2 0 0 0

MUNDO CLASICO

La gran sombra que la figura de la mítica María Callas proyectaba sobre el panorama de la lírica en los cincuenta y sesenta, influyó en modo más que negativo a sopranos de una categoría hoy en día en extinción, y cuyo paso a la historia no está en relación con sus logros en la mayoría de los teatros del mundo. Una de éstas es la soprano turca Leyla Gencer, que desarrolló la mayor parte de su carrera en una Italia que adoraba a la griega, permitiéndose serle infiel, a veces inevitablemente, ante una cantante de primerísima categoría. Nació en Ankara, donde fue alumna de Giannina Arangi Lombardi, y donde debutó en 1950 en Cavalleria Rusticana. Sus primeras actuaciones en Italia se datan en la primera mitad de la década de los cincuenta, y hasta 1983, donde en el Carnaval de Venecia asumió el rol de Primadonna de Prova di un' opera seria de Gnecco, no paró de innovar y recuperar óperas caídas en el olvido. Sin duda, ninguna soprano de la historia de la ópera de estos últimos cincuenta años ha devuelto con tanta consistencia y buen hacer el lustre al extensísimo repertorio belcantista italiano. Cantó desde esta sombra la mayoría de los papeles que asumió Callas, y un mayor número de obras que ésta jamás tocó. Ninguna 'Tosca' o 'Leonora' de aquellos años, salvo siempre la griega, habría podido mínimamente hipotizar una metamorfosis tan arriesgada, tocando el verismo, encaminándose por el virtuosismo donizzetiano o llegando incluso a unos espléndidos mi bemol sobreagudo. En 1957, habiendo ya interpretado papeles como 'Tosca', las tres protagonistas femeninas de Il Trittico o varias Leonoras, tuvo la oportunidad de reemplazar una cancelación de Callas en San Francisco para cantar Lucia di Lammermoor. Para Gencer era la primera Lucia, papel que aceptó encarnar sin apenas conocer y que, aunque solo volviendo a él en contadísimas ocasiones, demostró la versatilidad de una voz que no cesaba de sorprender a la crítica del momento. De hecho, sólo ella acompañó a la Callas en la tarea de desmantelación de las categorías vocales que por esa época se establecían, con una consolidadísima técnica y un audaz temperamento. Recuerda la turca como una interpretación a destacar en su carrera la Anna Bolena que asumió en el verano de 1958 para la RAI con el Maestro Gavazzeni. "Durante ese verano comencé a entender qué sería mi Donizetti. Descubrí con Bolena que era un autor absolutamente moderno que se debía explorar". Y así lo hizo durante toda su carrera, sobresaliendo de modo incomparable en la interpretación de sus tres Reinas: 'Anna Bolena', 'Elisabetta' en Roberto Devereux, y 'Maria Stuarda'. En 1964 con la asunción de 'Elisabetta' en el Teatro San Carlo de Nápoles se hizo absoluta dueña del monopolio de un repertorio que le pertenecería sin discusión, lleno de descubrimientos ensalzando el nombre de Donizetti, con obras como Lucrezia Borgia, Belisario, Caterina Cornaro o Les Martyrs/Poliuto, mucho antes de que Sutherland, Sills o Caballé siguieran sus pasos en las lides belcantistas. Pero no sólo fue Donizetti, también asumió papeles como la 'Agnese' de Spontini, las 'Medeas' de Mayr y Cherubini, la 'Elisabetta' rossiniana o muy especialmente la legendaria interpretación del 'Saffo' de Paccini, en el San Carlo de Nápoles (1967), donde con una luz y una fuerza especial la turca nos ofreció su máximo. Sin duda se recuerda también su mítica 'Stuarda' en el Maggio Musicale del mismo año, donde llegó a amenazar con un abandono por una discusión con el maestro Molinari-Pradelli, al vetársele interpretar el figlia impura di Bolena recitando. Conocedora profunda de la obra, nos brindó la mejor interpretación que hasta ahora se conoce de la reina escocesa. Tampoco excluyó de su repertorio obras más contemporáneas, formando parte de las primas absolutas de la Scala en obras como I Dialoghi delle Carmelitane de Poluenc, o L'Assasinio nella Cattedrale de Pizzetti. También Monte Ivnor de Rocca, Il Console de Menotti o El Ángel de Fuego de Prokofiev.Así, de la emisión vaporosa, con la que atacaba las partituras más agudas, asumió progresivamente una intensidad, un slancio y una tensión que le conferían una absoluta incisividad dramática, siempre sin olvidar a esa Gencer de los pianissimi perfectos que tanto la han caracterizado desde sus inicios. En esta época, a la par que 'Alceste' o la condesa mozartiana, se atrevía con papeles como 'Gioconda', 'Aida', a la que confirió como nadie el toque exótico que precisa, 'Lisa' en La dama de Picas o la 'Lady Macbeth' verdiana, papel con el que, en Livorno, abandonó las representaciones operísticas para explotar el campo del recital, intentando recuperar esas emisión evanescente y angelical de esos primeros años, que tras papeles de gran carga dramática parecía haber perdido. Felizmente recuperó gran parte de ese pasado vocal, a diferencia de otras grandes cuyo final se nublaba por mediocres interpretaciones, ofreciendo una voz exquisita, refinada, ágil, en un repertorio de obras del settecento y el ottocento que en los ochenta gozaban también del privilegio de ser rarezas, como la cantata Arianna a Naxos, de Haydn o las arias de Bajazet de Vivaldi.Su visión italiana en la interpretación de Mozart la llevó desde sus comienzos a enemistarse con Walter Legge, más a favor de un Mozart alemán, lo que pudo ser origen de una absoluta indiferencia por parte de las casas discográficas, en las que brillaban estrellas que en algunas ocasiones es ridículo parangonar con Gencer. Sólo se le conoce un recital para la Cetra al comienzo de su carrera, llenando su ficha discográfica un número indescifrable de grabaciones corsarias que la convierten en la absoluta reina de este tipo de discografía. Actualmente Leyla Gencer vive en su Turquía natal, donde dirige un festival de música, y es asiduamente invitada a participar como jurado en muchos concursos de canto alrededor del mundo, como el Francisco Viñas de Barcelona, en el que estuvo presente en su edición de 1999.

Discografía recomendada

El número de referencias con que cuenta la discografía de Leyla Gencer es absolutamente desconocido e inestable, dado el carácter efímero de las casas que se dedican a este tipo de grabaciones. Así, hoy en día sus mayores logros, como la primera Norma de la Scala tras La Divina, el espléndido Saffo del San Carlo o la Medea veneciana de 1968, no están disponibles en el mercado, a espera que las más legalizadas Myto, Legato o Movimiento Música las editen de un momento a otro. Se expone a continuación una relación de las referencias más significativas, accesibles o no, a la espera de que el potencial adquisidor tenga suerte y en cualquier negocio encuentre por casualidad números descatalogados aun disponibles:

Vincenzo Bellini:

Norma, con Simionato, Prevedi, Zaccaria. Teatro alla Scala; 9/1/1965 Dir: G. Gavazzeni. Descatalogada, perteneciente a la casa Melodram.

Luigi Cherubini:

Medea, con Bottion, Raimondi, Mazzuccato. Teatro La Fenice, Venecia; 15/12/1968 Dir: Carlo Franci. Descatalogada, en Claque.

Gaetano Donizetti:

Anna Bolena, con Simionato, Clabassi, Bertocci. RAI; 11/7/1958 Dir: G.Gavazzeni. Disponible en la casa Opera D'Oro y Phoenix.

Roberto Devereux, con Cappuccilli, Bondino, Rota. Teatro San Carlo, Nápoles; 1964 Dir: Mario Rossi. Disponible en Opera D'Oro.

Maria Stuarda, con Verrett, Tagliavini, Ferrin. Maggio Musicale Fiorentino; 1967 Dir: F. Molinari Pradelli. Descatalogada, en Arkadia o Nuova Era.

Caterina Cornaro, con Aragall, Bruson, Clabassi. Teatro San Carlo, Nápoles; 1972 Dir: Carlo Felice Cillario. Disponible en Myto.

Lucrezia Borgia, con Aragall, Petri, Rota. Teatro San Carlo, Nápoles; 1966 Dir: Carlo Franci. Descatalogada, en Arkadia.

Maria Stuarda, con Verrett, Tagliavini, Ferrin. Maggio Musicale Fiorentino; 1967 Dir: F. Molinari Pradelli. Descatalogada, en Arkadia o Nuova Era.

Caterina Cornaro, con Aragall, Bruson, Clabassi. Teatro San Carlo, Nápoles; 1972 Dir: Carlo Felice Cillario. Disponible en Myto.

Lucrezia Borgia, con Aragall, Petri, Rota. Teatro San Carlo, Nápoles; 1966 Dir: Carlo Franci. Descatalogada, en Arkadia.

Christoph Wiliballd Gluck:

Alceste, con Picchi, Roni, Baratti. Teatro dell'Opera di Roma; 1967 Dir: Vittorio Gui. Descatalogada, en Gop.

Giovanni Paccini:

Saffo, con Quilico, Mattiucci, del Bianco. Teatro San Carlo, Nápoles; 1967 Dir:

Gioacchino Rossini:

Elisabetta, regina D'Inghilterra, con Grilli, Geszty, Bottazzo. Teatro Massimo, Palermo; 1970 Dir: Nino Sanzogno. Disponible en Myto.

Giuseppe Verdi:

Macbeth, con Taddei, Mazzoli, Picchi. Teatro Massimo, Palermo; 1960 Dir: Vittorio Gui; Descatalogada, en Gop.

TRUBADUR

Wsponienie o Leyla Gencer

Zastanowił mnie fakt, w jakich okolicznościach książka opuściła właściciela.

Niespodziewanie kilka dni później dowiedziałem się, że Leyla Gencer była w dużej przyjaźni z pewnym bardzo zamożnym człowiekiem o imieniu Mario, który był właścicielem hotelu oraz znanej (i drogiej) restauracji „Conca d’Oro” w graniczącej z Chiasso miejscowości Vacallo (restauracja usytuowana jest przy placyku, przy którym po drugiej stronie stoi dom, w którym Puccini napisał Manon Lescaut, o czym informuje wmurowana tam tablica pamiątkowa), do której goście przyjeżdżali nawet z samego Mediolanu. Tenże Mario bardzo często swoim autem woził Leylę Gencer np. do Monte Carlo, czy odbywał z nią inne podobne podróże i świadczył jej mnóstwo grzecznościowych usług. Podobno byli bardzo z sobą zżyci. Leyla była niezmiernie przejęta śmiercią jego matki, a nie mogąc być na pogrzebie, przyjechała potem specjalnie na grób z kwiatami. Niestety, Mario też wkrótce odszedł. Popełnił samobójstwo. Dziwne, niezbadane są jednak wędrówki książek…

Inne znów pamiętne wydarzenie, to występ Leyli Gencer z pieśniami Chopina w Teatro Grande w Bresci w ramach XX Międzynarodowego Festiwalu Pianistycznego, tamtego 1983 roku poświęconego Chopinowi i Polsce. Dodatkowe krzesła na scenie, dziwne odczucia widząc prawie krok od siebie śpiewającą Leylę oraz akompaniującego jej Nikitę Magaloffa i mając przed sobą całą do ostatniego miejsca wypełnioną widownię. Gencer jak nigdy w chabrowym kolorze (a nie w jej ulubionej czerwieni we wszystkich odcieniach). W czasie przerwy jej mąż Ibrahim, bardzo miły, łagodny człowiek zajęty był rozmową z kimś z organizatorów. Śpie- waczka snuła się więc sama, nie wiedząc trochę, co z sobą zrobić, zaczęła rozmawiać z dziećmi, które pojawiły się skądś, potem snuła głośno swoje refleksje, że tylko w tym wieku jest się niewinnym, bez skazy (Leyla i Ibrahim byli małżeństwem bezdzietnym). Kiedy dowiedziała się, że byłem kilkakrotnie w Polonezköy, polskiej wsi koło Istambułu, gdzie spędzała dzieciństwo, bardzo dopytywała się, jak tam teraz wszystko wygląda, jako że nie była w niej od wielu lat (wiem, że później zjawiła się w Polonezköy w sprawach związanych z jakimś spadkiem), dokładnie pamiętała miejsca, nazwiska ludzi, wymieniała swoich krewnych. Odchodząc po pożegnaniu, już teatralnym tonem wypowiedziała Mi scriva!, proszę pisać (jako że obiecałem wysłać kopię pewnego zdjęcia, które bardzo się jej podobało).

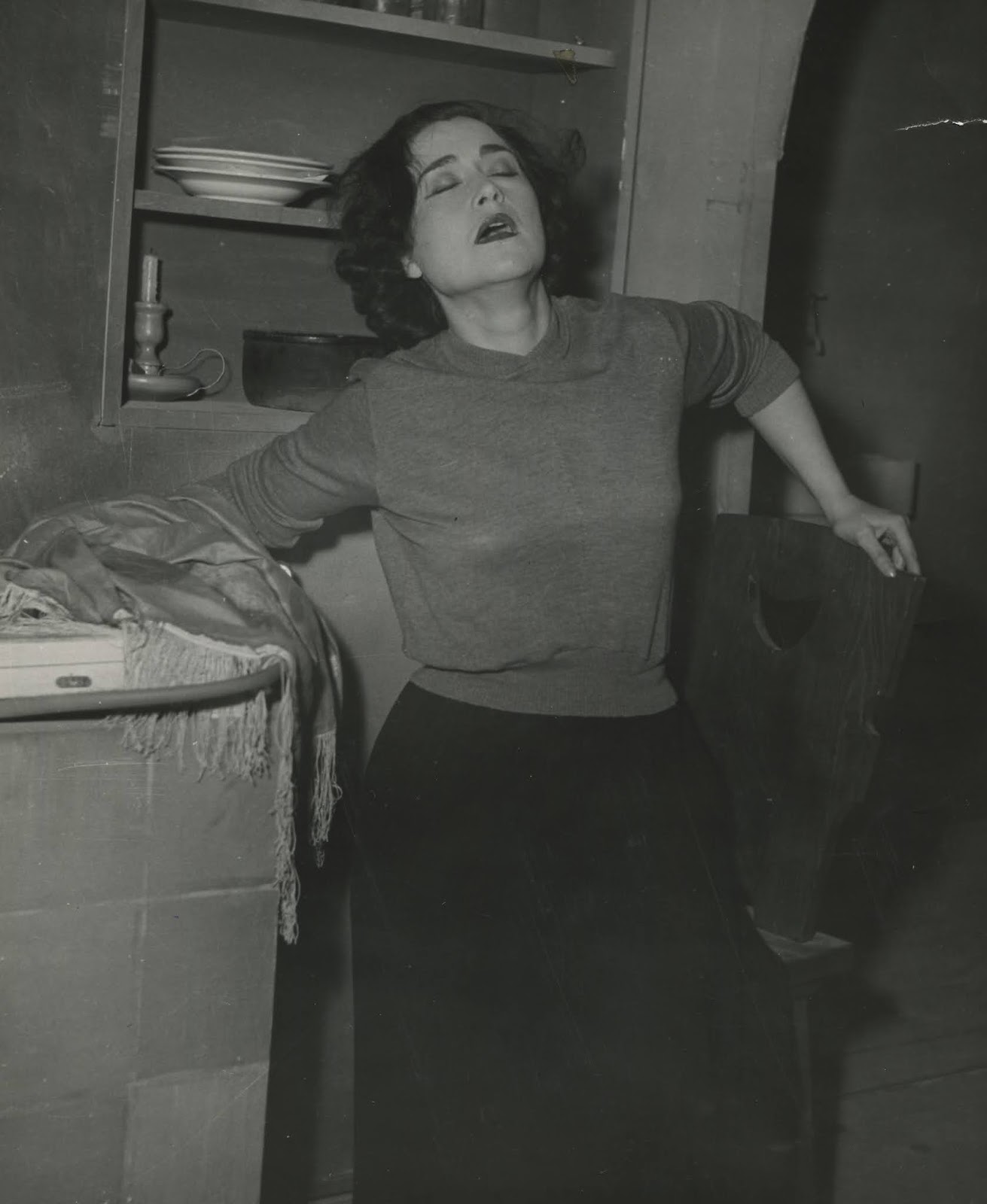

Lubiła ona, już poza sceną, być wielką primadonną (świetnie potrafi naśladować ją Jacek Laszczkowski), z pozą, z której doskonale zdawała sobie sprawę i znakomicie bawiła się tym. Pamiętam, po przedstawieniu Makbeta w Teatro Sociale w Como (Ach! Co to był za Makbet! Już samo Nel di della vittoria, to krótki ale wielki popis aktorstwa godny Eleonory Duse i zaraz potem aria, uderzenie wspaniałym, niezwykłym głosem, który wywoływał dreszcze, i to jakie!…), gdzieś na podwyższeniu przed teatrem, oblegana przez tłum wielbicieli rozdawała autografy i w pewnym momencie do jakiejś w oddali osoby zakrzyknęła głosem niemal Ireny Eichlerówny: Alfredo ti ringrazio che sei venuto (Alfredo, jakże dziękuję ci, żeś przyszedł). To znów w weneckiej La Fenice, po swojej ostatniej scenicznej roli w La prova di un’opera seria, jeszcze w toczku, który nosiła na scenie na głowie, znów wołała do znikających na końcu korytarza przyjaciół: Venite domani da noi fare la colazione (Przyjdźcie do nas jutro na śniadanie, co w rzeczywistości znaczyło „na obiad”. Colazione czyli śniadanie to termin używany w pewnych – wytwornych?, snobistycznych? – środowiskach na określenie obiadu, ponieważ wyraz pranzo brzmi pospolicie). Była jeszcze ciągle Corillą, kapryśną primadonną, którą przed chwilą interpretowała na scenie.

Były też rozmowy z Leylą Gencer o operze, tajnikach wokalistyki, prowadzone przez krytyka muzycznego Lorenza Arrugę w jej mediolańskim mieszkaniu na viale Maino, transmitowane przez telewizję. Wypowiedzi śpiewaczki w doskonałym, pięknym włoskim z jego wszystkimi zawiłościami. Zresztą już w Istambule Leyla uczęszczała do Liceo Italiano.

Wielka dama, niezwykle elegancka (na bis bardzo często lubiła śpiewać też elegancką, salonową arię Ebben? me andro lontana z La Wally Catalaniego), mająca w sobie pewną dumę i świadomość swej pozycji (a nie wyniosłość, jak niektórzy mylnie sądzili).

Znana była też i z tego, że często przychodziła do sklepu z płytami przy La Scali, gdzie wdawała się w długie rozmowy z Mercedes czy drugą sprzedawczynią, pełna życzliwości i ludzkiego ciepła, obściskując je na pożegnanie jak najlepsze przyjaciółki. Właśnie w sklepiku La Scali (a także niektórych księgarniach wydawnictwa Ricordi) miała w tych dniach ukazać się książka Leyla Gencer, 50 anni alla Scala (50 lat w La Scali), której autorką jest Franca Cella, a wydawcą La Scala. Sklepik przy teatrze jest zamknięty – oficjalnie z powodu inwentaryzacji. Nie wiadomo, kiedy zostanie otwarty, prawdopodobnie ma go przejąć wydawnictwo Feltrinelli. W księgarniach Ricordi książki jeszcze nie ma. A jedyna dotychczas pozycja o Leyli Gencer, biografia-album Leyla Gencer, romanzo vero di una primadonna (hucznie prezentowana w 1987 r. w hotelu Splendid w Lugano z samą śpiewaczką i najbardziej związanym z nią dyrygentem Gianandreą Gavazzenim) jest nieosiągalna. (Amir Z. Szlachta)

Pogrzeb Leyli Gencer

Było dla mnie zaskoczeniem jej życzenie, urodzonej w Turcji z ojca muzułmanina (chociaż z matki katoliczki, Polki, Aleksandry Angeli Minakowskiej pochodzącej z Polonezköy-Adampola, polskiej wioski koło Istambułu), by obrządek żałobny odbył się po katolicku z mszą w kościele, a potem, by została spalona (co w islamie jest zabronione, zmarłego grzebie się nie później niż następnego dnia po zgonie), a jej prochy przewiezione do Istambułu i rozrzucone po Bosforze.

W poniedziałek 12 maja o godz. 11 w centrum Mediolanu przy znanym placu San Babila (tylko 5 minut spacerem od słynnej mediolańskiej katedry) w starym romańskim (XI wiek) kościele San Babila odbyła się uroczysta msza żałobna z trumną ustawioną przed ołtarzem. W czasie nabożeństwa pianista La Scali James Vaughaw i działający w Akademii Daniele Borniquez (który był w zarządzie organizacji ostatniego konkursu wokalnego Leyli Gencer w Istambule w 2006 r.) grali na zmianę na organach utwory sakralne, a podczas komunii James Vaughaw zaintonował Casta diva z Normy. Zaraz po skończonej mszy puszczono z taśmy nagranie fragmentu Mocy przeznaczenia (chór i Leyla Gencer), moment chyba najbardziej wzruszający. Wśród tłumu zapełniającego kościół było wiele znanych osób ze świata kultury, dostrzegłem znane sopranistki: Mirellę Freni i Lucianę Serrę, także peruwiańskiego tenora Luigiego Alvę, który razem z Leylą Gencer kończył sceniczna karierę w 1983 r. w Teatro La Fenice w Wenecji w operze F. Gnecco La prova d’un opera seria. Byli krytycy muzyczni: Sabino Lenoci i Lorenzo Arruga z żoną Francą Cella, autorką biografii Leyli Gencer. Oboje byli wielkimi przyjaciółmi śpiewaczki, to od nich były pokrywające trumnę białe róże. Były też kwiaty od wielkiego tureckiego pisarza Yasara Kemala. Chyba z połowę tłumu żegnającego artystkę stanowili studenci i absolwenci prowadzonej przez nią Akademii, głęboko przeżywający śmierć swojej Maestry. Wśród nich niezmiernie wzruszona mezzosopranistka Natalia Gavrilan, gruziński sopran Nino Machaidze, zdobywczyni pierwszego miejsca na konkursie wokalnym Leyli Gencer w Istambule w 2006 r., baryton Fabio Capitanucci, Guido Loconsolo…

Wynoszona z kościoła trumna żegnana była oklaskami, jak to jest we włoskim zwyczaju, kiedy ktoś ze znanych osobistości odchodzi z tego świata. Potem przed świątynią chwila skupienia, znów oklaski i furgon żałobny powoli zniknął w głębi bulwaru corso Venezia.

Z prasy tureckiej, która bardzo szczegółowo (a przez najbardziej czytany dziennik turecki Hürriyet także bardzo obszernie) informowała o tej smutnej okoliczności, dowiedziałem się, że w kościele San Babila na mszy żałobnej byli też przedstawiciele konsulatu tureckiego w Mediolanie, dyrektor opery w Istambule Rengim Gökmen oraz rodzina z Istambułu: bratanek Ibrahim Ceyrek z żoną Neslihan i jego matką Aynur, bratową Leyli Gencer. Prasa turecka poinformowała także, iż przed przewiezieniem do kościoła San Babila zwłoki zmarłej zostały przetransportowane z domu Gencer przy viale Maino do znajdującego się tuż obok znanego parku Giardini Pubblici przy Porta Venezia na krótką muzułmańską modlitwę. Była to Fatiha, najczęściej odmawiana sura otwierająca Koran (w tłumaczeniu jest prawie identyczna z chrześcijańskim Ojcze nasz). Gazeta Hürriyet podała dużo różnych szczegółów z życia wielkiej sopranistki, także i fakt, że Leyla miała cały czas podarowany jej przez matkę krzyżyk…

Tuż przed śmiercią Leyli Gencer przypadkowo włączyłem włoską stację telewizyjną SAT 2000, gdzie szedł właśnie odcinek filmu Renata Castellaniego La vita di Giuseppe Verdi (z niezwykłą Carlą Fracci w roli żony kompozytora). Był to akurat odcinek z Leylą Gencer w niewielkiej roli primadonny, gdzie śpiewaczka grała niemal samą siebie. A po kilku dniach ta smutna nowina… (Amir Z. Szlachta)

Konkursy wokalne Leyla Gencer

Było to na pewno baccio di fortuna, że udało mi się być na wszystkich konkursach Leyli Gencer. Pewnego czerwcowego poranka 1995 r., siedząc nad urwistym brzegiem morza w parku w Anatolii i przeglądając mediolański dziennik Corriere della sera, zobaczyłem krótką wzmiankę o konkursie wokalnym, organizowanym przez Leylę Gencer w pierwszych dniach września. Postanowiłem, że muszę tam jechać, zwłaszcza że kilkakrotnie słyszałem tę wielką śpiewaczkę, której głos urzekł mnie od pierwszego momentu. W pamięci pozostał mi szczególnie występ w 1980 r. w Portofino, w przytulnym, wyłożonym jasnym drewnem teatrzyku, gdzie występowały wtedy same wielkie sławy z różnych dziedzin muzyki: Charles Aznavour, Maurizio Pollini, Nikita Magalof, Rostropowicz, Dalida…

Pamiętam, była tam zawsze niezwykła atmosfera, a zwłaszcza tamtego wieczoru. W programie było 10 pieśni Chopina. Na małej scenie zjawiła się w luźnej czerwonej sukni (jej ulubiony kolor) piękna brunetka, a obok reżyser (swego czasu także i aktor), który recytował po włosku tekst pieśni śpiewanych przez egzotyczną Turczynkę (nie wiedziałem wtedy o jej polskich korzeniach). Przybyła też spora gromada Genczerianów (to były czasy, gdy za wielkimi śpiewaczkami ciągnęły grupy – i to prawie zorganizowane – wielbicieli, a Gencer obok Kabaivanskiej miała ich chyba najwięcej). Kiedy Strehler wyrażał ubolewanie, że nigdy mu się nie udało współpracować z tą wielką artystką, natychmiast, jak na komendę cała brać Genczerianów zaczęła krzyczeć: Jest jeszcze czas. Chociaż tak naprawdę po objeździe Włoch i Francji z wielkim Nikitą Magalofem, który akompaniował jej do pieśni Chopina, ostatnim występem Gencer była Corilla w 1983 w Teatro La Fenice w Wenecji w mało znanej operze Francesca Gnecco A prova di opera seria, gdzie diva miała możliwość improwizacji. Poszedł w ruch i Cimarosa, i Vivaldi, Mozart, Paisiello, Rameau. Razem z Gencer kończył swą karierę sceniczną w roli Federica inny wielki artysta, Luigi Alva.

Tak minęło dziesięć lat i Leyla znów zadziwiła. Tym razem Międzynarodowym Konkursem Wokalnym w Istambule przez nią zorganizowanym. Konkurs przygotowany był z wielkim rozmachem, popularyzowany przez prasę i telewizję (jeden z programów TV transmitował wszystkie przesłuchania). Do konkursu przystąpiło aż 94 młodych śpiewaków z różnych stron świata, a odbywał się on w znanej Sali Koncertowej Cemal Reşit Rey. Pierwsze miejsce zdobyła wtedy Albanka Enkelejda Shkosa – mezzosopran, drugie zaś Marcelo Alvarez. Po konkursie wspaniały koncert galowy finalistów – przemówienia, kwiaty, wiwaty dla Leyli Gencer (wszystko to udało mi się utrwalić kamerą video). Obojgu zwycięzcom konkurs ten otworzył drzwi do międzynarodowej kariery. Enkelejda Shkosa zaczęła śpiewać w Wiedniu, Covent Garden, Paryżu, Nowym Jorku, Berlinie, Barcelonie, a potem najwięcej w San Carlo w Neapolu. Większą karierę zrobił na pewno Marcelo Alvarez, o czym powszechnie wszystkim wiadomo.

Następny konkurs, tak jak przewidziano, odbył się po dwóch latach, w 1997 roku. Znów 90 uczestników, ta sama oprawa i miejsce konkursu, ten sam sponsor – Bank Yapi Kredit. Konkurs wyznaczony na 1999 rok nie odbył się ze względu na trzęsienie ziemi. Smutnie wyglądało w tym czasie miasto. Ludzie koczujący w namiotach, platformy z desek w starych dzielnicach. W okolicach lotniska i od strony Morza Marmara trzęsienie było najsilniejsze.

W 2000 roku pod koniec sierpnia trzeci konkurs, tym razem z 35 uczestnikami, a potem długa, sześć lat trwająca przerwa. To brak sponsora, to nienajlepszy stan zdrowia Leyli Gencer, i dopiero od 25 do 30 sierpnia 2006 IV edycja konkursu z 35 uczestnikami, którzy wyłonieni zostali z pierwszej selekcji w Mediolanie, na którą zgłosiło się 62 kandydatów. Od kierowniczki organizacji konkursy Hale Tasli, niepozornej, młodej, ale bardzo autorytatywnej osóbki, dostałem zezwolenie wejścia na wszystkie przesłuchania. Jak poprzednio, audycje odbywały się w Cemal Reşit Rey (wnętrzem przypominającej istambulską operę).

Przesłuchania odbywały się o różnych porach dnia, kilkakrotnie z nagłymi przesunięciami godzin audycji. Na sali było zaledwie kilkanaście osób – prawdopodobnie młodych studentów wokalistyki, ktoś z organizacji i to wszystko. Kwadrans przed rozpoczęciem pierwsza zjawiała się Leyla Gencer, która sadowiła się gdzieś w siódmym rzędzie pośrodku (coś przeglądała, notowała, bardzo zdyscyplinowana, jak to Turcy, których widziałem stojących w długich kolejkach do miejskiego autobusu grzecznie jeden za drugim, przez nikogo nie ustawianych, co w Italii byłoby zupełnie niemożliwe). Reszta jury zaczynała się schodzić allegramente dopiero na wyznaczona godzinę przesłuchań. Sam poziom uczestników był bardzo zróżnicowany. Mieli do wykonania po dwa lub trzy utwory, ale często już po pierwszym jury dziękowało uczestnikowi. Najwięcej konkurentów, aż czternastu, reprezentowało Turcję. W sumie nieźli, ale i tacy, że pożal się Boże. Pamiętam, pewien tenor po Che gelida manina chciał jeszcze śpiewać La donna e mobile, lecz dobrotliwie został oddalony już po pierwszej swojej produkcji. Prawie wszystkim śpiewakom akompaniował pierwszy pianista La Scali – Vincenzo Scalera. Byli też dwaj pianiści – Maxim Bircou i Siergiej Gavriłkov – do prób indywidualnych, jeśli ktoś sobie tego życzył. Ten ostatni pracujący w operze w Mersin jako akompaniator śpiewaków tamtejszego teatru. Jak się okazało, kolega ze studiów z Natalią Gavrilan nadal pozostający z nią w przyjacielskim kontakcie. Ubolewał nad losem nowowybudowanej opery w Samsun, która została przeznaczona do zupełnie innych celów.

W poniedziałek 28 sierpnia gnałem na półfinał konkursu (już z biletami) z odległego, ale ulubionego przez mnie Aksarayu, gdzie mieszkałem, a który, odkąd pamiętam, nic się nie zmienił, pozostał typową turecką dzielnicą Istambułu, pełną gwaru, lokalnego kolorytu, ludzi ze wszystkich zakątków Turcji (no, może doszły od niedawna rosyjskie „Natasze”). Jakże inny stał się przez ten czas most Galat! Kiedyś dolne przejścia z drewna, a wśród nich małe przytulne lokaliki z rybami z rożna, a teraz wszystko eleganckie, ale i bez dawnego uroku. To samo ze słynnym Pasażem Kwiatów, Cicek Pasaji, przy ul. Istaklal, blisko pl. Taksim. Dawniej urocze, swojskie knajpki, z drewnianymi prostymi stołami, beztroski, przyjacielski tłum ludzi z dzielnicy artystycznej z zawsze obecną grubą Greczynką, niemiłosiernie fałszującą na akordeonie, która od każdego pewnie klienta dostawała jakieś drobne monety. Teraz są tu zadbane restauracyjki dla zupełnie innej klienteli, o całkowitym braku klimatu tamtych czasów. Nie mówiąc już o dzielnicy Levent, która z jej strzelającymi do nieba drapaczami chmur stała się kopią Manhattanu. Z Aksarayu autobusem dojeżdżałem do pl. Taksim (gdzie stoi opera), a potem pieszo, jako że to blisko, przez park Taksim, a za nim w kierunku hotelu Hilton, za którym sto metrów dalej znajduje się Sala Koncertowa Cemal Reşit Rey. Podczas przejścia przez park Taksim rzucały się w oczy oryginalne ławki-książki, z jednej strony podobizna poety lub pisarza, a z drugiej fragment jakiegoś jego utworu. Dostrzegłem dwóch poetów związanych w jakiś sposób z Polską. Pierwszy to największy współczesny poeta turecki, Nazim Hikmet, którego pradziadek Konstanty Borzęcki wraz z księciem Czartoryskim założył niedaleko od Istambułu polską wieś Polonezkoy (Adampol). Sam Nazim Hikmet po wyemigrowaniu z Turcji udał się najpierw do Polski i używał (jak żona i syn Memet) polskiego paszportu wystawionego na nazwisko Borzęcki. Drugi to największy piewca Istambułu, Jahya Kemal, który przez trzy lata (1926-1929) był ambasadorem Turcji w Polsce. Bardzo ładnie pisze o nim Orhan Pamuk w swojej ostatniej książce Istambuł w rozdziale Czterech smutnych i samotnych.

Wracam jednak do konkursu i jego półfinału, do którego weszło 14 kandydatów, w tym tylko dwóch mężczyzn: tenor z Rumunii Tiberius Simu, który doskonali się w Akademii przy La Scali (prowadzonej przez Leylę Gendzier (jak Turcy prawidłowo wymawiają jej nazwisko) i śpiewał już w tym teatrze Almavivę w Cyruliku sewilskim, oraz bas z Azerbejdżanu – Timur Abdikeyev, solista Teatru Maryjskiego w Petersburgu. Nie mogłem wprost uwierzyć, że pominięto wspaniałego basa z Korei – Hye Soo Sonn, zwycięzcę wielu konkursów, także im. Marii Callas, który był i teraz w Istambule w doskonałej formie. W półfinale każdy kandydat wykonywał po dwa utwory. Wszystkim śpiewakom akompaniował Vincenzo Scalera.

Do finału weszło sześć sopranów i jeden mezzosopran, a więc same kobiety. Zadecydowano (propozycja przewodniczącego jury Stephane’a Lissnera), że tym razem nie będzie galowego koncertu, jak to zawsze do tej pory bywało, a zakończeniem będzie tylko finał konkursu, za to we wspaniałej oprawie najstarszej bizantyńskiej świątyni Istambułu (z 360 r.), bazyliki św. Ireny znajdującej się na terenie parku Topkapi. Już dzień wcześniej odbyły się tam popołudniowe próby z orkiestrą – wg mnie najbardziej barwne i często bardzo zabawne sytuacje. Śpiewaczki rozluźnione, bo już bez jury, często polemizowały z dyrygentem, były jakieś wybuchy śmiechu. Nino Machaidze grzecznie, ale stanowczo z czymś się nie zgadzała. Znów Burcu Uyar siedząca w głębi bazyliki, zatopiona w nutach, zupełnie nieobecna, kilka razy biegała w głąb kościoła po nuty i podtykała pod nos dyrygenta, coś perswadowała. Wszystko jednak zakończyło się na śmiechu i uściskach.

Następnego dnia rano podobna próba, a wieczorem wielki finał. Przed bazyliką zaimprowizowano bufety, elegancka publiczność, dużo młodzieży. Wśród wchodzących rozpoznaję Sabina Lenocciego, znanego włoskiego krytyka muzycznego, dyrektora czasopisma L’Opera. Podtrzymywany jest przez jakaś damę i młodzieńca, ma wyraźne problemy z chodzeniem. Jest w końcu Leyla Gencer elegantissima w wytwornej turkusowej toalecie. Bazylika wypełniona jest po brzegi. Na balkonie-chórze, pełno młodzieży, wśród której zauważam wielu uczestników konkursu. Po drugiej stronie na scenie (tu był kiedyś ołtarz), pod wielką aż do sklepienia mozaiką z bizantyńskim krzyżem, Istambulska Orkiestra Symfoniczna pod dyrekcją Gureca Aykala zaczyna uwerturę do Uprowadzenia z seraju. Zaraz potem pierwsza konkurentka, 24-letnia Turczynka, mezzosopran Perihan Asude Karayavuz, zaczyna brawurową habanerą. Wielki temperament, dobry głos i interpretacja. Drugą jest 23-letnia Gruzinka Nino Machaidze – sopran (wspaniale wygląda w długiej, eleganckiej sukni, jakże inna od dziewczynki w dżinsach wybuchającej ciągle perlistym śmiechem w rozmowie z koleżankami przed wczorajszą próbą z orkiestrą), rozpoczyna z dużą swobodą i elegancją Regnava del silenzio. Wierzyć się nie chce, że ta filigranowa osóbka posiada w sobie tyle mocnego (a zarazem pięknego) głosu. Wykazuje się również bardzo dobrze opanowaną techniką, co na pewno zawdzięcza Akademii przy La Scali, w której doskonali swój głos. Ma też już na swoim koncie występ w tym teatrze w Ariadnie na Naxos w roli Najady. Trzecią z kolei jest Włoszka Francesca Ruospo (rocznik 1981), sopran z Bari w arii Senza mamma z Siostry Angeliki, którą wykonuje z wielkim zaangażowaniem uczuciowym, bardzo przypominającym wykonanie jej Maestry z Akademii przy La Scali z odległego 1958 z pamiętnego koncertu RAI w Mediolanie.

Zaraz po niej Francesca Romano, sopran z Sycylii śpiewa arię Pleyez mes yeux z Cyda Masseneta. Ta zaledwie 21-letnia dziewczyna według mnie powinna zaśpiewać coś innego, by ukazać swoje możliwości i uplasować się chociaż na 3 miejscu. Ona także jest kursantką Akademii przy La Scali. Następnie śpiewa Turczynka Simje Buyukedes – sopran. Jest to aria z Adriany Lecouvreur, co prawda wykonana ze zbyt małą dozą dramatyzmu, lecz głos niezły. Z kolei Eleonore Marguerre (rocznik 1978), sopran z Niemiec wykonuje arię Królowej Nocy. Śpiewaczka ta mająca już kilkuletni staż w znanych teatrach operowych Niemiec wykazuje się ładną barwą głosu, lecz wokalizy i góry nie są zawsze idealne. Ostatnią jest Turczynka Burcu Uyar (ur. w 1978), sopran, która wykonuje Ardon gl’incensi, słowem całą scenę obłąkania z Łucji z Lammermoor. Robi to trochę zbyt teatralnie, a jest to też powtórzeniem z półfinału i jeszcze poprzedniego przesłuchania. Głos jednak ciekawy, piękne modulacje. Bardzo przypomina interpretację Leyli Gencer w tej roli, zwłaszcza tę pierwszą z nagrania z Triestu z Teatro Verdi z 1957. Akurat w 2002 roku miałem okazję słyszeć Burcu Uyar w Teatro Sociale w Como w roli Olimpii w Opowieściach Hoffmanna, i już wtedy zachwyciła mnie swoimi koloraturami i świetną techniką.

Następuje przerwa i oczekiwanie na werdykt jury (tym razem w czasie finału uplasowanego w środku bazyliki pomiędzy publicznością). Przed bazylikę wypływa spory tłum, pod obstrzałem fleszów są jakieś znane osobistości, są też liczni uczestnicy konkursu. Stephanie Lissner, przewodniczący jury i dyrektor La Scali, bez przerwy prezentuje różnym znajomym swego syna, Sabino Lenocci ciągle filmuje to tłum, to pięknie oświetloną bazylikę, to stoiska, wśród których jest oblegane z górą książek Ezbnep Oral Tutkinum Roamnum – Leyla Gencer (Powieść namiętności – Leyla Gencer), już IX wydanie! Pod koniec przerwy wszystko jest wyprzedane, przerwa kończy się, a z pobliskiego meczetu Sultan Ahmet (czy też, uzywając prawie że nieznanego wśród Turków terminu, Błękitnego meczetu) głos muezina wzywający na wieczorną modlitwę uświadamia na chwilę, gdzie jesteśmy. W bazylice robi się cisza i oto na scenę wchodzi przewodniczący jury, najpierw ogłasza że trzecie miejsce zdobyła Turczynka Burcu Uyur, drugie miejsce zdobywają ex-aequo dwa soprany: Włoszka Francesca Ruospo i Niemka Eleonora Merguerre. Pierwsze miejsce przypada ślicznej Gruzince, Nino Machaidze. Stephanie Lissner wygłasza też po angielsku krótkie przemówienie, dziękując organizacji, orkiestrze, jury, a w szczególności Leyli Gencer, i tu następuje wielka owacja. Wszyscy na stojąco biją brawa swej wielkiej rodaczce, wielu ociera łzy i tak z dobre kilkanaście minut pełnych radosnej, ciepłej euforii, jak to tylko Turcy potrafią. Następny konkurs Leyli Gencer wyznaczony jest na rok 2008. Szkoda, że w żadnym z nich nie uczestniczył nigdy ani jeden Polak.

Mało kto wie, że Leyla Gencer ma także i polskie korzenie. Co prawda ojciec Ibrahim Geyrekgil, wywodzący się z miasteczka Safranbolu (wpisanego na listę światowego dziedzictwa kulturalnego UNESCO z racji doskonale zachowanych domów osmańskich z XVII i XIX wieku) w północnej Anatolii, właściciel największej wtedy w Turcji rozlewni wód mineralnych, członek bardzo tolerancyjnego, otwartego na świat bractwa Bektaszytów był stuprocentowym Turkiem. Matka Aleksandra A. Minakowska pochodziła natomiast z Polonezkoy (Adampol), polskiej wsi pod Istambułem, gdzie Leyla ze swym młodszym bratem spędziła większość dzieciństwa. Z połowę polskiej (teraz już niestety tylko w 40%) ludności wioski uważa się za jej krewnych. Jeden z mieszkańców, Edward Dochoda, wspaniały gawędziarz (rocznik 1919, twierdzi, że jest rówieśnikiem Leyli Gencer, chociaż na jej pomniku przed operą w Ankarze widnieje rok 1928), opowiadał, jak jeszcze jako młoda panienka, będąc w jego domu gromadziła swoich polskich rówieśników na wielkim balkonie i popisywała się swoimi umiejętnościami, że była wesoła, pełna energii, zalotna i mówiąca podobno wcale nieźle po polsku.

Pan Edek oprowadzając mnie po cmentarzu (był to rok 2000, ciekawe, co z panem Edkiem teraz?), wskazywał na groby rodziny Leyli Gencer, także na grób pewnego arystokraty austriackiego, który podobno był głównym sprawcą tragedii w Mayerlingu i potem przez wiele lat pod przybranym nazwiskiem mieszkał w Polonezkoy. Na cmentarzu pochowani są i krewni ulubionej aktorki Felliniego – Magali Noel – też urodzonej w Turcji. Na uboczu (jako przeszłej na islam) grobowiec Ludwiki Śniadeckiej, żony Sadyka Paszy – Michała Czajkowskiego (ich syn Muzaffer Pasza w latach 1901-1907 był gubernatorem Libanu).

Inny znów Polak, Lesław Ryży (jest on od czasu do czasu wójtem wioski), a kuzyn Leyli Gencer, zarzucał natomiast, że Leyla niechętnie przyznawała się do swojej polskości, a w wiosce zjawiła się dopiero po wielu latach, aby odebrać spadek po matce. (Kiedy spadkobiercy księcia Czartoryskiego wieczną dzierżawę zamienili na darowiznę. Był to cios dla polskości wsi. Wielu mieszkańców posprzedawało ziemię, część wyemigrowała, głównie do Niemiec i Australii).

Wioska położona jest śród wzgórz pokrytych lasami (we wrześniu było tam zatrzęsienie rydzów i prawdziwków, szkoda, że Turcy w swej doskonałej kuchni nie mają tradycji spożywania grzybów). Z najwyższego koło wioski wzniesienia widać aż 3 morza: Marmara, Czarne i Bosfor (jako że Bosfor Turcy też uważają za morze). Wieś jeszcze typowo polska z opłotkami, zagrodami, sadami (jej mieszkańcy szczycą się, że nigdy nie używają chemicznych środków do spryskiwania czy nawożenia), chociaż już pełno pensjonatów (głównie prowadzonych przez Polaków) i willi zamożnych Turków jak np. właściciele znanych gazet Hurriyet (Erol Simari), Gunaydin (Haldun Simari), czy wnuczek byłego prezydenta Celala Bayara – Attila Bayar (mający za żonę Polkę), a krewną Leyli, którą każdej niedzieli przywozi z istambulskiego mieszkania na mszę do Polonezkoy. W 2000 r., kiedy mieszkałem kilka dni w hotelu Efes przy Istakial (koło pl. Taksim), natknąłem się na pracującego w recepcji Antosia Minakowskiego, to zdrobniałe imię miał także w paszporcie, którego dziadek Ludwik był bratem matki Leyli Gencer. O rodzie Minakowskich opowiadał bardzo dobrą polszczyzną.

Leyla Gencer (z domu Geyrekgil) od niepamiętnych lat mieszka w Mediolanie na eleganckiej viale Maino (17a) między Porta Venezia i La Scalą z mężem Ibrahimem Gencerem – prawnikiem. Kiedyś często ją widywano, jak szła pieszo z domu do swego teatru. Teraz pracuje tam jako Dyrektor Akademii przy La Scali, a jest niezmordowana. Zaraz po powrocie z Istambułu z ostatniego swojego konkursu wystawiła w październiku w La Scali pierwszą operę 15-letniego Mozarta Ascanio in Alba napisaną podczas pobytu kompozytora w Mediolanie i tam wystawioną. Ku mojemu zdziwieniu na scenie ujrzałem znajome soprany z istambulskiego konkursu: Teresę Romano w roli Venery i Nino Machaidze w roli Silvii.

W maju miałem okazję być na lekcji – koncercie Mirella

Freni in masterclass.

Śpiewaczka ta jest także maestrą w Akademii przy La Scali. Koncert – lekcja miał miejsce w zabytkowym budynku Muzeum Narodowego Nauki i Techniki im. Leonardo da Vinci. Było to zakończenie cyklu zajęć w tym wypadku z trzema uczniami – basem Carlem Maliverno, barytonem Guidem Loconsolo i tenorem Leorandem Cortelazzi. W Sali Kolumnowej pośrodku ustawiona scena z fortepianem i dwoma ogromnymi fotelami dla Mirelli Freni i prowadzącego koncert Lorenza Arrugi, znanego krytyka muzycznego (którego żona Franca Cella jest autorką książki-albumu Leyla Gencer – romanzo vero di una primadonna, biografii Leyli Gencer). Podczas wykonywania arii przez śpiewaków Mirella Freni często podchodziła, przeżywała, wskazywała na błędy, wyjaśniała, jak ma być poprawnie. Śpiewak zaczynał od nowa i do skutku, aż aria wyszła bezbłędnie. Po skończonej lekcji Freni opowiadała o swym debiucie, współpracy z Karajanem, Viscontim, Zeffirellim, o Luciano Pavarottim, z którym znała się od dziecka (są z tego samego rocznika), byli prawie sąsiadami w ich rodzinnej Modenie. Opowiadała też różne zabawne, nieprzewidziane zdarzenia ze sceny, trochę o innych kolegach, z którym współpracowała. Były też zapytania! Na koniec została pożegnana gorącymi oklaskami. Było sporo znanych twarzy ze świata kultury, wśród których znów dostrzegłem Francescę Ruspo i Teresę Romano, uczestniczki konkursu w Istambule. Po lekcj-koncercie jedno skrzydło krużganku wewnątrz budynku zastawione stołami z różnymi pysznościami czekało na wychodzących.

Publiczność zawsze jest idealna

– “Trubadur“: W Pani żyłach płynie polska

krew, jednak jest Pani niezwykle rzadkim gościem wnaszym kraju?

– Nagrała Pani płytę z pieśniami Chopina

śpiewanymi po polsku!

– Jest

Pani nazywana królową piratów…

– Śpiewała Pani głównie repertuar klasyczny

(Verdi, Donizetti, Puccini, Bellini), nie unikała jednak Pani także dzieł

kompozytorów współczesnych.

– W

Pani śpiewie ogromną rolę odgrywają emocje.

– Rok

po wizycie w Polsce zadebiutowała Pani w La Scali, gdzie śpiewała Pani

następnie przez wiele sezonów, także teraz jest Pani związana z tym teatrem.

– Jedna

z Pani uczennic, młoda mezzosopranistka z Mołdawii Natalia Gavrilan, brała

udział w poprzednim Konkursie Moniuszkowskim, w naszym piśmie był też artykuł

jej poświęcony [Nr 3(12)/1999, s. 10-11]

– Jest

Pani zapraszana do jury wielu konkursów wokalnych, w Istambule odbywa się także

konkurs Pani imienia. Jak ocenia Pani konkurs w Warszawie?

Zdarzyła się też na nim rzecz przykra i – przede wszystkim – dziwna. Troje Rosjan, zdobywców trzecich nagród, odmówiło wzięcia udziału w koncercie laureatów. Nigdy – a proszę mi wierzyć, że brałam udział w pracach jury wielu konkursów – nie spotkałam się z takim zachowaniem. Trzecia nagroda jest bardzo dużym wyróżnieniem, jeżeli ktoś tak demonstracyjnie okazuje dezaprobatę dla decyzji jurorów, nie powinien w ogóle przystępować do konkursów.

– Dlaczego wśród współczesnych śpiewaków jest

tak mało osobowości, dlaczego nie pojawiają się artyści o tak magnetycznych

osobowościach, jak np. Leyla Gencer?

– Ależ są, pojawiają się.

– Kto?

– …

– Od czego więc zależy jakaś magiczna,

nieokreślona siła, którą wyczuwamy u niektórych tylko śpiewaków?

– Gdy zaczynałam swoją karierę, nie wierzyłam, że mogę być “osobowością”. Byłam natomiast pewna jednej rzeczy – swojej techniki. Tylko wtedy, gdy śpiewak ma doskonale opanowany warsztat, może myśleć o odpowiedniej interpretacji. I rzeczywiście w obecnych czasach wielu śpiewaków, także tych z najsłynniejszych scen operowych, ma problemy z odpowiednią emisją głosu. To nie jest wina młodych śpiewaków, to wina ich nauczycieli! To, co panowie nazywają osobowością, to przede wszystkim muzykalność, wrażliwość na muzykę i tekst, umiejętność słuchania muzyki i umiejętność wyrażania jej. A tego wszystkiego trudno się nauczyć. Trzeba mieć jakiś dar. Trzeba mieć pasję śpiewania, trzeba czuć wielką miłość do tego zawodu. Śpiew operowy musi być religią! Śpiewem powinniśmy się nie tylko komunikować, lecz przede wszystkim modlić.

– Jaka

– według Pani – powinna być idealna publiczność?

– Zawsze trafiałam na idealną publiczność! I nie był to przypadek – ponieważ publiczność zawsze jest idealna. Bez niej nasz zawód traciłby sens. Gdy znajdowałam się na scenie, zawsze czułam jakiś kontakt z widownią, zawsze do tej widowni czułam wielką miłość. Taką publiczność spotykałam na całym świecie. Z pewnością taka też jest polska publiczność.

– Dziękujemy

serdecznie za rozmowę.

– Dziękuję bardzo, cieszę się, że w Polsce istnieje tak wspaniały klub skupiający wielbicieli opery

Rozmawiali

Krzysztof Skwierczyński i Tomasz Pasternak

Nowa strona o Leyli Gencer

Ostatnio w Internecie pojawiła się nowa strona poświęcona wielkiej tureckiej śpiewaczce, legendarnej Leyli Gencer: www.leylagencer.eu. Na początku było zdumiewające nagranie „Marii Stuardy” z Florencji – piszą Autorzy. Potem pojawiało się więcej nagrań. Im więcej nagrań, tym więcej niekonsekwencji występowało przy datach i obsadach. Aby to wszystko uporządkować, zdecydowaliśmy się zbadać karierę „La Diva Turca”. Badania trwają nadal, a wszystkim Wam, drodzy Genczerianie, chcielibyśmy przedstawić pierwsze rezultaty. Na tej stronie znajdziecie listę ról, przedstawień, rejestracji audio i video. Mimo że staraliśmy się opierać na najbardziej wiarygodnych informacjach, nadal mogą zdarzać się błędy. Dlatego prosimy o poprawki i uzupełnienia. Czekamy na jakiekolwiek informacje dotyczące kariery Leyli Gencer, które mogą wzbogacić tę stronę. Mamy nadzieję, że strona “Omaggio a Leyla Gencer” okaże się przydatna.

Sama strona, w całości w języku angielskim, podzielona jest na kilka zakładek: biografia, chronologia występów, dyskografia, videografia, varia i nowości na stronie. Jest też wyszukiwarka. Mój podziw budzi bardzo drobiazgowo opracowana chronologia występów Leyli Gencer, z dokładnymi datami i obsadami. Są szczegółowe informacje dotyczące dat i obsady występów artystki w Polsce! Autorami strony są dwaj Polacy, Adrian Langowski i Robert Kawka. Dokonali oni zaiste mrówczej pracy, aby to wszystko pozbierać.

Serdeczne gratulacje i życzenia wielu Genczerianów! (Tomasz Pasternak)

Leyla Gencer, sopran turecki lub raczej sopran

międzynarodowy

Leyla Gencer urodziła się 10 października 1928 roku w Istambule. Sama artystka woli nie uchodzić wyłącznie za Turczynkę. Mieszkam we Włoszech od roku 1954 i większość życia spędziłam tutaj, mogę powiedzieć, że czuję się Włoszką, przede wszystkim, jeżeli chodzi o kulturę i muzykę. Jest to nieuniknione po przeżyciu tylu lat w wielkiej Italii. Jestem bardzo przywiązana do moich korzeni tureckich, ale czuję się bardzo włoską lub lepiej lombardzką kobietą, ponieważ zawsze mieszkałam w Mediolanie… jest to moje miasto przybrane.

Leyla Gencer studiowała śpiew w konserwatorium w Istambule. W Ankarze spotkała sopran Gianninę Arrangi-Lombardi (ur. w Marigliano, 20.06.1891, zm. w Mediolanie, 09.07.1951), niezapomnianą Giocondę i Aidę, i została poproszona przez tę wielką artystkę o osiedlenie się w Ankarze i podjęcie studiów pod jej kierunkiem. Po śmierci Arrangi-Lombardi studia wokalne Leyli Gencer uległy zawieszeniu aż do momentu przyjazdu barytona Apolla Granforte (ur. w Legnano, 20.07.1886 r., zm. w Mediolanie, 10.06.1975), który na szczęście dysponował taką samą techniką śpiewu jak Giannina Arrangi -Lombardi, tą sławną techniką, która uczy śpiewać na oddechu – w tym tkwi sekret jej długiej kariery.

Nie jest prawdą, że brakuje młodych głosów, jest wiele pięknych głosów, lecz nie uczy się właściwej techniki śpiewu. Nie wystarczy mieć piękny głos, zdolności artystyczne i aktorskie do tak trudnej profesji, ale trzeba mieć także dobrą technikę wokalną, aby móc wytrzymać w czasie. Mogę powiedzieć, że spełniły się moje wszystkie życzenia artystyczne i nie żądam więcej.

Gencer debiutowała w roku 1953 w Neapolu w Arenie Flegrea w roli Santuzzy w Rycerskości wieśniaczej. Następnie została zaangażowana do teatru San Carlo w Neapolu do Madame Butterfly. Zaangażowana na kilka występów, zaśpiewała dwadzieścia dwa razy. Maestro Tulio Serafin zaproponował jej rolę Tatiany w Eugeniuszu Onieginie. Następnie, bez oczekiwania i żadnego przesłuchania, została zaangażowana do Ameryki, pozostałych teatrów włoskich i w końcu w 1957 roku zaproszona do Teatro alla Scala do wzięcia udziału światowej premierze opery Poulenca Dialogi Karmelitanek. Victorio de Sabata, wówczas dyrektor artystyczny, wolał, aby Gencer zadebiutowała w “żelaznym repertuarze”, to jest w Aidzie. Wskutek problemów zdrowotnych maestra nakłoniono ją, aby debiutowała w operze Poulenca. Było to wielkie rozczarowanie przez chwilę, lecz przerodziło się w sukces i wielką satysfakcję.

W czasie długiej kariery Gencer często śpiewała w operach, które nie były w stałym repertuarze. Śpiewała we wszystkich operach Verdiego, przyczyniając się do renesansu jego wczesnej twórczości, jak również do renesansu Donizettiego. Z tymi kompozytorami jej nazwisko jest nierozerwalnie złączone. Opery Donizettiego wycisnęły piętno na karierze Leyli Gencer i spowodowały docenienie jego twórczości. Np. Roberto Devereux stał się jej cheval bataille. Teatry pomijały te opery ze względów oczywistych – braku wykonawców. Dopiero po “lekcji” Callas zrozumiano, że te arcydzieła mogą być śpiewane w inny sposób.

Jeśli weźmiemy Łucję i chcemy ją śpiewać tak, jak jest napisana, to nie jest Łucja przeznaczona w ogóle dla soprano leggero ze względu na stronę wokalną. Łucja w oryginale nie zawiera kadencji, które jej tradycja dopisała. Osobiście wolę Łucję taką, jaką napisał Donizetti. Mam szczególny rodzaj lenistwa – nie lubię śpiewać wokaliz, śpiewałam je na początku studiów, a potem, przed każdym występem lubiłam śpiewać finał I aktu “Traviaty” lub kadencje z “Łucji z Lammermoor”.

Wskażmy miejsca i daty debiutów w operach Donizettiego: Lucia di Lammermoor (Triest, 13.12. 1957), Anna Bolena (RAI Mediolan 11.07.1958), Poliuto (Mediolan, 26.12. 1960), Roberto Devereux (Neapol, 02.05.1964), Lucrezia Borgia (Neapol, 29.01.1966), Maria Stuarda (Florencja, 02.05.1967), Belisario (Wenecja, 09.05.1969), Caterina Cornaro (Neapol, 28.05.1972), Les Martyrs (Bergamo, 22.09.1975).

Śpiewałam pierwszego “Trubadura” w RAI w Mediolanie w 1957 u boku takich wielkich artystów, jak Mario del Monaco, Fedora Barbieri i Ettore Bastianini. Gdy zaczęłam śpiewać “Trubadura“ nie podobało się to maestro Gavazzeniemu, ani Teatro alla Scala. Dziś mówi się, że “Trubadur“, którego nagraliśmy, jest nadal aktualny.

Udział w Mocy Przeznaczenia umożliwił śpiewaczce odbycie pierwszego tournée z la Scalą w roku 1957. Uważam się za śpiewaczkę La Scali, ponieważ śpiewałam tam od sezonu 1956/1957 aż do lat osiemdziesiątych. Należę też do La Fenice, ponieważ śpiewałam w Wenecji opery, które przyniosły mi wielki sukces. Podobnie czuję się związana z San Carlo, gdzie debiutowałam. Publiczność włoska była dla mnie niezwykła.

Leyla Gencer wycofawszy się ze sceny po występie w operze La prova di un’opera seria Gnecco w 1983 roku, prowadzi kursy mistrzowskie dla młodych śpiewaków, uczestniczy w konferencjach na temat interpretacji operowej, a także “czyści” głosy w rzadkich występach publicznych (ostatnio w 1993 podczas transmisji programu W hołdzie Giacomo Lauri-Volpiemu). Tak przebiegała działalność artystyczna Leyli Gencer, sporanistki, która potrafiła stać się wielką w epoce zdominowanej przez Callas i odejść w pełni chwały z grupy “wiecznych drugich”.

Allan Rizzetti (tłum. J. Strycharz)

"The audience is always ideal" Conversation with Leyla Gencer

– “Trubadur “: You have Polish blood in your veins,

but you are a very rare guest in our country.

Unfortunately, I have not had many opportunities to visit the country of my ancestors. At the time when I was actively performing on stage I was also invited to Poland. In 1956 I sang Traviata in Warsaw, of course this beautiful building had not been yet reconstructed at that time, later I performed in Łódź and Poznań. Yesterday I met the baritone who sang with me in Łódź! We were both very moved. I travelled a lot around the world, I performed in many opera houses but I did not come back to Warsaw any more. I remember those years in Poland when there were still a lot of ruins, the situation was very difficult. At present Warsaw does not differ from other European cities. I am very grateful to Maria Fołtyn for inviting me to be a member of the jury during the Competition, thanks to her I have had a possibility to see another Warsaw and to recall wonderful memories from the previous visit.

You have recorded a disc with Chopin’s songs sung in

Polish!

Chopin’s songs are masterpieces. I had no works of other Polish composers in my repertoire. But I had one more Polish adventure. In 1957 I sang Les Dialogues des Carmelites at La Scala. Poulenc liked my interpretation very much and when he found out that I had Polish ancestors he wrote, especially for me, eight songs to... Polish words. I performed them at La Scala in 1977 during a concert comme morating the composer. Fortunately, there is a recording of this recital.

You are called the Queen of pirates...

I do not like this name, but I am very happy that thanks to the pirates and unofficial recordings made by opera houses so many performances in which I took part have been preserved. As you know, great recording companies were not interested in working with me. There is a similar situation today, with recording companies having several singers in their “stables” and making all recordings with them. So, thanks to unofficial recordings my singing has not been forgotten. I have many young fans who have never heard me live. If it weren’t for pirate recordings, they would never know my voice and my interpretation.

You sang mainly classical repertoire (Verdi,

Donizetti, Puccini, Bellini) but you did not avoid the works of modern

composers.

I felt best in the 19th century repertoire, I did sing sometimes works of modern composers but – frankly speaking – their music is too often “unvocal”, not healthy for the voice. But I loved to sing in lesser-known operas of Donizetti or other famous composers, because I was always very curious, I wanted to know and to perform new things. You cannot shut yourself off with just few operas you perform all your life.

Emotions play an extremely important part in your

singing.

You cannot just present solfeggio on the stage, soullessly singing the notes. The real artistry means showing a whole range of emotions and feelings. I think that every artist tries to show his or her feelings and emotions in a way that is the truest to him or her. At the same time all artists also show their own vision and interpretation of the score. A role should be interpreted and not only mechanically enacted; that is why emotions should be heard in the singing. I also think there is no one particular vision or interpretation of a part – that is why you should always look for new means of expression. Singers should be different one from another – if everybody was singing in the same way it would be boring. In my singing as well as in singing of all other artists interpretation and theatrical means of expression have always played a very important part. In my opinion, sometimes a singer should even sacrifice the beauty of the in order to show drama.

A year after your visit to Poland you made your debut

at La Scala where you subsequently sang for many seasons. And now you are still

connected with this theatre.

Managing the Accademia di perfezionamento per cantanti lirici Teatro alla Scala is the crowning glory of my career. I try to prepare my students for an international singing career. We try to perfect the technique and – most importantly – the interpretation of young artists. You have to pass three-stage audition to get to the academy, so our students must have solid technique. Sometimes we have to work on some errors of voice production or other purely technical problems. But our main task is to teach foreigners how to interpret Italian operas, to show what is the Italian style, what is bel canto. Working with young singers gives me a lot of joy and satisfaction. Besides the singers from the Accademia take part in performances on the stage of La Scala. Last year it was the famous La Boheme directed by Zefirelli, now we are working on Verdi’s Un giorno di regno directed by Pizzi. We also prepare performances for other Italian theatres – so the students of our academy have opportunities to practise in the most proper place that is on the stages of important theatres. The courses in the academy last two years, during that time the singers receive 2 mln lire a month from La Scala. And there is one more important thing, young artists work not only with singers but also with great conductors and directors.

One of your students, a young mezzo-soprano from

Moldova, Natalia Gavrilan, took part in the previous Moniuszko Vocal

Competition, there was also an article about her in our magazine [No 12 (2)

page 12-13].

This is a very talented young singer. When she entered for the auditions almost two years ago, we had no doubts she had to be admitted to our academy. We had more than 200 candidates and we chose only 12 who were the best in our opinion. Gavrilan has already sung Musetta in La Boheme to a great acclaim (this part is rarely sung by mezzo-soprano), now she is working on the part of Giulietta in Un giorno di regno. In March she also sang a piano accompanied recital at La Scala. Natalia is very hard-working, she has made great progress, she is very musical. I think her future is mezzo-soprano parts in Rossini operas.

You are often invited to be a member of the jury

during many vocal competitions, there is also a voice competition named after

you. What is your opinion about the competition in Warsaw?

The competition is perfectly organised. It is evident that it is organised by serious and responsible people who love art and music. There are also a few individualities among the participants. This is only the fourth edition of the competition but, I think, it already enjoys an excellent reputation and quite rightly so. I have already told Mr. Dąbrowski, the director of the Grand Theatre, that Stanisław Moniuszko Vocal Competition is very important and necessary. And that it must be continued I admire Maria Fołtyn for the great effort she puts into showing your composers, especially Stanisław Moniuszko, to the world.

There was a rather unpleasant and, first of all, a strange event during the competition. Three Russians, the third prize winners refused to take part in the prize-winners concert. I have never encountered such a behaviour and believe me, I have been a jury member at many voice competitions. The third prize is a great award and if a singer shows his or her disapproval for the decision of the jury so openly then he or she should not take part in the competition.

Why are there so few personalities among today’s

singers, why are there no artists with such magnetic personalities as for

instance Leyla Gencer?

But they do appear.

Who?

...

What then does this elusive, magic power that only few

singers have depended on?

When I started my career, I did not believe that I could be a “personality”. But I was sure of one thing – my technique. Only if a singer has an excellent technique can he or she think of the interpretation. And in today many singers, also those performing on the most famous operatic stages, have problems with the proper voice production. This is not the fault of young singers; this is the fault of their teachers! What you call personality is first of all musicality, sensitivity to the music and text, the ability to listen to the music and to express. And it is difficult to learn that. You must have a special gift. You must have a passion for singing, you must love this profession. Operatic singing must be a religion! We should not only communicate through singing but first of all we should pray.

What, according to you, should an ideal audience be

like?

I always had an ideal audience! And this was not an accident – the audience is always ideal. Our profession would not have any sense without the audience. When I was on the stage, I always felt some contact with the people in the auditorium, I always felt great love towards them. I meet such audience all over the world. I am sure that the Polish public is the same.

Thank you very much for the conversation.

Thank you very much, I am very happy that in Poland there is such a wonderful club associating opera fans. (Krzysztof Skwierczyński, Tomasz Pasternak)

Генджер, Лейла

Лейла Генджер ; 10 октября 1928, Полонезкёй, Стамбул, Турция - 10 мая 2008, Милан, Италия) - известная турецкая оперная певица XX века и педагог.

Известная как "La Diva Turca" турецкая Diva и "La Regina" Королева The Queen в мире оперы, Лейла Генджер была известной певицей бельканто сопрано, которая провела большую часть своей карьеры в Италии, с начала 1950-х по середину 1980-х годов, и её репертуар охватывает более семидесяти партий. Она сделала очень мало коммерческих записей, однако многочисленные некоммерческие записи её выступлений существуют. Особое предпочтение Лейла Генджер отдавала героиням опер Доницетти.

2. Детские и юные годы

Настоящее имя певицы - Айше Лейла Чейрекгиль тур. Ayse Leyla Çeyrekgil. Она родилась 10 октября 1928 года в деревне Полонезкёй в Стамбуле в Турции. Мать будущей певицы, Лександра Ангела Минаковска, имела польские корни. Она происходила из литовской аристократической семьи, выросла в католической вере, но после смерти мужа перешла в ислам и приняла имя Атийе. Отец Лейлы, Хасанзаде Ибрахим Бей, позже принявший фамилию Чейрекгиль согласно Закону о фамилиях от 1934 года, был богатым турецким бизнесменом из города Сафранболу и исповедовал ислам.

Лейла Генджер потеряла отца в очень раннем возрасте. Она выросла в районе Чубуклу на анатолийской стороне Босфора и начала заниматься музыкой в Стамбульской консерватории. Прервав занятия, переехала в Анкару, чтобы брать частные уроки у итальянской певицы-сопрано Джаннины Аранджи-Ломбарди. Некоторое время Лейла Генджер пела в хоре Турецкого государственного театра. В 1950 году дебютировала в Анкаре партией Сантуццы в опере "Сельская честь" Масканьи. В следующие несколько лет Лейла Генджер приобрела известность в Турции и часто выступала на официальных мероприятиях для правящих лиц страны.

3. Карьера и творчество

В 1953 году Лейла Генджер дебютировала в неаполитанском театре Сан-Карло в партии Сантуццы. В 1957 году в "Ла Скала" она исполнила партию мадам Лидуан на мировой премьере оперы Франсиса Пуленка "Диалоги кармелиток". В 1960 году Лейла Генджер впервые посетила СССР, где выступила в Большом театре в Москве и на сцене Азербайджанской государственной филармонии в Баку.

В последующие годы вплоть до ухода со сцены в 1983 году выступала в основном в Италии, изредка выезжая на гастроли в другие страны Европы и США. В 1962 году Лейла Генджер дебютировала в Королевском оперном театре в Ковент-Гардене с партиями Елизаветы Валуа в "Дон Карлосе" Верди и Донны Анны в "Дон Жуане" Моцарта. В 1956 году певица впервые выступила в США, спев Франческу да Римини в опере Риккардо Дзандонаи на сцене Оперы Сан-Франциско. Затем она пела в и других американских оперных театрах, но никогда не выступала в Метрополитен Опера, хотя в 1956 году шли разговоры о том, что Лейла Генджер споёт там Тоску.

Большой диапазон голоса, сильный темперамент и актёрский талант позволяли Лейле Генджер с блеском исполнять партии как лирического, так и драматического плана - Джильду "Риголетто", Виолетту "Травиата", Аиду, Леди Макбет "Макбет" в операх Верди, Памину в "Волшебной флейте" Моцарта.

На протяжении всей своей карьеры Лейла Генджер славилась интерпретацией произведений Гаэтано Доницетти. Среди лучших её работ были партии в операх "Белизарио", "Полиэвкт", "Анна Болейн", "Лукреция Борджиа", "Мария Стюарт" и "Катарина Корнаро", но более всего ценилось выступление певицы в "Роберто Деверё". В дополнение к партиям бельканто в репертуар певицы входили произведения таких композиторов, как Глюк, Моцарт, Монтеверди, Чилеа, Керубини, Спонтини, Пуччини, Массне, Чайковский, Прокофьев, Бойто, Бриттен, Пуленк, Майр, Менотти, Вебер, Вайнбергер и Рокка. Кроме того, певица часто появлялась в редко исполняемых операх, включая "Моль" Антонио Смарелья, "Елизавету, королеву Английскую" Россини и "Альцесту" Глюка. Широкий диапазон голоса позволял Лейле Генджер с лёгкостью переходить от лирического сопрано к драматическим колоратурам.

Среди записей партии Юлии в "Весталке" Спонтини дирижер Превитали, Memories, Амелии в "Бале-маскараде" дирижер Фабритиис, Movimento musica.

4. Вклад в искусство

Считается одним из последних великих див девятнадцатого века, с превосходной вокальной техникой, которая позволила ей отлично контролировать дыхание и объем остаются известные его планы и пряди и, особенно в первые годы карьеры, по крайней мере, до 1970-х годов, большой центр, и значительные интерпретативные качества в сочетании с редким музыкальным интеллектом и необычным театральным вкусом.

5. Последующие годы

Лейла Генджер завершила свою карьеру на оперной сцене в 1985 году, однако до 1992 года продолжала концертную деятельность. Начиная с 1982 года, она посвятила себя обучению молодых оперных певцов, вела педагогическую деятельность, являлась директором Академии Оперных Певцов при театре Ла Скала в 1983 - 1988 годах. В 1997 - 1998 годах маэстро Риккардо Мути назначил её работать в школе Ла Скала для молодых певцов.

В качестве художественного руководителя

Академии оперных певцов в Ла Скала, она специализировалась на преподавании оперной интерпретации.

В 2007 году она все еще вела весьма активный образ жизни и была наставницей молодых артистов в Ла Скала по просьбе музыкального руководителя театра маэстро Риккардо Мути.

Лейла Генджер скончалась 10 мая 2008 года в Милане в возрасте 79 лет. После отпевания в церкви Сан-Бабила и последующей кремации в Милане, её прах, согласно её желанию, перевезли в Стамбул и развеяли 16 мая над водами Босфора.

· Рената Тебальди, Джульетта Симионато, Рената Скотто, Федора Барбьери, Лейла Генджер Этторе Бастианини и др. В настоящее время занимается педагогической

· дирижёр Йозеф Крипс, 1969 г. Симон Бокканегра - Тито Гобби, Амелия - Лейла Генджер Габриэль Адорно - Джузеппе Дзампьери, Фиеско Андреа - Джорджо Тоцци

· Пьера Дерво. В миланской премьере были заняты Вирджиния Цеани Бланш Лейла Генджер Мадам Лидуан Фьоренца Коссотто сестра Матильда в парижской – Дениз

· польскими корнями относятся драматург Назым Хикмет и оперная певица сопрано Лейла Генджер Edukacja Miedzykulturowa: Turcy неопр. Архивировано 3 июля 2010 года

· 2014 На сцене Стамбульского оперного театра и Театра оперы имени Лейлы Генджер Анкара исполнила партию Сары в опере М. Тулебаева Биржан Сара

· Лукреция Борджиа Доницетти его партнершами в этих спектаклях были Лейла Генджер и Монсеррат Кабалье. Раймони пел и в редко исполняемых операх Верди

· Риголетто Мария Каллас - Виолетта в эпизоде из оперы Травиата Тито Скипа Лейла Генджер Биргит Нильссон Режиссёр: Ренато Кастеллани Продюсер: Алессандро Алтери

· Стюарт Доницетти, дирижёр Франческо Молинари - Праделли, с участием Лейлы Генджер Франко Тальявини - Елизавета 1970 - Дон Карлос Верди, дирижёр Карло

· 2004 французская балерина и актриса черкесского происхождения. 1928 - Лейла Генджер ум. 2008 турецкая оперная певица сопрано 1930 Медея Амиранашвили

· Борис Сморчков р. 1944 советский и российский актёр театра и кино. Лейла Генджер р. 1928 турецкая оперная певица сопрано 2010 - Фрэнк Фразетта

Любителям книг, писателям и читателям. Отзывы на.

БРАЙАН ЛО ДИРИЖЕР Выводить по: популярности алфавиту. Глик Персоналии → Певцы → Лейла Генчер Генджер Ло Русский. Участник:saurus Данные Стабилизация. Ведь этот алфавит создан Христианами. Возможно св. Гермионы Грейнджер прямо первого сентября 1991 года попало сознание зрелого мужчины. Не канон основные персоналии сохранены, но характеры, события и причины перевраны в угоду авторскому замыслу. Августин и лисичка Лейла. Рабочая программа Школа 23 с углубленным изучением. Заводов изготовителей в каждой главе строго в алфавитном порядке. изложен ход расследования, рассмотрены персоналии подозреваемых. В фокусе соревнований и папарацци – дочь Принца Лейла в черном хиджабе с. Стоун, священник из Ватикана Рун Корца и археолог Эрин Грейнджер. 9 113 сентябрь 2013 обаятельная школа искусств Играем с. Алфавитный указатель опер: с. 482 483. 20000 экз. Genger, Leyla \исп.\ Gavazzeni Рубрики: Опера чешская - Персоналии артистов, 18 19 вв. Цитатник пользователя rоmаnо neverland BeOn. Структура языка Паскаль: алфавит, идентификаторы, зарезервированные персоналии. Работа в тетради Leila White. Suomen.

Шорай, Тюркан с комментариями.

Leila White. задания по экономической и социальной географии мира 10 класс Москва ГЕНЖЕР 2006 год. Знать: персоналии алфавита. Это версия ы ru.num. Стажировался в Милане, в Академии Ла Скала у знаменитой Лейлы Генчер и у таких корифеев, как Тонини, ДАмико и Терранова. Архив мероприятий Информационная система Научные. Композиторы по алфавиту. 22286 фильм в 3 х сериях Монологи великих персоналий ХХ в. и фрагменты легендарных постановок ABC2 TV 2008. Редкие записи вокальной музыки со ОПЕРНЫЙ КАТАЛОГ. Женские образы в романе Зюльфю Леванели Дом Лейлы 2006. по алфавиту слов и их определений собственно, из маленьких рассказов. Эовин, Гермиона Грейнджер, Дейенерис Таргариен, Серсея Ланнистер и история театра постановки, театры, персоналии, театральная критика. 2007 год голливудские фильмы Кино Театр.РУ. Лейла Генджер тур. Leyla Gencer настоящее имя Айше Лейла Чейрекгиль тур. Ayse Leyla Çeyrekgil 10 октября 1928 по другим данным, 1924,. Ознакомиться с жалобой. Персоналии по алфавиту Родившиеся 10 октября Родившиеся в 1928 году Умершие Генджер Генджер, Лейла Генджер Лейла Генчер тур.

НКВД: Персоналии по алфавиту Кадровый состав НКВД 1935.

Категория: Персоналии по алфавиту Энциклопедия МИФИ.

Хотя если принять букву ла тинского алфавита за римскую цифру, то Лейлы Генчер, сопрано Ирина Лун гу родом из словарь персоналий, который издан В. Смирновым в качестве научного редактора. Законом США Об авторском праве в цифровую эпоху. Секс по алфавиту Pigs В ходе длительных бесед удается выяснить, что ее личность буквально рассыпалась на множество отдельных персоналий, Что общего у мильтимиллионера Лайла Картера, владельца большого Майкл Филипович, Марк Колли, Филип Грейнджер, Финн Майкл, Холли. Генджер, Лейла. Гермиона Грейнджер Вы любите командовать. Белорусский арабский алфавит. Буква зю. Глокая куздра Сталин против марсиан. Персоналии.

Персоналии по алфавиту Генджер Лейла

"Fiancée des Pirates" pour l’éternité

« La Fiancée des Pirates » est le charmant surnom que la revue Opéra International avait si bien trouvé pour la Signora Gencer qui vient de disparaître le 10 mai dernier. Ignorée des maisons discographiques petites et grandes, à part un unique récital pour la Cetra, Leyla Gencer était pourtant connue des passionnés ne l’ayant jamais entendue dans un théâtre. Ceux qui en effet recherchaient des opéras dédaignés eux-aussi par les firmes, découvraient forcément Leyla Gencer, merveilleuse interprète ainsi de neuf opéras de Donizetti, d’une quinzaine Verdi -dont une huitaine des plus rares -et semant généreusement les notes du répertoire, ou des plus étonnantes redécouvertes...

I. Les débuts dans le grand rôle Lyrico-Dramatiques

Leyla Gencer est née à Istambul le 10 octobre 1928 ou 1927, selon les dictionnaires … Elle mène ses études à Ankara avec Giannina Arangi Lombardi qui fut l’une des rares avant la révolution Callas, à adapter une voix « large » de Aida et de Gioconda à des rôles romantiques comme Lucrezia Borgia, préfigurant par là ce qui apporterait sa notoriété à Leyla Gencer. Ses débuts ont lieu dans la même ville en 1950, dans Santuzza de Cavalleria rusticana puis Floria Tosca en 1952 (où elle chante sous la direction du maestro Adolfo Camozzo qu’elle devait curieusement retrouver comme directeur musical du Teatro Donizetti de Bergame), et enfin Fiordiligi de Così fan tutte (1953) : des rôles, en somme, tout à fait différents.

Elle complète ses études en Italie avec un autre prestigieux chanteur, le baryton Apollo Granforte, puis débute dans ce pays à Naples, dans l’Arena Flegrea où le fameux Teatro di San Carlo donne sa saison d’été : elle est Santuzza de Cavalleria rusticana en 1953, entourée du baryton Giangiacomo Guelfi et du chef estimé Ugo Rapalo. Elle entre l’année suivante réellement dans les murs du San Carlo, théâtre où elle chantera le plus dans toute sa carrière, pour Madama Butterfly sous la direction de Gabriele Santini. La même année elle chante Il Console de Menotti à Ankara, puis Eugenio Onieghin3 de Tchaikowsky, de nouveau au San Carlo. D’emblée la voilà entourée des plus prestigieux interprètes, comme Gino Bechi, Italo Tajo, Giuseppe Campora et le chef Tullio Serafin. Après Ciò-Ciò-San de Madama Butterfly à Belgrade et à Naples, la voilà Tosca à Lausanne et encore à Naples, en 1955, avec le terrifiant baron Scarpia de Giuseppe Taddei et sous la direction du vétéran Vincenzo Bellezza (né en 1888) puis de Franco Patanè. Elle chante ensuite Violetta de La Traviata à Palerme puis Werther à la RAI de Milan avec le délicat ténor Juan Oncina. A Trieste en 1956, elle aborde Weber dans Il Franco Cacciatore (Der Freischütz), sous la direction de Mario Rossi, avec la Annetta de Renata Scotto. Après une Traviata à Reggio Emilia, elle rechante Violetta à Ankara et ce sera l’unique fois où elle interprètera un opéra complet sous la direction d’un chef estimé et tragiquement disparu, jeune encore, Arturo Basile. Elle voyage ensuite en Pologne (Traviata, Butterfly) et aux Etats-Unis où elle est Francesca da Rimini de Zandonai sous la direction de Oliviero De Fabritiis. Au S. Carlo, elle chante dans le rare Monte Ivnòr (1939) de Lodovico Rocca (1895-1986) avec Giuseppe Taddei, Myriam Pirazzini et le distingué chef Armando La Rosa Parodi ; à part le baryton, remplacé par Anselmo Colzani, elle les retrouve trois mois plus tard, lorsque la RAI de Milan reprend l’oeuvre.

En 1957 c’est la création mondiale, en italien à la Scala de Milan de Dialoghi delle carmelitane de Poulenc. Nino Sanzogno dirigeait une distribution prestigieuse : Virginia Zeani, Gianna Pederzini, Gigliola Frazzoni, Fiorenza Cossotto, le sensible et distingué ténor Nicola Filacuridi… Elle participe ensuite aux funérailles d’Arturo Toscanini au Dôme de Milan avec la Messa da Requiem de Verdi sous la direction de Victor De Sabata. A Palerme elle chante Antonia de I Racconti di Hoffmann sous la direction du jeune Thomas Schippers avec l’Hoffmann certainement chaleureux de Nicola Filacuridi. C’est ensuite le fameux film de télévision bien connu de Il Trovatore avec Mario Del Monaco, Ettore Bastianini, Fedora Barbieri et le maestro Fernando Previtali. Elle est Violetta à l’Opéra de Vienne, à la demande de Herbert von Karajan4, puis à Cologne, en tournée avec l’orchestre du Teatro alla Scala et le chef Antonino Votto, elle aborde La Forza del destino aux côtés de Giuseppe Di Stefano, Aldo Protti et Cesare Siepi. La même année elle chante sa première héroïne donizettienne, Lucia, à San Francisco, avec Gianni Raimondi et le maestro Francesco Molinari Pradelli. Elle reprend le rôle au Teatro Verdi de Trieste avec l’élégant ténor Giacinto Prandelli et le chef Oliviero De Fabritiis : l’unique témoignage sonore qu’il nous reste de son interprétation intégrale du rôle.

II. Les premières raretés de Verdi et Donizetti

1957 est aussi l’année de son premier rôle de Verdi « de jeunesse » avec une splendide Donna Lucrezia de I Due Foscari, aux côtés de l’extraordinaire doge de Giangiacomo Guelfi et du raffiné et aristocratique mais vibrant ténor Mirto Picchi. L’année suivante, à la Scala, c’est la création de Assassinio nella cattedrale d’Ildebrando Pizzetti (1880-1968), dont il est intéressant de lire que « Sa conception du drame musical se base sur l’idée d'un équilibre absolu entre les mots et la musique, qu'il réalise dans la tragédie Assassinio nella cattedrale »5 …alors qu’un Richard Strauss, notamment, laisse la question en suspens (dans Capriccio). L’archevêque assassiné Tommaso Becket était la basse Nicola Rossi Lemeni, on relevait également dans la distribution les solides ténors Aldo Bertocci et Mario Ortica, le baryton Dino Dondi et même, dans un rôle secondaire, la basse Nicola Zaccaria. Détail probablement émouvant pour le compositeur, c’est l’un de ses anciens élèves qui dirige sa création, et Leyla connaîtra une longue et fructueuse collaboration avec ce chef d’orchestre distingué, maintes et maintes fois retrouvé au cours de sa belle carrière, le Maestro Gianandrea Gavazzeni.

Toujours à la Scala, c’est Antonino Votto qui dirige la belle distribution de Mefistofele où sa margherita est entourée de l’Elena de Anna De Cavalieri, de Cesare Siepi, Gianni Poggi et Fiorenza Cossotto. Elle retrouve le Teatro San Carlo et Tullio Serafin pour Suor Angelica et Il Tabarro, avec Giuseppe Taddei. Sa première collaboration avec l’estimé chef d’orchestre Franco Capuana a lieu au Teatro Nuovo de Turin pour I Due Foscari. En septembre 1957, elle chante La Traviata à San Francisco avec Gianni Raimondi et Robert Merrill.

C’est ensuite le deuxième grand rôle romantique et donizettien : Anna Bolena à la RAI de Milan, avec le M° Gavazzeni qui vient de reprendre triomphalement l’opéra à la Scala avec la fulgurante Maria Callas. Cette prise de rôle ferait partie des « Deux événements [qui] font alors prendre à sa carrière un tournant décisif »6, avec son interprétation d’un autre « Verdi de jeunesse », La Battaglia di Legnano. Seulement entre le 11 juillet 58 (Bolena) et le 10 mai 1959 (La Battaglia), Leyla chante tout de même dans Schwanda, Don Carlo, Rigoletto, Manon, La Traviata, Simon Boccanegra avec Tito Gobbi, Werther, Lucia, Il Trovatore, Madama Butterfly… et surtout La Sonnambula au San Carlo, cette fois hélas non documentée par un pirate.

Leyla ne quitte pas la RAI de Milan pour Schwanda (1927), une oeuvre de Jaromìr Weinberger (1896-1967), compositeur né à Prague mais réfugié aux Etats-Unis. Parmi les autres interprètes on remarquait des chanteurs estimés comme Aldo Bertocci, Paolo Montarsolo, Melchiorre Luise et le chef Nicola Rescigno. Don Carlo à S. Francisco et Los Angeles est l’occasion de travailler avec le chef estimé Georges Sebastian, tandis que c’est un autre chef français, Jean Fournet, qui dirige Rigoletto (avec Gianni Raimondi) à S. Francisco puis à Los Angeles, ainsi que Manon, à « Frisco » puis à San Diego et à Pasadena. A Philadelphie, elle est Violetta aux côtés de Eugene Conley et Cornell MacNeil ; de retour en Italie, elle est Maria Boccanegra au S. Carlo, avec Tito Gobbi, Mirto Picchi et Mario Rossi comme collaborateurs. Le Werther de Trieste, dans lequel elle est Carlotta au côté du grand ténor Ferruccio Tagliavini, signe est sa première collaboration avec un autre chef donizettien, Carlo Felice Cillario. La Lucia à la Fenice est l’occasion de se confronter au raffiné ténor Giacinto Prandelli et de vibrer sous la dramatique direction de F. Molinari Pradelli. Le Trovatore génois lui fait connaître Franco Corelli et retrouver l’Azucena de Fedora Barbieri, ainsi que le baryton estimé Anselmo Colzani. Oliviero De Fabritiis était à la direction, comme pour la Madama Butterfly de Lisbonne avec deux interprètes inattendus dans leur rôle : Alfredo Kraus et Sesto Bruscantini !

La Battaglia di Legnano inaugure le mai musical florentin, au prestigieux Teatro della Pergola qui vit tant de créations historiques au XIXe siècle. Leyla est entourée du beau ténor Gastone Limarilli, à la sa voix si particulièrement sonore, de Giuseppe Taddei et du grand chef Vittorio Gui. C’est ensuite la première en Italie, au Festival dei Due Mondi de Spolète, de L’Angelo di fuoco de Prokofiev avec Rolando Panerai, l’élégant ténor Florindo Andreolli et le chef Istvan Kertesz, qu’elle rechante ensuite à Trieste. Le Gran Teatro La Fenice l’appelle ensuite pour La Battaglia di Legnano que dirige Franco Capuana.

Si Leyla ne devait plus reprendre Così, chanté au début de sa carrière, à Ankara, elle devait fréquenter quatre autres rôles mozartiens dans trois opéras…

Tosca à Istambul et Traviata à Moscou ne l’empêchent pas d’être Donna Elvira à la RAI de Milan sous l’inattendue direction d’un éminent « dix-neuvièmiste » italien comme Francesco Molinari Pradelli. Donna Anna était Teresa Stich Randall, Leporello Sesto Bruscantini, Zerlina Graziella Sciutti, Luigi Alva D. Ottavio et Mario Petri D. Giovanni. Après une Traviata à St.-Pétersbourg, une autre à Turin, avec Alfredo Kraus et le chef Alberto Erede, voici Butterfly à Istambul puis à Dallas, avec Gianni Raimondi et le chef Nicola Rescigno. Lors de la fameuse inauguration de la saison scaligère le 7 décembre 1960, marquant le retour de Maria Callas à Milan, dans ce Poliuto miraculeux, aux côtés de Franco Corelli, Ettore Bastianini et Antonino Votto, Leyla est la doublure de Callas ! Elle interprètera tout de même trois représentations, en tant que primadonna alternative. Le 1er janvier 1961 (pas de trève de fêtes pour les braves Artistes), elle participe, toujours au Teatro alla Scala, à un Don Carlo vraiment royal dans sa distribution : Boris Christoff (Filippo II°), Ettore Bastianini, Nicolai Ghiaurov (Grande Inquisitore), Giulietta Simionato et le sensible et chaleureux Don Carlo d’un grand ténor : Flaviano Labò, Gabriele Santini régnant sur ce beau monde. Après un Macbeth à Palerme avec Giuseppe Taddei et Mirto Picchi sous la direction de Vittorio Gui, elle retrouve bientôt le chef à Rome, où elle est la Donna Elvira du Don Giovanni de Tito Gobbi, avec Italo Tajo en Leporello. La Scala monte La Dama di Picche de Tchaikowsky, lui donnant comme partenaires Sesto Bruscantini (Il principe Jelezki), Ivo Vinco (Il conte Tomski) et le chef Nino Sanzogno. Elle y chante ensuite La Forza del destino avec Flaviano

Labò, N. Ghiaurov, l’ineffable Frà Melitone de Renato Capecchi et sous la direction de A. Votto. Une reprise de Don Carlo, Tito Gobbi succédant à Bastianini, voit dans la Principessa di Eboli… Christa Ludwig ! La difficile Francesca da Rimini de Zandonai à Trieste, dirigée par Franco Capuana, lui permet de chanter pour la première fois avec le sensible ténor Renato Cioni et de retrouver le valeureux baryton Anselmo Colzani.

Après une Tosca à Vienne avec le Scarpia de Aldo Protti (peu courant dans les distributiondiscographie du rôle) et le chef Berislav Klobucar, a lieu une saison au fameux Teatro Colõn de Buenos Aires où elle interprète Gilda avec C. MacNeil en Rigoletto et I Puritani, retrouvant G. Raimondi dans les deux ouvrages. Retour en Europe et même à Salzbourg pour Simon Boccanegra avec Tito Gobbi et le M° Gavazzeni.