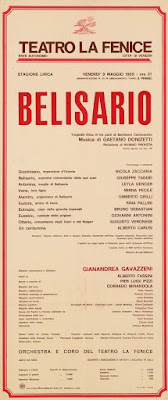

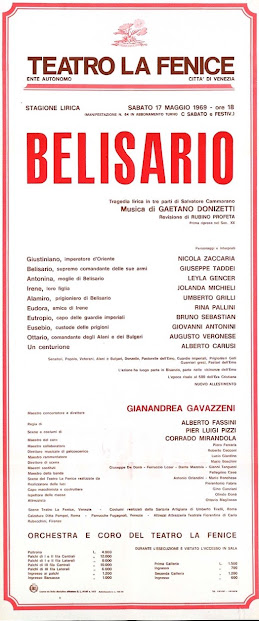

Belisario was received with great enthusiasm at its première at the Teatro La Fenice on 4 February 1836 and was given a further seventeen performances during the season. The Gazzetta privilegiata di Venezia said: "A new masterwork has been added to Italian music ... Belisario not only pleased and delighted, but also conquered, enflamed and ravished the full auditorium. However, writing to a French publisher in April, its composer said that he knew Belisario was effective in the theatre but that he himself placed it below Lucia. It went the rounds of the Italian theatres and was also staged in thirty-one cities abroad, in Europe and in the Americas. Its first London performance was on April 1837. It reached the United States first in Philadelphia, on 29 July 1843, and was heard in New York on 14 February 1844. After a production in Coblenz in 1899. Belisario disappeared until its first twentieth-century revival on 6 May 1969 when it returned to the Teatro La Fenice in Venice for the first time since 1841, with Leyla Gencer as Antonina and Giuseppe Taddei as Belisario, conducted by Gianandrea Gavazzeni. There have been subsequent performances in Bergamo in 1970 with Leyla Gencer and Renato Bruson, in London in 1972 (at Sadler's Wells Theatre, with students of the Royal Academy of Music), in Naples in 1973 with Gencer and Taddei, in Buenos Aires in 1981 with Mara Zampieri and Bruson, in London in 1981 (the Royal Academy of Music again), and in New Brunswick, New Jersey, in 1990, at Rutgers University.

Grove's Dictionary lists Cammarano's libretto as being 'after Marmontel'. However, Cammarano's primary source was not Jean- François Marmontel's 1766 novel, Bilisaire, a plea for religious tolerance, but a play, Belisarins, by Eduard von Schenk, which was first staged in Munich in 1820, and produced in Naples in 1826 in an Italian adaptation by Luigi Marchionni. Belisarius is an historical character, a general in the army of the sixth-century Byzantine Emperor Justinian. In the opera, Belisario, having defeated the Bulgarians, returns in triumph to Byzantium with prisoners all of whom he releases, except one, Alamiro, who chooses to remain with him as a kind of foster-son. Belisario's wife, Antonina, believing her husband to have been responsible for the death of their own son, denounces him to the Emperor Giustiniano as a traitor. Belisario is blinded and sentenced to exile but is later reunited with his son who is revealed to be Alamiro. After another battle in which Belisario is fatally wounded, a remorseful Antonina confesses her guilt to her dying husband.

The opera's three acts are each given titles: Il Trionfo (Triumph), L'Enlis (Exile), and La Morte (Death). Act I, Il Triunfo, is preceded by a highly engaging, if dramatically inappropriate, overture. The double arias for Irene and for Antonina are characterless and awkwardly written, and the jaunty chorus which both precedes and follows Giustiniano's dull arioso would be more suitable accompanying a quick two-step than the ceremonial appearance of an Emperor. The duet, 'Quando di sangue tinto', in which Belisario and Alamiro, unaware that they are father and son, swear to remain united forever, is the nearest approach to a love duet in this opera in which romantic love never rears its fascinating head. The duet is, however, an oddly crude piece to have come from the composer who had only some months previously written Lacis di Lammermoor. The Act I finale of Belisario is, for the most part, stiffly formal, though a larghetto ensemble, 'Non ti nascondi, o sol, brings it momentarily to life.

A very brief Act II (L'Enilio) consists of no more than an introductory chorus, an aria and cabaletta for Alamiro, and a duet for Belisario and Irene, none of which, with the possible exception of the moderato section of the duet ('Dunque andiam'), reveals Donizetti at anywhere near his best. Alamiro's vigorous cabaletta, Trema Bisanzio!", has been compared to the famous 'Di quella pira' from Verdi's Il Trovatore to which it bears a superficial resemblance, though it lacks Verdi's elemental fury. The Belisario-Irene duet, too, has been described by at least one writer on Donizetti as a prototype of Verdi's great father-daughter duets, but in this instance the comparison seems rather far-fetched.

After an orchestral introduction imbued with an almost Bellinian melancholy, the main features of Act III (La Merte) are a trio for Irene, Alamiro and Belisario with a moving larghetto ('Se il fratel stringere m'è dato al seno'), followed by the obligatory final aria and cabaletta for a remorseful Antonina who has not been heard from since Act I. The aria, 'Da quel di', is not particularly remarkable, although it can be made to sound effective by a soprano with a secure Donizetti style. Likewise, the cabaletta ('Egli è spento").

ANDANTE MMUSIC MAGAZINE

COMPLETE RECORDING

Recording

Excerpts [1969.05.14]

FROM CD BOOKLET

FROM CD BOOKLET

Belisario by Gaetano Donizetti

The phrase "unjustly neglected" is used so cavalierly and so often in regard to obscure operas that its force is nearly spent, yet in the case of Donizetti's Belisario it may still have meaning. Seldom heard today, Belisario had brilliant success at its premiere at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice on February 4, 1836, despite the fact that it contained no love scenes at all. The evening began with scattered catcalls from Donizetti detractors, but as the opera progressed the audience began to cheer, weep, applaud and shout acclaim, not only for the music but especially for the magnificent Carolina Ungher in the female lead.

The Story

Act I "Triumph." Belisario, a general in the court of the Byzantine Emperor Giustiniano (Justinian) in the sixth century A.D., returns in triumph after winning a glorious victory over the barbarians in Italy. The Senate and the people hail him, but his wife Antonina curses him instead, having heard reports that he had their own son killed. Before the Emperor and his court, Belisario magnanimously releases his prisoners, although one, Alamiro, prefers to remain at his side. Belisario welcomes him as a replacement for his slain son. Later, on forged evidence, Belisario is convicted by the Senate of treason, his enemies having conspired with his wife against him. Confronted by Antonina, he confesses to killing their son, but only because he had been commanded in a dream to do so as the only means of saving the Empire. The court expresses shock.

FROM LP BOOKLET