LE NOZZE DI FIGARO

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 - 1791)

Opera buffa in four acts in Italian

Liberetto: Lorenzo de Ponte, after Beaumarchais.Premièr at Burgtheater, Vienna – 1 May 1786

28†, 30 June - 07, 09, 11, 13, 16, 18, 24, 27 July - 22*† August 1963

Glyndebourne Opera House, Glyndebourne

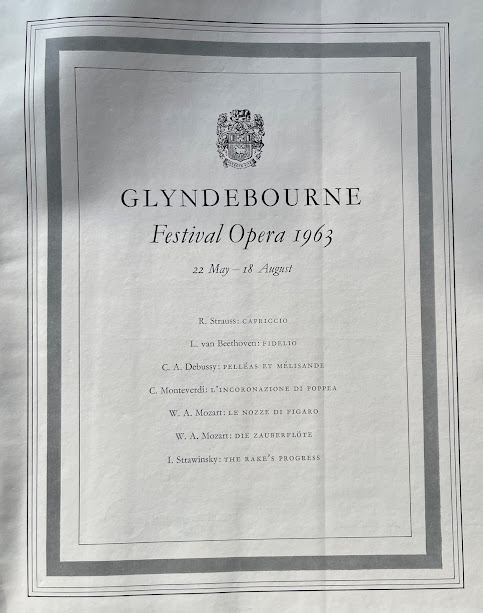

GLYNDEBOURNE OPERA FESTIVAL

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

The Glyndebourne Festival Chorus

Conductor: Silvio Varviso

Chorus master: Myer Fredman

Stage director: Carl Ebert (1955) / Peter Ebert

Scene and costumes: Oliver Messel

Choreographer: Robert Harrold

Count Almaviva MICHAEL ROUX baritone

Figaro his valet HEINZ BLAKENBURG baritone

Doctor Bartolo CARLO CAVA bass

MICHAEL LANGDON bass (13, 15, 18, 24, 27.07)

Don Basilio a music-master HUGUES CUENOD tenor

Cherubino a page EDITH MATHIS soprano

Antonio a gardener DERICK DAVIES bass

Don Curizo counsellor at law JOHN KENTISH tenor

Countess Almaviva LEYLA GENCER soprano

Susanna her personal maid LILIANE BERTON soprano

Marcellina a duenna ROSA LANGHEZZA soprano

Barbarina Antonio’s niece MARIA ZERI soprano

Bridesmaid AUDREY ATTWOOD

Harpsichord Martin Iseppe

Time: Eighteenth Century

Place: The Count’s chateau of Aguas Frescas, near Seville

† Recording dates

Photos © GUY GRAVETT, Sussex

Note: For the first time BBC TV relay a

complete opera from Glyndebourne Opera House

Cover of Programme Book © by DENNIS LENNON

Foreword by George Christie from the Festival Booklet

The inheritance of an opera house and its policy.

|

| George Christie Photo: © Guy Gravett |

Inheritance is not necessarily something to be envied. Rightly, appreciation of the success of a venture like Glyndebourne or of any project, be it an enlightened government or a small business, is directed in the first place to the person or people responsible for the establishment of that success.

Edmund Burke, in one of his letters about his proposals for peace in France during the Revolution described Alexander I of Russia on his succession to the throne after Catherine the Great as 'the inheritor of so much glory and placed in a situation of so much delicacy and difficulty for the preservation of that inheritance.... His renown will be in continuing with ease and safety what his predecessor was obliged to achieve through mighty struggles. He is sensible that his business is not to innovate, but to secure and establish.' To my mind, the future of Glyndebourne does not depend on 'preservation', on continuing 'with safety' what has in the past been achieved through 'mighty struggles', on avoiding innovation and concentrating instead upon the establishment of security for the future. Glyndebourne would become atrophied, would become a museum rather than a 'live' theatre if it were now purely a question of its preservation.

It seems to me essential that the future of Glyndebourne as a living and leading opera house of international interest must depend upon the development of a tradition created by my parents and those who to an important extent assisted them. It is not a question of sticking strictly to the methods of the past, but of developing these methods so as to merit a position of leadership in a world of changing thoughts, circumstances, fashions and so on.

What my father and mother particularly helped to do in creating and establishing Glyndebourne was to break with operatic tradition as known in this country, to contradict the static and undramatic productions, or rather performances, which were generally to be seen before the war, and with the help of Fritz Busch and Carl Ebert, to introduce a virtually new tradition opera. My parents were fortunate in the realisation of ideas which, though rarely practised in this country, found immediate acceptance. Audiences were tiring of imported performances of large-scale works sung before so-called naturalistic and shabby settings, and 'acted out' according to the whims of the singers rather than the direction of a producer. (The pre-war producer, to judge from his billing and from what I have been told of his work, was on the whole regarded as a mere technician with no properly equated artistic function.) Busch and Ebert made an immediate impact in correcting this situation in their first productions at Glyndebourne - and of course thereafter. Furthermore, so-called chamber opera was relatively seldom performed - Così fan tutte, for example, was scarcely ever staged and so the time was ripe to give the public something of which they had been comparatively starved. My parents were also fortunate in the timing of their creation in so far as economic factors in the 'thirties were concerned. Building costs (in comparison with today) were exceptionally low. Imagine, as an individual with a fair amount of capital, building an opera house today. A municipal theatre seating under 1000 designed conventionally for the less complicated demands of the spoken rather than sung word now costs in its basic form £300,000. It also costs a good deal to run once constructed. Tax was also sufficiently low in the 'thirties to allow a relatively wealthy man to meet out of his own pocket the deficit made on a two- to three-week season of opera (not the cheapest form of art).

Looking back, it seems that the timing of Glyndebourne's foundation was for these and other reasons opportune and gave possibly the last chance for a private patron to attach to his home a private opera house where first-rate artists were brought together in an almost feudal, though essentially professional, set-up, to perform before an audience brought down in a 'special train'.

The artistic policy and all its ramifications - programming, methods of musical and dramatic production, construction of additional buildings etc. – have of course been developed over the years. In the six years before the war, Mozart's operas were almost exclusively performed (Verdi's Macbeth and Donizetti's Don Pasquale being the only exceptions). Since the revival of Glyndebourne in 1946, the repertoire has of course widened enormously. The personalities involved have necessarily changed too, not perhaps in every case for the better, nor evidently in the majority of cases for the worse. Ancillary buildings have sprung up extensively. (Even though Glyndebourne has during the past 12 years become almost a village, a recent letter from France addressing my father as the Mayor of Glyndebourne implied rather more than a top-heavy impression of the size of the place.)

On the death of my mother, little in the way of general policy was instantly altered. What had until her death been realised, continued thereafter to be practised without any immediate weakening or change, even though she had to a very large degree been responsible for the formation of policy and methods during the first twenty years of Glyndebourne's existence. Similarly, now that my father has died, the basic principles on which Glyndebourne has been built up and the resulting policy and system of functioning will not consequently change all of a sudden.

There seems to be little purpose in altering something

which has been built up with a great deal of thought and care over the years,

which has in effect become to a large extent self-generating, and which has

proved and is still actively proving itself to be right in essentials and

successful in results. Developments must of course take place, but they should

surely be introduced as a logical consequence of what went before (assuming

that the previous set-up could be justified as being of real value) and as a

result of needs and circumstances at the moment of change.

With our methods of working already so deeply

ingrained, our basic policy firmly established and a profound interest in and

enthusiasm for Glyndebourne's progress amongst those working for it, the future

does not by any means look an unhappy one for me or for those dedicated to

Glyndebourne.

|

| With Peter Ebert, Stage Director and Liliane Berton, Susanna |

OPERA MAGAZINE

1963 January

UNKNOWN NEWSPAPER

1963 June

THE TIMES

1963.06.29

THE TIMES

1963.08.23

Recording Excerpt [1963.06.28]

Porgi Amor qualche ristoro Act II

E Susanne non vien! .... Dove sono i bei momenti Act III

Canzonetta sull'aria... Che soave zeffiretto Act III

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)