenti" e invece "gestiti sempre alla

stessa maniera" e con gli amministratori responsabili che si dimostrano,

viceversa, "irresponsabili". C' è anche chi manda un racconto, come

Giolonardo Dell' Arpa, musicista, che scrive di "un ragazzino che rivuole

il suo sogno": "a lui non frega nulla dei soldi, della burocrazia,

delle leggi e degli imbrogli: lui vuole di nuovo il suo luogo del sogno,

rivuole il suo teatro". E c' è chi, più pragmaticamente, come la contessa

Barbara Valmarana, manda un appello al ministro Melandri: "Ci aiuti, e

aiuti i veneziani a riavere il loro teatro". Ma c' è anche chi, come

Pierfranco Moliterni, docente all' università di Bari, chiede di non

dimenticare il Petruzzelli, per far sì che "con l' aiuto di tutti e senza

l' indifferenza di alcuno" risorga anche "il teatro dei

pugliesi". Dall' America, dalla Francia, dall' Australia arrivano anche

auguri e messaggi di speranza. "Fortuna e successo per la

ricostruzione" scrive Claudia Meuli da Costanza, "Aspettiamo la

riapertura con grande impazienza" dicono dall' associazione "Art et

Fugue" di Ginevra, "che il teatro mi aspetti" digita Maura

Termite da Milano, e Enrico Balli da Torino scrive venti volte la parola

"solidarietà". E' una pioggia di messaggi. Roberto da Pavia, Claudio

da Milano, Simone da Lucca, Francesco da Vicenza, Carlo da Torino, Cristiano da

Ferrara, Alberto da Udine, Richard da Pistoia... perché, come scrive Leonardo,

da Arezzo, "una storia così non può finire... stringete i denti!".

2 0 0 0

GIUSEPPE VERDI L’UOMO, L’OPERA,

IL MITO

Carlo Fontana mi propone una grande esposizione in occasione del primo centenario della morte di Giuseppe Verdi, innovembre, al Palazzo Reale di Milano. Grazie della fiducia, ma devo pensarci su. Si fa presto a dire Verdi. "Va pensiero".Viva V.E.R.D.I. Non si sa da che parte cominciare. Ci sono — mi dice — fonti inesauribili di materiale fra il Museo delTeatro alla Scala e l'Archivio di Casa Ricordi.Ho paura che si tratti essenzialmente di una mostra cartacea, senz'anima: lettere, libretti, spartiti, fogli autografi, bozzettidi scena, figurini di costumi. Carta. Dov'è il grande impatto visivo? Dov'è l'emozione? Penso che sarebbe meglio cherinunciassi, perché ho passato troppi anni della mia carriera in trincea a battermi con tutta la passione della fede che lamusica di Verdi ha fatto nascere in me per rassegnarmi ad abbassare le armi proprio adesso. Non posso fare a Verdi questotorto; gli devo troppi momenti di vera commozione, così rari in chi si è indurito in tanti anni di mestiere. Mi basta pensare aun "Libera me, Domine" intonato da Leyla Gencer a Massenzio in una notte d'estate tanti anni fa: nel pensare questamostra devo ritrovare questo tipo di emozione. Bisogna mettersi al lavoro con animo puro: tornare a Busseto, a VillaSant'Agata, sentire Verdi vivo.Spiego tutto questo a Carlo Fontana, a Francesco Degrada, a Pierluigi Petrobelli, a Gabriele Dotto, lo racconto a RiccardoMuti. Sono tutti d'accordo, per fortuna: non solo carta, dunque, non solo documenti, ma immagini di vita e di lavoroevocate attraverso i luoghi veri e le opere, nel clima che le ha ispirate. Perciò ci devono essere la casa natale di Roncole e lacamera a Villa Sant'Agata, per la cui ricostruzione dovrò coinvolgere i Carrara Verdi, ottenerne la fiducia e lacomprensione. Si devono raccontare per immagini i mondi nei quali Verdi è stato da subito protagonista, dal Teatro allaScala dei suoi esordi clamorosi ai salotti milanesi degli incontri determinanti, da Manzoni a Francesco Hayez, la cui pitturastorica tanto ha nutrito la sua cultura figurativa. Bisogna raccontare la sua influenza sull'editoria musicale, illustrare il suoimpegno politico e sociale, da cui nasce con gesto generoso la Casa di Riposo per Musicisti. Forse si dovrebbe riuscire araccogliere i resti sparsi della stanza dell'Hótel de Milan, per ritrovare il silenzio profondo e la solitudine del momento in cuiil grande Maestro si è spento.Poi si deve affrontare il suo monumentale lavoro. Tutte indistintamente le sue opere devono essere documentate condisegni di scene e costumi. Posso contare per questo sulla infallibilità di Mercedes Viale Ferrero e la complicità di VittoriaCrespi Morbio. Con Degrada e Petrobelli abbiamo già deciso di dare spazio alle fonti letterarie, perché tutti capiscano cheVerdi possedeva una solida cultura, per niente provinciale, e un senso assoluto del teatro, che faceva di lui un registaconsapevole. Bisogna che la sua biblioteca sia presente, almeno in parte, nel percorso della mostra. Siccome sono uomo diteatro, non resisto alla tentazione di ricostituire una delle scene più spettacolari: il trionfo di Aida, che penso di evocaremolto liberamente a partire dal bozzetto e dai costumi di Magnani per la prima rappresentazione alla Scala nel 1872. Mabisogna mettersi subito al lavoro: non c'è un minuto da perdere. Ho già dei compagni di cordata: gli architetti FrancescoMuti e Luca Rolla, Gigi Saccomandi e Giovanna Buzzi; e mi rassicura che tutto sia tenuto sotto controllo da RobertaCavallini. Per celebrare il mito di Verdi penso a una ricostruzione in scala ridotta — partendo dai venti bozzetti superstiti di Ximenes, che rappresentano altrettanti personaggi verdiani — del monumento che la città di Parma dedicò nel 1913 allamemoria del Maestro, e che la guerra e l'insensibilità civile hanno cancellato.Questa sintesi evocativa dell'opera di Verdi dovrebbe, spero, lasciare in chiusura un segno al visitatore: ricordare ad ognunoquale immenso patrimonio d'amore questo grande uomo ci ha lasciato in eredità, per sempre.

2 0

0 1

I VIP della lirica racontano ecco a voi “Il Mio Verdi”

Da Muti a Liliana Cavani a ciascuno il suo Verdi

Il baritono Leo Nucci parla del sentimento di dolore espresso nel coro degli ebrei del Nabucco. Il regista Jonathan Miller spiega la sua interpretazione provocatoria del Rigoletto, dove il gobbo diventa un barista losco, sciancato e mafioso. Luca Ronconi racconta il suo stretto rapporto col Trovatore, opera poeticamente densa e complessa. Riccardo Muti esprime la sua felicità nel dirigere il Faslstaff. Sono solo alcune delle testimonianze raccolte dalla gioornalista Leonetta Bentivoglio nel libro Il mio Verdi (Socrates edizioni) presentato ieri alla Scala. La parola non è data ai musicologi o ai critici, ma a sedici tra interpreti, registi, direttori che hanno portato in scena i dodici più grandi capolavori del compositore di Busseto: da Macbeth (Renato Bruson e Leyla Gencer) a Traviata (Liliana Cavani e Zubin Meta), dal Ballo in maschera (Luciano Pavarotti) alla Forza del destino (Giuseppe Sinopoli), dal Don Carlo (Myungwhun Chung), ad Aida (Riccardo Chailly e Franco Zeffirelli), da Simon Boccanegra (Claudio Abbado e Mirella Freni) a Otello (Peter Stein). La prefazione è di Carlo Fontana, le schede delle opere di Angelo Foletto. La presentazione è stata l' occasione per affrontare il tema della qualità delle voci verdiane attuali. Fontana ha difeso i cantanti di oggi: «Certo ci sono vocalità meno ricche, ma l' arte dell' interpretazione è legata al proprio tempo. Tanti cantanti del passato oggi sarebbero inadeguati: se sul palco della Scala ci fosse ora Beniamino Gigli, succederebbe il finimondo. Bisognerebbe avere il coraggio di rompere in libertà con la tradizione. Dobbiamo guardare il presente con gli occhi del presente».

LA REPUBBLICA

Verdi visto dai suoi interpreti. Il prossimo 27 gennaio si compiranno cento anni dalla scomparsa di Giuseppe Verdi. La vita musicale nel 2001 sarà dominata inevitabilmente da miriadi di celebrazioni di questa ricorrenza lasciando ben poco spazio ad altre iniziative che pur si imporrebbero, come, ad esempio, la celebrazione del bicentenario della nascita di Vincenzo Bellini. Il Ministero per i Beni e le Attività culturali ha provveduto con largo, opportuno anticipo, a costituire un Comitato Nazionale per le Celebrazioni Verdiane che svolge un encomiabile lavoro di promozione e di coordinamento delle manifestazioni programmate in Italia. Un Verdi Festival diretto da Bruno Cagli verrà inaugurato il 27 gennaio nel Duomo di Parma, alla presenza del Presidente Ciampi e del Ministro Melandri, con l’esecuzione del Requiem di Verdi diretto da Valery Gergiev e nello stesso giorno, nel piccolo Teatro Verdi di Busseto, andrà in scena un’Aida intimistica con la regia di Zeffirelli. Tra il 27 gennaio e il 1 febbraio un Convegno Internazionale di Studi «Verdi 2001» si svolgerà a Parma per proseguire presso la New York University e la Yale University di New Haven. Gli Enti lirici e le consimili istituzioni italiane non hanno però atteso la fine di gennaio. Il Carlo Felice di Genova ha aperto la stagione 2000/2001 con un’edizione in lingua francese di Jérusalem. La Scala ha puntato sul Trovatore. Ed è quest’ultimo spettacolo che ha suscitato la più larga messe di critiche e articoli di ogni genere. Nella maggior parte di questi scritti uno spazio invero eccessivo appare dedicato alla questione se Riccardo Muti aveva fatto bene o male di seguire alla lettera la partitura di Verdi e di vietare al tenore di cantare il catartico Do nell’Aria Di quella pira, consacrato dalla tradizione, ma non richiesto dall’autore. Bisogna sperare che il maxiconvegno parmenseamericano rechi un contributo davvero sostanzioso sull’approfondimento delle conoscenze circa la personalità e l’arte del più celebrato tra i compositori italiani. Lo dovrebbe far sperare il fatto che a quel convegno è stata invitata la crema degli studiosi verdiani di tutto il mondo. Non vi figura però nessun direttore d’orchestra, nessun regista, nessun cantante. Cioè nessun interprete. Nessuno di quegli artefici che soli possono far sì che l’esecuzione di un’opera assuma valore di un’epifania o di una risurrezione. Appare dunque quanto mai attuale e opportuna la pubblicazione di un libro come quello in cui, sotto il titolo Il mio Verdi, Leonetta Bentivoglio fa parlare sedici dei più grandi interpreti verdiani del nostro tempo delle opere di Verdi da essi più intensamente rivissute (Edizioni Socrates, pagg. 176, lire 28.000). L’idea di questo piccolo, ma prezioso volume, nasce da una serie di quattro interviste scritte per la Repubblica nell’estate del 2000 (con Zubin Mehta per La Traviata, Luciano Pavarotti per Un ballo in maschera, Riccardo Muti per Falstaff e Jonathan Miller per Rigoletto) alle quali sono state aggiunte dodici conversazioni: con i cantanti Leo Nucci, Renato Bruson, Leyla Gencer e Mirella Freni; con i direttori Giuseppe Sinopoli, MyungWhun Chung, Riccardo Chailly e Claudio Abbado; con i registi Luca Ronconi, Liliana Cavani, Franco Zeffirelli e Peter Stein. Modestamente l’autrice parla di «una uniforme esposizione di stile divulgativo e giornalistico, senza pretese saggistiche o musicologiche». Bisogna dire però che non poche pagine rivestono invece un autentico interesse musicologico. Così, ad esempio, quelle in cui Riccardo Chailly rivendica e precisa i veri e propri prestiti che Mahler mutuò dal Falstaff e soprattutto dall’Aida. O quelle in cui Sinopoli collega aspetti di La forza del destino ad esperienze di compositori che vanno da Musorgskij a Nono. Di sorprendente interesse le risposte di cantanti colti e consapevoli come la Gencer e Nucci. Quest’ultimo riferisce l’impressionante episodio avvenuto a Tel Aviv, nel 1994, quando il pubblico che assisteva alla prima rappresentazione del Nabucco in Israele, alle parole “Torna Israello, torna alle gioie del patrio suol”, si alzò in piedi «per applaudire e urlare». Quasi a dimostrare che l’opera non ha nessun bisogno di essere «attualizzata» mediante le famigerate «trasposizioni d’epoca» come quella per cui Miller ambientò il Rigoletto nell’ambiente della mafia italoamericana di Coney Island. E nella sua intervista Miller ci promette ancora: «... nel 2001, a Torino, farò un Macbeth ambientato in Kosovo. Nel ruolo del titolo ci sarà Arkan, il macellaio di Milosevic, capo del famigerato gruppo delle “tigri” serbe. Era sposato con una cantante, tale Zeza... Sarà lei la mia Lady Macbeth». Non so davvero come si possa giustificare una simile concezione che obbliga l’orecchio a percepire una musica dell’Ottocento, mentre l’occhio deve guardare immagini del 2000. Con la conseguente distruzione schizofrenica di qualsiasi parvenza di unità dell’opera rappresentata. Per fortuna ci sono anche registi che rispettano maggiormente le intenzioni dei compositori. Un confortante esempio ce lo offre in questo contesto Peter Stein il quale, prima di mettere in scena l’Otello, confessa di aver studiato le indicazioni dello stesso Verdi, pubblicate nel volume La disposizione scenica con «una descrizione minuziosissima della messa in scena così come la voleva il compositore, con i disegni dei costumi e l’organizzazione del palcoscenico». L’interesse del volume è accresciuto da lucide ed equilibrate schede e da un’ampia discografia di Angelo Foletto. La prefazione di Carlo Fontana testimonia dell’ormai superata contrapposizione WagnerVerdi e conclude con la constatazione pienamente condivisibile: «Questo libro contribuisce intelligentemente alla riflessione sull’opera di Verdi».

LA REPUBBLICA

«La mia prima volta nel loggione la trascorsi una sera del 1948, avevo otto anni e mi ci portò mio nonno, grande appassionato di lirica. Da allora non ho più smesso di andarci». Adriano Oliva, sessantun anni, milanese, fresco pensionato (era dirigente in un grande gruppo assicurativo), fa parte del nucleo storico dei loggionisti, frequentatori assidui da decenni, intenditori raffinati e agguerriti sostenitori di quello che Fontana ha definito «un reperto archeologico». Che cosa risponde a questa affermazione del sovrintendente? «Reperto archeologico? Ma per piacere. Lui non vuole capire la vitalità del loggione, i suoi contenuti. E non gli sembra un reperto archeologico, un retaggio feudale, il meccanismo degli abbonamenti, diciamo così, ereditari? Da generazioni se li passano le stesse famiglie, e non permettono l' accesso a nessun altro, a nessun elemento nuovo. Gli sembra bello? E poi, davvero, non tiene conto di quanta cultura e amore per la lirica ci siano nel nostro gruppo». Come si diventa loggionisti? «Per passione. Io, le dicevo, quella sera del '48 ero un bambino, e mi feci un sonno profondo. Ma poi mio nonno mi portò ancora, e fui affascinato da quel teatro così scintillante. Qualche anno dopo (studiavo al Berchet) cominciai ad andarci per conto mio, e divenni un habitué. Il biglietto costava 125 lire. Non poche, per uno studente, ma quella sala tutta oro e velluto, con quel fascino particolare, mi rapiva. Non mi perdevo un' opera, anche le più inconsuete. A quei tempi in una stagione c' erano fino a 25 titoli, più il balletto. La domenica c' erano due spettacoli: me li vedevo tutti e due». E si metteva in coda «Certo. Non era come adesso. Erano code vere, si restava lì ammassati, finché toglievano le catene e ci si precipitava dentro, e giù spintoni, pestate di piedi~ All' inizio ci facevano stare all' interno del teatro, c' era uno sportello al piano di sopra e la coda scendeva per lo scalone. Ogni tanto c' erano i soliti furbi, arrivavano per ultimi e cercavano di confondersi tra i primi». E una volta entrati, com' era l' atmosfera? «Magica. Elettrizzante. Non c' erano le poltroncine, ma le panche di legno, e si finiva per salirci tutti in piedi per vedere, sentire, fare il tifo, accalorarsi. Certo, avevamo nomi come Callas, Tebaldi, Del Monaco, Di Stefano, Corelli, per citarne solo qualcuno. C' era l' imbarazzo della scelta tra i migliori. Io, per non sbagliare, andavo a sentirli tutti. Ero studente, liceo classico, mi interessava la cultura in genere, e mi piaceva discutere con gli altri». Il "suo" gruppo è sempre stato affiatato «Altro che. Durante le code, e poi negli intervalli, si discuteva di tutto, arte, musica, letteratura. Dopo si continuava a parlare fuori, in strada, al massimo si beveva un bicchiere da Scoffone, d' estate si prendeva l' anguria o la granita ai chioschi di piazza Castello. Nascevano affinità e simpatie, grandi amicizie, anche l' amore: ci sono state coppie che si sono sposate, e continuano a venire in loggione». Ha fatto conoscenze speciali? «Persone di grande preparazione, vecchie e giovani. Artisti: come Rajna Kabaiwanska, che studiava a Milano, o Alberto Cupido, che da studente faceva parte della claque per guadagnare qualcosa, o il compianto maestro Dino Ciani. E poi tanti melomani di altre città, e stranieri. Compresi i "transistor", cioè i giapponesi, li chiamavamo così perché avevano un sacco di apparecchi. Noi li accompagnavamo di qua e di là, e magari li ospitavamo quando venivano per uno spettacolo. E poi, se andavamo in trasferta per assistere a opere in teatri italiani o stranieri venivamo ospitati a nostra volta.. I soldi non giravano tanto, né quando ero studente né da militare. Ecco, il periodo della leva è stato l' unico in cui mi sono perso un 7 dicembre. In compenso, ho trascinato un po' di commilitoni alla Scala, gente che non aveva mai messo piede in un teatro, e si sono entusiasmati. Andammo a Parigi a sentire la Callas, che a Milano non veniva più; a Palermo per una rara Elisabetta regina d' Inghilterra; a Firenze per Muti, che era entusiasta e straordinario. Visitavamo musei e mostre. E a teatro spesso non pagavamo, grazie all' amicizia con artisti conosciuti in loggione: una volta, a Brescia, il teatro era esaurito, ma la Gencer e la Cossotto, nostre amiche, costrinsero la direzione a farci entrare. A Milano frequentavamo i luoghi della prosa, il Piccolo di Grassi e di Strehler. Non si può dire che siamo fruitori superficiali, come vede». Ci sono fra voi dei personaggi di riferimento? «Ci sono sempre stati. Noi eravamo un gruppo di giovani, ma la nostra migliore amica era la Rina, la famosa Rina Falcetti, che aveva settant' anni ed era acerrima nemica della Callas. Adesso c' è Luisa Mandelli, detta Annina perché era una cantante ed ebbe quel ruolo in Traviata accanto alla Callas. Durante gli intervalli, la gente va da lei a fare commenti su opera e artisti. Si commenta sempre, tra noi, e a volte in modo accanito, ma sempre mantenendo il senso del divertimento. Ridimensionerei il mito che ci descrive come fischiatori e contestatori: sì, siamo palati raffinati e cerchiamo il meglio, cogliamo le calate di tono dei nuovi artisti, a volte anche di quelli affermati, ma non siamo dei maleducati. Fontana dice che abbiamo rovinato il Ballo in Maschera, a maggio: ma dovrebbe sapere che gli insulti alla Guleghina sono partiti dai palchi, non da noi».

THE SAN FRANCISCO EXAMINER

2 0 0 2

2 0 0 3

2 0 0 4

INNER VOICE Renée Fleming on her La Scala Borgia

IL PICCOLO

Omaggio al principe Cappuccilli

Milano. A quarant'anni esatti dal suo debutto scaligero, avvenuto il 12 giugno 1964 in un memorabile allestimento di Lucia di Lammermoor, Piero Cappuccilli torna a Milano per ricevere l'omaggio dei suoi amici e colleghi più cari: sabato 19 giugno, alle 21, una grande festa vedrà radunati all'Auditorium di via Mahler alcuni protagonisti del melodramma internazionale. L'Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano Giuseppe Verdi sarà diretta da Romano Gandolfi. La serata, condotta da Antonio Lubrano, sarà trasmessa in differita da Rai Uno. La regia è affidata a Giovanni Cappuccilli.

LA REPUBBLICA

Riccardo Muti e il suo teatro