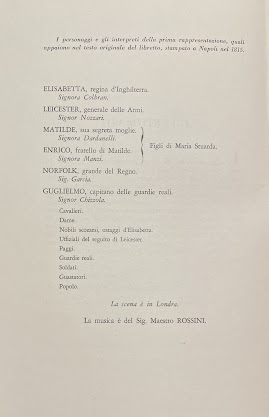

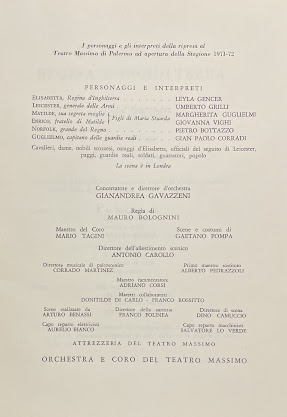

ELISABETTA, REGINA D'INGHILTERRA

Primo maestro sostituto / First Substitute Teacher: Alberto Pedrazzoli

Maestri collaboratori / Collaborating Directors: Donitilde Di Carlo, Ignazio Garsia, Giuseppe Grassodonia, Franco Rossitto

Choreogrfie / Choregraphy: Ugo Dell'Ara

Maestro rammentatore / Prompter: Adriano Corsi

Direttore dell’allestimento scenico / Director of Stage Design: Antoni Carollo

.jpg) |

| Gaetano Pompa, Leyla Gencer, Mauro Bolognini |

Rappresentazioni:

Palermo, Teatro Massimo – 9 dicembre 1971.

Interpreti: Leyla Gencer, Umberto Grilli, Margherita Guglielmi, Giovanna Vighi, Pietro Bottazzo, Gian Paolo Corradi.

Scene e costumi: Gaetano Pompa.

Direttore: Gianandrea Gavazzeni.

Tournée complessi artistici del Teatro Massimo di Palermo : 4- 7- 9 settembre 1972 al Festival Internazionale di Edimburgo.

Interpreti principali : Leyla Gencer, Umberto Grilli,Margherita Guglielmi, Pietro Bottazzo, Gian Paolo Corradi.

Scene e costumi : Gaetano Pompa

Direttore : Gianandrea Gavazzeni

Sono passati ormai quindici giorni da quando mi trovai all’improvviso al buio tra le solenni sale e i misteriosi corridoi del Teatro Massimo di Palermo. Ero là per assistere alla prima ripresa nel nostro secolo dell’”Elisabetta” di Rossini, ed ebbi a primo colpo l’impressione d’aver sbagliato opera. Ero infatti sempre in Rossini, ma in piena “scena delle tenebre”, come s’incontra nel “Mosè”. Poi, mi spiegarono che non era stato il Patriarca davanti al Faraone, ma un neo-profeta del sindacalismo di fronte al Barone, cioè al sovrintendente De Simone; e che l’intervento non era del cielo, ma delle masse: insomma, neo-umanesimo. Si trattava difatti d’uno sciopero rigorosamente rispettoso degli orari. Ad ogni modo son quindici giorni: l’opera non s’è ancora data, la stagione non s’è ancora aperta, e, se ho capito bene, ogni sera là scende puntuale il buio: sul teatro e sulle speranze di chi aspetta questo benedetto Rossini.

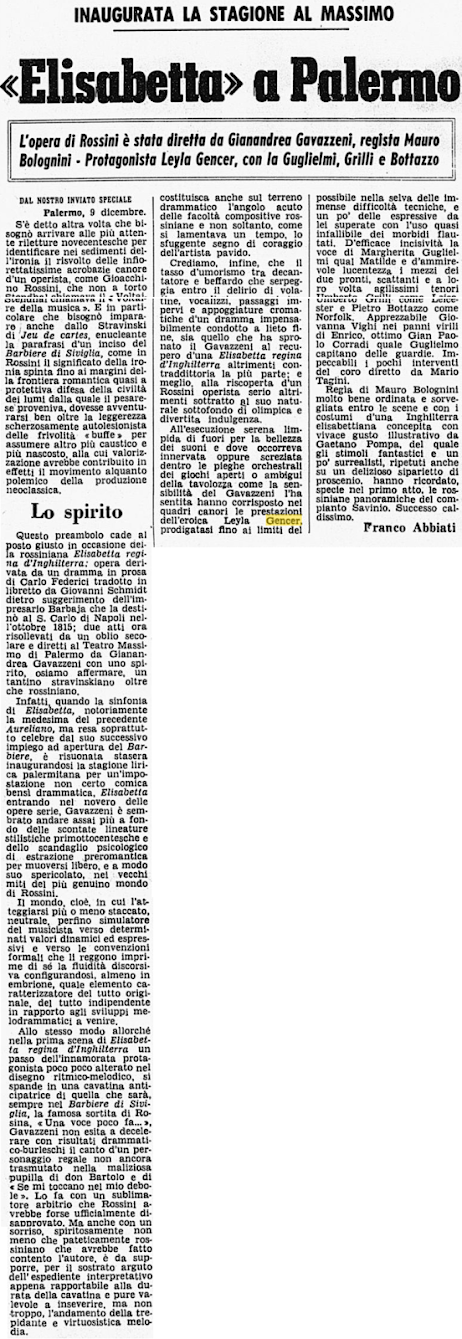

Estratto da “Corriere della sera” di venerdì 10 dicembre 1971 (di Franco Abbiati)

All’esecuzione serena, limpida di fuori per la bellezza dei suoni e dove occorreva innervata oppure screziata dentro le pieghe orchestrali dei giochi aperti o ambigui della tavolozza come la sensibilità del Gavazzeni l’ha sentita hanno corrisposto nei quadri canori le prestazioni dell’eroica Leyla Gencer, prodigatasi fino ai limiti del possibile nella selva delle immense difficoltà tecniche, e un po’ delle espressive da lei superate con l’uso quasi infallibile dei morbidi flautati. D’efficace incisività la voce di Margherita Guglielmi qual Matilde e d’ammirevole lucentezza i mezzi dei due pronti, scattanti e a loro volta agilissimi tenori Umberto Grilli come Leicester e Pietro Bottazzo come Norfolk. Apprezzabile Giovanna Vighi nei panni virili di Enrico, ottimo Gian Paolo Corradi quale Guglielmo, capitano delle guardie. Impeccabili i pochi interventi del coro diretto da Mario Tagini.

Regista dell’opera è Mauro Bolognini.

Un'avvincente

Al Teatro Massimo di Palermo è tornata sulle scene dopo centotrentasette anni «Elisabetta regina d'Inghilterra» di Gioacchino Rossini. La qualità dell'opera è stata messa in piena luce grazie al livello dell'esecuzione diretta da Gianandrea Gavazzeni con la regia di Bolognini. Leyla Gencer protagonista nelle vesti della grande sovrana cinquecentesca

↓ Photo: Un bozzetto per la scena del primo atto di « Elisabetta regina

d'Inghilterra ». E' opera del pittore Gaetano Pompa, alla sua prima esperienza

nella scenografia teatrale

Palermo, dicembre

Dicembre 1971: Elisabetta regina d'Inghilterra di

Gioacchino Rossini torna sulle scene dopo 137 anni di totale oblío. Rappre

sentata infatti al « San Carlo» nel 1815 e poi saltuariamente ripresa nella

prima metà dell'Ottocento, l'opera è letteralmente scomparsa dal repertorio per

ritrovare ora al « Massimo» di Palermo una luminosa affermazione dopo un sonno

più che secolare.

↓ Photo: La regina Elisabetta e Matilde, la sua giovane

rivale, in un momento dell'opera rossiniana. Le interpreti sono Leyla Gencer e

Margherita Guglielmi

... un genio istintivo alla Bellini e alla Donizetti che

poteva magari concedersi anche qualche vacanza dello spirito. Il pesarese,

dotato oltre tutto di ferratissimo mestiere e di una mozartiana qualità

musicale, fallì ben pochi bersagli. Per questo il prolungato silenzio sulla sua

figura (la cui conoscenza era circoscritta, fino ad un ventennio fa, a non più

di tre o quattro opere) rimane tra le gravi carenze della nostra cultura; ad

esse tardivamente si è cercato di riparare dall'ormai storico Maggio Fiorentino

del '52.

↓ Photo: Dietro le quinte dello spettacolo di

Palermo: da sinistra il regista Mauro Bolognini, Leyla Gencer, lo scrittore

Riccardo Bacchelli e il direttore d'orchestra Gianandrea Gavazzeni. Gli altri

interpreti principali dell'opera erano Margherita Guglielmi, Piero Bottazzo,

Umberto Grilli

↓ Photo: Ancora Leyla Gencer nelle vesti di

Elisabetta sul palcoscenico del Teatro Massimo. Subito dopo la « prima »

palermitana i dirigenti del Festival di Edimburgo hanno scelto l'opera di

Rossini per la prossima edizione della manifestazione. «Elisabetta regina

d'Inghilterra» fu rappresentata la prima volta a Napoli nel 1815

.... nitivamente i giudizi restrittivi degli specialisti

rossiniani, probabilmente suggestionati dallo stesso autore che non la tenne in

gran conto. Forse Rossini come ha supposto in un'intervista Riccardo Bacchelli

- non amava essere considerato un cinico e un manipolatore, incline a

sfruttare, per occasioni diverse, pagine musicali già composte. E nell'Elisabetta

figurano alcuni brani musicali dall'ouverture, tratta a sua volta

dall'Aureliano in Palmira, alla cavatina della protagonista che diventerà

quella di Rosina - che saranno testualmente ripresi nel Barbiere. Cert'è però

che, a prescindere dalle sue prevenzioni, proprio per il primo impegno

napoletano - il « San Carlo» allora era un teatro di punta, dotato di

un'orchestra di prim'ordine - Rossini volle offrire un lavoro molto elaborato,

anche sotto il profilo strumentale: il « tedeschino », come lo chiamavano allora,

conquistò il pubblico partenopeo, esibendo tutta la propria «dottrina»

compositiva.

Principal characters:

Elisabetta, Queen

of England (soprano)

LIBRETTO by

Giovanni Federico Schmidt

COMPLETE RECORDING

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)