OPERA WARHORSES

2007.05.16

WILLIAM BURNETT

Historical Performances: Callas Fired, An Opera

Changed – San Francisco Opera’s “Aida” at San Diego’s Fox Theater, November 7,

1957

This is the eighth of ten observances of historic

performances of the San Francisco Opera that I attended during the company’s

annual tours of Southern California

When purchasing a ticket for an opera, the opera

company’s often includes the statement that “casts and operas are subject to

change”. Over time, opera goers inevitably will experience cast changes, such

as I did earlier this year at Houston’s “Faust” (see my review elsewhere on

this website). But how often does an opera company change the opera itself,

especially on short notice?

I have known three occasions, all involving the San

Francisco Opera. As the most extreme example of an opera impresario’s agony,

Kurt Herbert Adler found himself with an indisposed Elsa (Hildegard

Hillebrecht) for a scheduled performance in 1965 of Wagner’s “Lohengrin” and

found no one in the world able to produce an Elsa in time for the performance.

His solution? Noting that a performance of Rossini’s

“Barber of Seville” was the next opera on the subscription series of which the

“Lohengrin” was part and that all members of the “Barber” cast, who had

performed the previous night, were healthy and accounted for, he reversed the

dates of the two performances, allowing time for Frau Hillebrecht to recover.

As a result, the “Barber” cast had to perform on

consecutive nights and “Lohengrin” then had to be performed twice the next week

with only a day’s rest between, but that seemed a better alternative than

cancelling the first “Lohengrin” altogether.

Presumably, most of the subscribers themselves were

indifferent to the order that they would see those two operas. However, the

subscribers are not the only persons that attend a given performance. You might

imagine the anger that the opera house doormen and ushers experienced (and I

had the testimonial of one such doorman) when those patrons who were NOT

indifferent discovered that the Wagner music drama for which they purchased a

ticket was now a Rossini opera buffa and vice versa.

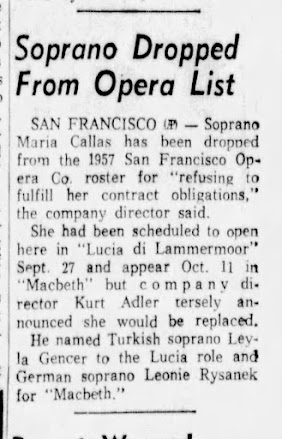

Maria Callas had been scheduled to make her debut at

San Francisco Opera in September 1957, performing four times in San Francisco,

and, on the San Francisco Opera’s post-season tour of Southern California, to

perform three times at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles and once at the Fox

Theatre in San Diego. When she failed to show up for rehearsals in September

for “Lucia di Lammermoor”, Adler fired her and, in cooperation with the Chicago

Lyric Opera and New York Metropolitan Opera, invoked a lockout of Callas in the

major United States opera houses.

No opera company general manager wants ever to be

forced to change an opera, and there will be various strategies to safeguard

the opera company against the illness or indisposition (not always the same

thing) of a scheduled performer. One strategy is to have a cover somewhere

nearby, which becomes one of the great advantages of having an

“artists-in-residence” program, such as one sees at the Met, San Francisco,

Houston and elsewhere.

Sometimes the cover is a person who knows the critical

role but is performing in one of the opera’s supporting parts. In 2000, Paolo

Gavanelli became ill for a San Francisco performance of the title role of

Verdi’s “Simon Boccanegra” and Nicholas Putilin, who performs Simon at the

Mariinsky Theatre/Kirov Opera, was cast as Paolo, who was in turn covered by

one of the company’s younger singers. With Putilin as Boccanegra and a new

Paolo, the performance proceeded with minimum despair.

One suspects that these days every general manager has

some sort of plan for replacing every important cast member of an opera they

are producing. And, I suspect, that the more problematical an important opera

star is (such as an artist who is known to cancel a lot for illness or other

reasons), the more effort goes into having carefully developed contingency

plans. If one is really suspicious of an artist, I would imagine, the opera

company would have taken multiple steps to safeguard against the consequences

of a cancellation.

Earlier this month, in preparing a tribute to the

Young Rysanek at San Francisco Opera in the 1950s, as well as a contemporaneous

one for Leyla Gencer that will appear on this website later this month, it

struck me that Adler had developed what in retrospect seems to be some fairly

obvious defenses against Callas cancelling her 1957 San Francisco debut season.

Adler had scheduled Callas to perform two parts, Lady

Macbeth in Verdi’s “Macbeth” and the title role in Donizetti’s “Lucia di

Lammermoor”. There are not ever a great number of divas that sing these two

roles (and almost none that sing both). But there was a great Lady Macbeth in

1957 besides Callas, and that was Leonie Rysanek, who had just made a studio

recording of the role with the reigning Macbeth, Leonard Warren. There was also

an important rising star that was preparing the role of Lucia for performances

in Trieste later that year, to be conducted by a conductor associated with the

San Francisco Opera. That Lucia-to-be was Leyla Gencer.

Rysanek was engaged to open the 1957 season on

September 17th in the title role of Puccini’s “Turandot”. After that set of performances,

she was scheduled to rehearse the San Francisco premiere production of Strauss’

“Ariadne auf Naxos”.

Leyla Gencer had been engaged as Violetta in Verdi’s

“La Traviata”, opening September 19. Her assignments for the rest of September

consisted of student matinee performances of that opera, requiring her to be

there during the entire time that Callas was to be there. Those early October

assignments for Gencer and Rysanek meant that there was no opportunity to leave

San Francisco, so that they would be around when the tours of Los Angeles and

San Diego were to begin in late October.

Callas was to sing her first Lucia on September 27 and

her first Lady Macbeth on October 11. When she did not appear for rehearsals of

“Lucia”, Adler fired her. He did not need to search the world for a replacement

for Callas as Lucia, because Gencer was there, nor did her have to search for a

Lady Macbeth, because Rysanek was there. I suspect that there was never an

explicit agreement that either artist was covering Callas, but

they were international artists, and both knew exactly which roles they shared

with the temperamental diva.

So, it appears to me that Adler had “Callas-proofed”

his season very effectively. It also appears to me that he had NOT

“Stella-proofed” it. When Antonietta Stella’s emergency surgery required

cancellation of her scheduled performances of Amelia in Verdi’s “Ballo in

Maschera” and the title role in Verdi’s “Aida”, this created a real crisis for

Adler. Rysanek rose above the line of duty by adding two additional

performances – her German-language Amelia and an Aida, and Leontyne Price’s

star also rose in the firmament when she took on two performances of the latter

opera in San Francisco and one on the Los Angeles tour.

However, the longer-term solution to Stella’s

emergency operation was engaging Herva Nelli to complete Stella’s obligations

as Aida and Amelia, including the Southern California tour. The tour had been

scheduled to perform in San Diego on two nights a week apart – with Gencer

singing Violetta and Callas singing Lucia. Callas’ cancellation and replacement

by Gencer meant that San Diego would have two separate visits by the Turkish

diva.

The spacing of Gencer’s performances would have

permitted her to have performed in a San Diego “Lucia”, and, judging from her

spectacular performance as Lucia that I saw three days later at the Shrine

Auditorium, it almost certainly would have been a great success. However, the

disappointed ticket-holders had expected Callas, and having an unknown name

(Gencer was not a household word in Southern California in 1957, and most of

the other remaining members of the “Lucia” casts were relatively unknown) twice

in a week’s time for the only two performances of San Francisco Opera in San

Diego that year, surely had to have bothered the promoters in that tour city.

The promoters likely slept easier when offered the

prospect of replacing the “Lucia” with a performance of Verdi’s “Aida” that

would have at least three familiar names to the San Diego audience – soprano

Herva Nelli in the title role, the superb mezzo-soprano Blanche Thebom as

Amneris, and veteran basso Nicola Moscona as Ramfis. All three had been

stalwarts at the Metropolitan and San Francisco Operas. Nelli’s star turn in

five Toscanini NBC Orchestra performances were among the early LP recordings of

complete operas. Unfortunately, neither the tenor, Eugene Tobin, nor the

baritone, Umberto Borghi brought any star power, and the latter did not even

bring good performance reviews from his efforts earlier in the season.

Looking at the situation retrospectively, I, of

course, would have wished that Nelli, whose voice to me never really seemed

right for Aida, would have switched the Los Angeles and San Diego Aidas with

Leontyne Price, who had a perfect voice for the role. But in September 1957

Price was no better known than Gencer, and Nelli was at least a Callas

substitute of whom many people had heard.

The singers generally met the audience’s expectations.

This was the only time that I had a chance to hear Nelli, Thebom and Moscona in

live operatic performance, and I am happy to have heard them. It is a consoling

thought that I was to see Price in “Aida” and most of her other great Verdi

roles over the next three decades.

But whatever quantities of thought went into who would

sing the roles, apparently a lesser amount went into how they would stage this

iconic grand opera in the Fox Theatre. The most vivid memory of the staging was

the triumphal march, which consisted of nine spear-carrying men walking

diagonally across the stage, circling, then walking off the opposite side.

As noted elsewhere in this website, it is my plan to

attend a performance somewhere in the world of each opera whose 50-year

anniversary I am observing. For “Aida”, I have scheduled a return to San Diego

in April, 2008 to observe the San Diego Opera’s revival of their production

directed by Garnett Bruce in what I expect will be a more appropriate staging

than what San Francisco Opera cobbled together for San Diego 50 years ago.

As a personal note, not only did the San Francisco

Opera’s tours to San Diego provide my first opportunity to see Verdi’s “La

Traviata”, “Aida” and “Otello”, but the San Diego Opera’s Verdi Festivals

during the year’s between 1979 and 1985 were the place where I saw six other

Verdi operas for the first time, for a total of nine first seen in San Diego.

The San Francisco Opera tour to the Los Angeles Shrine

Auditorium, resulted in my first performance of a tenth, with an 11th performed

by the Los Angeles Opera at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. San Francisco Opera

introduced me to 11 other Verdis at the War Memorial, so, with another first at

the Met in New York City, I have seen 23 Verdi operas, 22 for the first time in

California, each with great international casts.

Since I regard “Jerusalem” as a redo of “I Lombardi”

and “Aroldo” as a redo of “Stiffelio”, I count only 26 Verdi operas total. Any

opera company planning future performances of “I Due Foscari”, “La Battaglia di

Legnano” and “Alzira” should alert me, as I would be very interested in bagging

all three of those also.

https://operawarhorses.com/2007/05/16/callas-fired-an-opera-changed-s-f-operas-aida-at-the-fox-november-7-1957/