LA GIOCONDA

Premièr at Teatro alla Scala, Milan – 8 April 1876

Time: Seventeenth Century

Photos © CAROLYN MASON JONES, San Francisco

GENCER AT SAN FRANCISCO OPERA

LA GIOCONDA

|

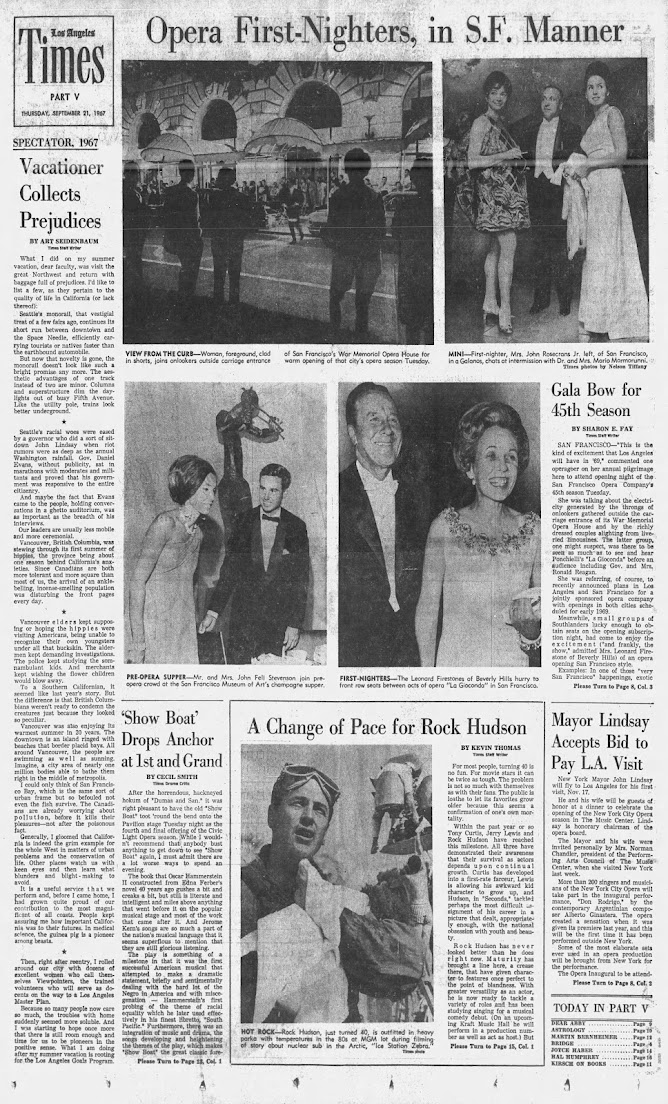

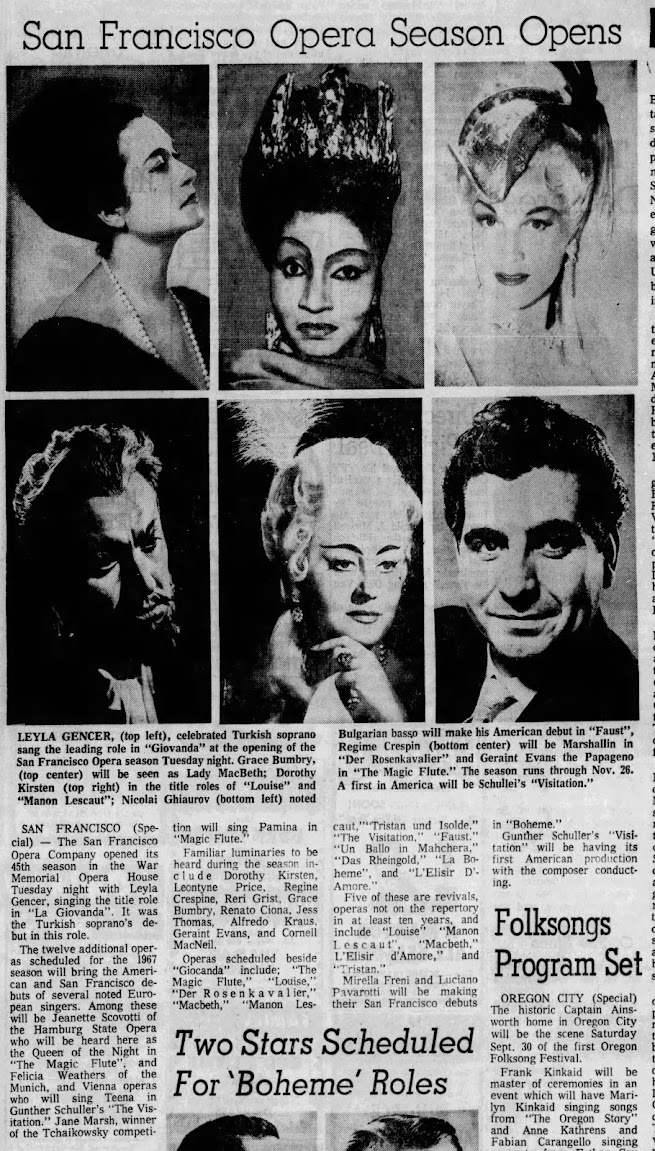

They will be working with Welsh baritone Geraint Evans (from London), American soprano Jane Marsh (From New York), American soprano Jeanette Scovotti (from Germany), British tenor Stuart Burrows" (from London), and American bass Thomas O'Leary (from Germany) and the rest of the east. Two California artists of international repute, Jess Thomas (from Bayreuth) an Irene Dalis. Opera stars from all parts of the globe are in rehearsal for the 1967 San Francisco Opera which opens its ten - week season on September 19. On hand to rehearse the opening night's "La Gioconda'' are Turkish soprano Leyla Gencer (flying from Verona), American mezzo Grace Bumbry (from Salzburg via Newport) Canadian contralto Maureen Forrester (from Pennsylvania), and Italian tenor Renato Gioni (from Milan). These artists will be having their first musical run - throughs with the dynamic young Italian conductor Giuseppe Patane (from Germany) and staging with Lotfi Mansouri (Geneva via Santa Fe) The German team of Horst Stein and Paul Hager, conductor and stage director, respectively, who teamed together for last, season's successful new "Tannhauser," are together again for the company's new tub Sack.

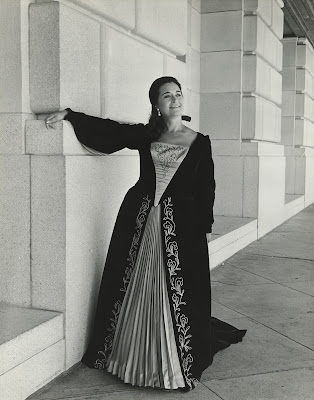

OPERA STAR Leyla Gencer breaks away from rehearsals for "La Gioconda" to stroll in Huntington Park, above, or to don a Pirovano of Milan frock for a visit to Alexis.

Photos © Seymour Snae

Diva Superstitious,

On Sept. 19 when the San Francisco Opera opens its 45th season with Miss Gencer in "La Gioconda," she'll leave her Nob Hill hotel right foot first, decorate her Opera House dressing room with photographs of her favourite Italian conductors and directors, then enter the stage right foot first.

"This will insure success," said the soprano tossing her long glossy raven locks. "The Turkish are very superstitious. See this blue pearl," she displayed another jewel. "It will protect you from the evil eye," her voice was serious, but her big brown eyes were twinkling.

Here because of another singer's illness and an emergency appeal from general director Kurt Herbert Adler who said, "Of course you can learn the role in two weeks," the La Scala star accepted the challenge, packed her good luck pieces, then added, "I must have a good prompter."

She'll also have, in spirit, her vast Italian fan club which opera hops around Europe with her. The Gencer group waved her off to San Francisco, sadly, because their budgets don't match their devotion.

Istanbul-born but Italian-trained and acclaimed, the singer expressed her delight at being back in San Francisco after nine years. Her feelings were reciprocated. At that moment, a bellboy delivered a bouquet of orchids so large he could hardly get it through the door.

Miss Gencer looked at the card, her vivid natural colour heightened, and she smiled a true "La Gioconda" smile. "Ah, it is good to be welcomed," said the soprano who made her American debut in San Francisco in 1956 in the title role of "Francesca da Rimini."

Since then, she has expanded her repertoire by 64 roles. "I added five new ones this year," explained the singer. "I don't like doing the same roles over and over. I prefer the excitement of creating something new. And this 'La Gioconda' is just for San Francisco."

After her three performances here, she'll pack her two bags and rush back to her home in a Milan palazzo. "As I increased my repertoire, I decreased my luggage. The last time I was here I had 15 bags!"

Miss Gencer exhibited a wardrobe of Italian, French, English frocks, selected a lavishly beaded short green chiffon dress as suitable for the Middle Eastern background of Alexis restaurant, then a featherweight aqua mohair coat to go over her black wool shift for rehearsals.

The soprano, who now specializes in the difficult roles of the old operas, said, "I like all those historical queens." History is one of her off-stage interests also. Archaeology was her first choice as a career, but because of her unusual voice she was urged to study with the Ankara Conservatory. She made her debut in 1951 in the Ankara State Opera, had a meteoric rise in European opera.

Although La Scala has to share her with Covent Garden, Rome, the other major houses of Europe, she said, "I am very normal in my life when possible.'

Her banker husband has headquarters in Zurich. Her friends come largely from the Italian intellectual circles. She collects antique Turkish jewellery the diamond and ruby Fatima earrings are family heirlooms - and antique English and French furniture, tours museums between operas.

"The last time I was here you had the Van Gogh collection. Now I understand there are many new things I must see." [Mildred Schroeder Hamilton]

THE SAN FRANCISCO OPERA 1922 - 1978

La Cieca was my first part as an old woman since my role in The Consul, and Lotfi knew I was insecure about how to approach it. "Now, I want you to be a big success," he said, "so do anything you want to feel comfortable in the role." But he made me think about what it must be like to be blind. I remembered how sightless people never really focus on anything in a room; their eyes stare straight ahead, blank. I played it that way, but it was more difficult to do than it sounds. By the end of the performance, my eyes would absolutely ache from fighting back the blinks.

One day I showed up at rehearsal even though I hadn't been scheduled, and Lotfi looked shocked. "Oh, darling, I'm so sorry. did you think you had a rehearsal this afternoon?" he asked.

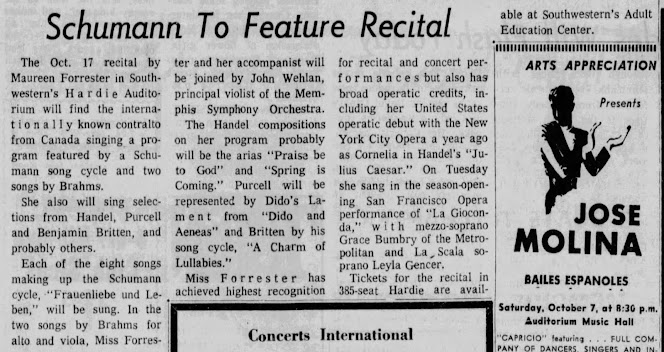

"No," I said. "But I don't know the opera, and I thought I'd come to learn it." Lotfi loved that so much that apparently, he now tells all his students that's how a pro learns an opera. But in fact, I adored the rehearsals, and I learned a lot watching- not only about La Gioconda. Leyla Gencer, a soprano with a fabled ego and temperament, was singing Gioconda and Laura was being played by Grace Bumbry, who had studied with Lotte Lehmann and was then one of the hottest of the rising young stars. At that point, Bumbry felt she had to have all the trappings of a diva, so she was always buying herself Lamborghinis and arriving in limousines a block and a half long. She must have spent all her fees on that kind of window-dressing. When Bumbry arrived in San Francisco, the rivalry between her and Gencer was palpable. They would never look at each other in a performance or take bows together. It would have been terrible if it hadn't been so comical.

One afternoon I was sitting in the audience at rehearsal beside Gencer. Bumbry was on stage singing and she was spectacular, prowling the boards like a sinewy black cat. She had an innate sexiness when she moved. "Doesn't she look just like a gorgeous sleek panther?" I said to Leyla.

"A panther?" said Leyla. "Oh, no, darling. I think of her more a spider." She paused. "A black widow."

Opera provides a field day for egos. But those star turns don't go down very well with me. I've never resented anyone else's success. As far as I'm concerned, you can't be the best; you can only be the best you can be. Everyone's voice is different and there's no point in wishing that your voice was like someone else's. Still, sometimes you overlook prima donna behaviour when you thrill to a really marvellous performance.

REGINE CRESPIN ON

GENCER

We hit it off immediately. A woman full of health, of life. And what technique! I watched her rehearse with great interest, and when she sang "Enzo adorato" at the end of the first act with its pianissimo B-flat it took my breath away. She laughed at my enthusiasm, saying, "But it's not difficult."

"For you, maybe. But how do you do it? Where do you place it?"

"There, in the buttocks," she said, giving herself a great slap on the area in question.

She took me to a restaurant, where she drank a considerable amount of vodka, to my surprise, and her beautiful face glowed with vitality.

At a dinner one night at the home of mutual friends, she pulled out a cassette and asked proudly, "Do you want to hear a high E-flat that I did?"

"It's Mission Impossible time," I said, meaning a television series I watched faithfully because it had more action than dialogue and I could understand enough to improve my halting English.

REGINE CRESPIN ON

GENCER

Mais ce n'est pas difficile !

Pour toi peut-être. Mais comment tu fais, où tu le places ?

-Là, dans les fesses bien serrées, répondait-elle, en se donnant une grande claque sur l'endroit en question !

Elle m'entraînait au restaurant où elle buvait force verres de vodka, à ma surprise, et son très beau visage éclatait de vitalité.

Je me souviens d'un dîner chez des amis communs où, sortant une cassette, elle s'écria, toute fière : "Vous voulez entendre un contremi bémol que j'ai fait ?" Mais comme c'était l'heure d'un feuilleton télévisé que je suivais avec assiduité car il y avait plus d'action que de dialogues, ce qui facilitait l'amélioration de mon anglais encore hésitant, j'annonçai à la cantonade, sans réaliser la cocasserie de la chose : "Moi, je vais voir Mission impossible !"

Heureusement, elle a ri !

Je chantai ma série de Chevalier à la rose avec un très beau succès, malgré un petit chien qui, au premier acte où l'on présente à la Maréchale des tas d'animaux, faisait régulièrement pipi sur ma robe, à la grande joie du public ! Je repartis à Marseille pour chanter... La Gioconda ! Mais grâce à Leyla cette fois j'étais prête. Je revins en 1968 pour une autre série de Troyens et de Walkyrie (que nous reprîmes en 1969 à Los Angeles). Je me souviens de mon émotion lorsque Lotte Lehmann vint me voir après une Walkyrie (elle s'était tant illustrée dans ce rôle de Sieglinde qui nous était cher à toutes deux) et ses compliments me touchèrent au cœur. La photo que j'ai de cet instant m'est précieuse.

Je ne reparlerai pas de cette année 1970, bien oubliée cependant car il m'est naturel de ne pas revenir sur le passé. Je maudis souvent ma mémoire capricieuse, mais lorsqu'il s'agit de mauvais souvenirs, je ne déteste pas cette faculté qui m'est bienfaisante.

ŞİRİN

Yazan:

Şirin Devrim

İngilizce aslından çeviren: Seçkin Selvi

Türkçe

yayın hakları: © Doğan Kitapçılık AŞ

Part 17

lstanbul'da güzel bir yaz tatili geçirdikten sonra sonbaharda San Francisco'ya uçtum. Havaalanında tiyatronun iki başoyuncusu beni karşıladı. Arabayla Stanford Üniversitesi'ne gittik. Orası bir cennet. İspanyol, daha çok da Fas tarzı bir mimari ... San taş yapılar, sütunlar, kemerler. Masmavi gök, pırıl pınl güneş, her yanda en az yirmi metre boyunda palmiyeler, renk renk, biçim biçim çiçekler. Bir de Ravenna'dan getirilen mozaiklerle döşeli Bizans tipi koca bir kilise. Kiliseye giden yolun iki yanında sıralanan palmiyeler. Bir çevreme baktım, bir de Pittsburgh'a ilk gittiğim günü düşündüm. Ne tezat ama!

TRUE TALES FROM THE MAD,

MAD, MAD WORLD OF OPERA

JOYOUS WOMAN, PART I

When it comes to my own brushes with operatic madness, Amilcare Ponchielli's La Gioconda is unusually well represented. My curse with this rarely performed work began in San Francisco in 1967, when I directed a production starring the Turkish soprano Leyla Gencer and the African American mezzo-soprano Grace Bumbry. What I was not aware of was that these singers had had a bad experience together at La Scala. In other words, they hated each other. They even refused to speak directly to each other, channellings all communication through me. In rehearsal, even if they were holding hands, Grace would turn to me and say, "Lotfi, is she going to do it this badly on the night of the performance?" Or Leyla would ask, "Lotfi, is she ever going to learn her role?" or "Is she going to cross in front of me right in the middle of my high note?"

One evening I was called into Leyla's dressing room. "Maestro Mansouri," she intoned in a syrupy voice, “please talk to La Grace. She is a ve-e-rr-y nice girl. She has got a big talent, so she doesn't need to put her hands in front of me when I am singing. And she doesn't need to step on my feet. She's ve-e-rr-y nice, you understand, but tell her it is unnecessary to do these things. You must tell La Grace these things, maestro. I cannot because, you see, in Turkey we were taught never to talk to the black servants." Needless to say, I never told Grace about this little conversation.

I had previously worked with Gencer on a production of Simon Boccanegra. And I had known Grace for ages. Back when we were students of Lotte Lehmann at the Music Academy of the West, I had even done scene work with her, singing Manrico to her Azucena in excerpts from II Trovatore. Back then she was brash and down-to-earth. But now, as a world- renowned artist, she had adopted the trappings of the archetypical diva. In fact, she had become a grande dame. She had taken to driving around in a white Mercedes, and she had acquired a trophy husband, a tenor from somewhere in Eastern Europe. I remembered this gentleman from a production of Otello in Basel, Switzerland, where his talents had enabled him to attain the position of third cover of the role of Cassio. Fortunately for him, his exceptional looks made up for his lack of singing ability. One day, during a rehearsal, she turned suddenly and said, "Look at that bastard!" Her husband was sound asleep in the auditorium. I asked Grace why she married him, and she replied, "Honey, he looks great carrying my luggage."

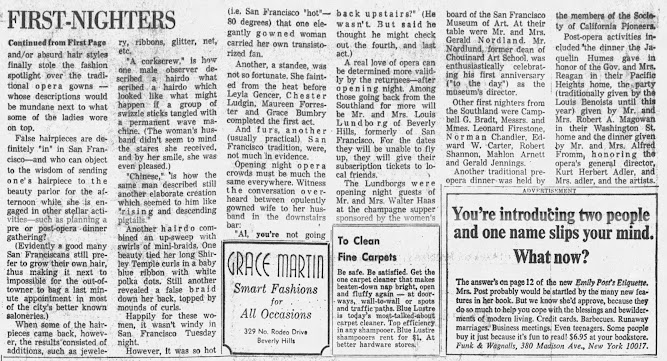

Mezzo-soprano Maureen Forrester, who played La Cieca, provided a much-needed dose of normal behaviour, and the fireworks between Leyla and Grace fascinated her. One day I saw her sitting in on one of the rehearsals even though she was not called. When I told her to go home and enjoy the rest of her day, she answered, "Are you kidding? Just watching this is a good time. I wouldn't miss it for all the world."

The curtain calls received as much attention as the performance - maybe more. Everybody from the administrative offices, including General Director Kurt Herbert Adler, would race down to see them. La Grace would sweep out - to hell with Gencer - and take a grand bow. She was a superb, statuesque lady with a wonderful physical presence - her legs got to centre stage a full minute before the rest of her. Then dumpy little Leyla would stomp out for her curtain call, only to have Grace sweep in front of her. Finally, just as she was exiting, Gencer would subtly step on Grace's train. Every night there was a variation on this sort of thing. It was the best show in town, and nobody wanted to miss a moment of it.

On opening night, following the eventful curtain call, Mr. Adler asked me to call the cast back to the stage to greet California's then- governor, Ronald Reagan, and his wife, Nancy Davis. Grace refused. It had nothing to do with politics; she simply didn't want to. She had given a fine performance, the audience had showered her with applause and flowers, and as far as she was concerned, her night was over- no matter who was in the house. I knew her well enough to coax her to the stage. The Reagans went down the line, shaking hands and having a few words with each artist. When they got to Grace, her eyes blazed through them and her smile barely concealed her displeasure at what was to her an imposition. I was standing at the end of the line, and the instant the Reagans passed her, Grace looked down the line and yelled, "Can I go now, Lotfi?" The Reagans graciously pretended not to notice as I melted in embarrassment.

Eight days after my first ever performance of Mozart’s “The Magic Flute”, I was back at the War Memorial Opera House for my first ever performance of Ponchielli’s “La Gioconda”. Of the twelve operas I would see (either once or twice) during the San Francisco Opera’s Fall 1967 season, nine of them would be “firsts” for me.

Leyla Gencer’s Gioconda

The celebrated Turkish soprano Leyla Gencer sang the role of Gioconda beautifully, demonstrating dramatic poise and vocal security. Gencer projected a passionate woman capable of self-sacrifice for persons whom Gioconda loved (her mother La Cieca and Enzo Grimaldo) or to whom she showed gratitude for another’s assistance at a life-threatening moment (Laura).

This was my first time iin a decade attending a Gencer performance, she being my first Violetta [Historical Performances: San Francisco Opera’s “La Traviata” in San Diego Stars Leyla Gencer, Robert Merrill – October 31, 1957] and my first Lucia di Lammermoor [Historical Performances: Leyla Gencer’s Stunning “Lucia” at Los Angeles’ Shrine Auditorium – November 10, 1957].

Renato Cioni’s Enzo Grimaldo

Italian lyric tenor Renato Cioni was a handsome presence, although possessing a lighter voice than I would have expected for the role of the nobleman Enzo Grimaldo. That said, Cioni ardently performed the role’s showpiece aria, Cielo e mar, another one of the greatest arias of the mid-19th century.

← Photo: Although Enzo Grimaldi (Renato Cioni, left) is the object of affection of Gioconda (Leyla Gencer, right), she will give her life to protect his happiness; edited image, based on a San Francisco Opera production photograph from the Leyla Gencer Archives

Cioni was a favourite tenor of some of the major divas of the day, including Maria Callas and Joan Sutherland. According to the Australian director Ian Campbell, Cioni inadvertently advanced the career of another Italian tenor, Luciano Pavarotti, whose San Francisco Opera debut occurred later in the 1967 fall season.

Grace Bumbry’s Laura

The role of Laura was entrusted to American mezzo-soprano Grace Bumbry. Even though married to the dangerous Alvise, Laura was Gioconda’s rival for Enzo’s love. Bumbry’s Laura was a vocal triumph, especially in the dramatic scene in which she and Gencer’s Gioconda display their rivalry for Enzo’s attention. Gioconda’s temperament changes when she discovers that Laura has the rosary that Gioconda’s mother La Cieca had given an unknown woman who saved her life.

← Photo: Grace Bumbry as Laura; edited image, based on a production photograph, courtesy of the San Francisco Opera

This was my second opportunity to be present at a Bumbry operatic performance, following her brilliant Carmen of the previous season [Historical Performances: An Exciting “Carmen” from Grace Bumbry and Jon Vickers – San Francisco Opera, November 27, 1966.]

Maureen Forrester’s La Cieca

Canadian contralto Maureen Forrester, then 37 years old (and two years younger than Gencer, who played her daughter) gave an arresting performance La Cieca. She gained audience sympathy in her affecting performance of Cieca’s great aria Voce di donna.

→ Photo: the blind La Cieca (Maureen Forrester, left) is protected by her daughter, Giocoda (Leyla Gencer, right); edited image, based on a San Francisco Opera production photograph, courtesy of the Leyla Gencer Archives

Forrester’s vocal career had been advanced by her selection by Maestro Bruno Walter as the contralto performer on his recordings of Gustav Mahler’s symphonies. Her San Francisco Opera appearance as Cieca was early in the operatic portion of her career, that blossomed in the 1970s and later years. I would see her again a decade and a half later as Madame de la Haltière in Massenet’s “Cendrillon”.

Chester Ludgin’s Barnaba

The opera contains two villains, the conniving Barnaba, an operative for the notorious Inquisition, and that evil agency’s head, Count Alvise, Laura’s murderous spouse.

← Photo: Bartione Chester Ludgin; edited image, based on an historical photograph

Ludgin, whose reputation had been established at the New York City Opera and on Broadway, had proved to be an invaluable presence in the two previous seasonsl. In 1965, he was a dramatically powerful Jack Rance (my favorite Ludgin performance of all) [See Historical Performances: “La Fanciulla del West” with Marie Collier and João Gibin – San Francisco Opera, September 26, 1965].

Ara Berberian’s Alvise and Other Cast Members

Bass Ara Berberian exuded the villainy and sonorous deep voice required of a successful Alvise.

← Photo: Alvise (Ara Berberian, right) confronts La Cieca (Maureen Forrester, front center) on a charge of sorcery to the horror of her daughter, La Gioconda (Leyla Gencer, front left); edited image, based on a San Francisco Opera production photograph, courtesy of the Leyla Gencer Archives

Berberian had made an auspicious San Francisco Opera debut the previous season as Un Frate [Historical Performances – Vickers is “Don Carlo” with Watson, Horne, Glossop and Tozzi – San Francisco Opera, October 1, 1966] and then made a strong impression as Pimen [Historical Performances: “Boris Godunov” – San Francisco Opera, October 23, 1966.] He proved to be an operatic workhorse in both the 1966 and 1967 seasons with other comprimarios bass roles in several operas.

The San Francisco Opera Ballet

The San Francisco Opera corps de ballet performed the “Gioconda’s” famous Dance of the Hours. Its solo dancers were Sandra Balestracci, David Coll, Diana Marks and John DeVere.

← Photo: A scene from the “La Gioconda” ballet; edited image, based on a San Francisco Opera production photograph, courtesy of the San Francisco Opera Archives

Thanks to Walt Disney’s animated film Fantasia and an Allen Sherman novelty song from four years earlier, it is unlikely that many in the audience were unfamiliar with the melodies of the “Dance of the Hours”.

Maestro Giuseppe Patane and the San Francisco Opera and Chorus

← Photo: Giuseppe Patané

Since having been converted by BIrgit Nilsson, Jon Vickers and Geraint Evans to seeing opera up close at the War Memorial Opera House [Historical Performances: Birgit Nilsson, Jon Vickers, Geraint Evans in “Fidelio” – San Francisco Opera, October 17, 1964], this was my first opportunity to observe the conducting of 35 year old Italian Maestro Giuseppe Patane from my Sunday matinee subscription seats (that I have continued to occupy over the past 57 San Francisco Opera seasons).