ELISABETTA, REGINA D'INGHILTERRA

* Nota: La stagione lirica 1970-71 si sarebbe dovuta inauguare il 26 novembre 1970 con l'opera Elisabetta Regina d'Inghilterra di Rossini. Pero la Recita inauguare e stata sospesa per lo sciopero dei lavoratori de Teatro, che protrattosi sino al 12 dirembre, l'opera di Rossini non venne rappresentata. Conseguentemente, la stagione si e inaugurata con il Fidelio, secondo opera del cartellone.

Recording of the opera is from the general rehearsal.

Stage director: Mauro Bolognini

Scene and costumes: Gaetano Pompa

Primo maestro sostituto / First Substitute Teacher: Alberto Pedrazzoli

Maestri collaboratori / Collaborating Directors: Donitilde Di Carlo, Ignazio Garsia, Giuseppe Grassodonia, Franco Rossitto

Choreogrfie / Choregraphy: Ugo Dell'Ara

Maestro rammentatore / Prompter: Adriano Corsi

Direttore dell’allestimento scenico / Director of Stage Design: Antoni Carollo

Matilda his secret wife SYLVIA GESZTY soprano

The Duke of Norfolk PIETRO BOTTAZZO tenor

Enrico (Henry) Matilda’s brother WILLIAM BORELLI mezzo-soprano

Guglielmo (Fitzwilliam) Captain of the Royal Guard GLAUCO SCARLINI tenor

ELISABETTA REGINA D’INGHILTERRA di Gioachino Rossini

“La rappresentazione di “Elisabetta regina d’Inghilterra” può essere una grossa sorpresa, una sorpresa per tutti coloro che non l’hanno mai ascoltata e nello stesso tempo motivo di rimorso per noi che non l’abbiamo fatta. Da parte mia ne sono entusiasta. Ritengo che l’opera avrà una certa ripercussione se non altro per la musica”. Così si è espresso il maestro Nino Sanzogno sul “dramma in musica” di Rossini che dovrebbe dirigere (scioperi delle masse permettendo) domani sera in occasione dell’apertura della stagione lirica 1970-71 del Teatro Massimo di Palermo. E’ la prima volta in questo secolo che l’opera viene rappresentata in Italia. Rossini la scrisse nel 1815 per il San Carlo di Napoli. In occasione della prima, anzi, la parte della protagonista fu interpretata da Isabella Colbran, il celebre soprano del tempo che doveva poi diventare la sposa del maestro.[…] Il musicologo Rognoni, in un suo libro dedicato a Rossini, sostiene che l’opera “costituisce un radicale rinnovamento del linguaggio drammatico musicale: essa preannuncia i tempi nuovi, incontro ai quali Rossini procede, suo malgrado, bruciando in continua reazione con se stesso e col futuro una esperienza che avrebbe nutrito un intero secolo”.

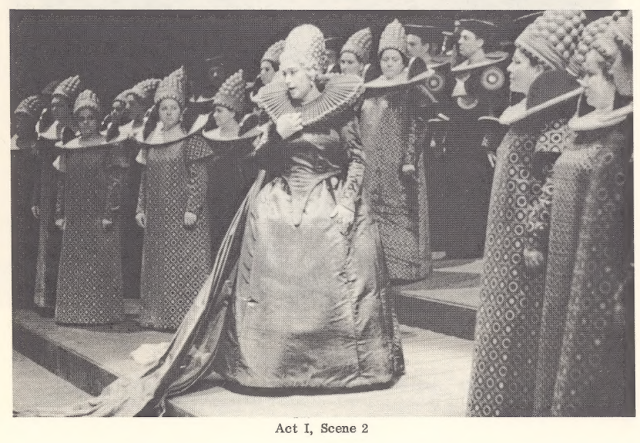

Per me, assistendo ad una prova, l’emozione era stata assai viva. L’allestimento era di rara suggestione: le scene, di Gaetano Pompa, fra nostalgie d’un Quattrocento alla Paolo Uccello e ripensamenti della lezione di un Savinio, creavano l’ambiente più adatto per la regia di Mauro Bolognini, impostata su rapporti di masse, di luci e ombre, di pochi gesti pregnanti, e chiaramente scandita sul ritmo musicale. La compagnia di canto, seguiva con perfetta coesione la limpidissima lettura impressa da Nino Sanzogno, immedesimato nell’orchestra dal suono trasparente e nella vicenda dominata con vigile equilibrio: la scattante sicurezza di Silvia Geszty, la signorilità e la bellezza timbrica di Bottazzo, la pienezza vocale di Grilli avevano fatto corona attorno a Leyla Gencer, a cui non so se il gusto di rifare la parte impervia della favolosa Colbran o la tessitura congeniale con le agilità incessanti negli acuti ha fatto trovare, accanto alle note qualità di creatrice di personaggi regali, una smagliante forma di voce.

Bene, il “giallo” continua. Quale sarà la sorte di Elisabetta? La ricerca dei colpevoli, però non mi interessa molto; tanto più che i rapporti fra la direzione e le masse, falsati dalla dissennata regolamentazione dei teatri italiani, sono complessi e valutabili con molta difficoltà a caldo: se ne potrà riparlare. Per ora ciò che preme è fare appello che Elisabetta non venga soppressa: lasciatele soltanto la possibilità di farsi intendere, adesso o nei prossimi mesi, e tutti capiranno perché.

CUMHURİYET DAILY NEWSPAPER

|

| Leyla Gencer Kraliçe Elizabeth rolünde |

PALERMO MUCİZESİ

Leyla Gencer, Kraliçe Elizabeth rolüyle parlar. Tüm eleştirmenler övgüler yarıştırır. Tüm gazeteler “Palermo Mucizesi” diye başlık atar. (Bakınız: Leyla Gencer: Tutkunun Romanı/Cumhuriyet Kitapları) Öyle başarılı olur ki bir yıl sonra, şef değişse de Leyla Gencer yine aynı rolle Palermo’dadır. Bir yıl sonra da Edinburgh Opera Festivali’nde. Bütün bunlar 1970-73 arasındadır. Sonra aradan 50 yıl geçer.

Mektubu şöyle bitiyordu: “Rolü istedim verdiler. Gencer’in tarihi Elisabetta ‘manifesto’/posteri girişte fuayede soldadır. Kontratı imzalayınca sevgi ve saygımın ifadesi olarak postere gidip selam verdim.”

İYİ Kİ SANAT VAR

“İngiltere Kraliçesi” ekim sonu ve kasım

başında Palermo’da temsil edildi. Her temsilden önce Mert Süngü seyirciye Leyla

Gencer hakkında konuşma yaptı. Her temsilden sonra Leyla Gencer’in posterine

göz kırptı. Program dergisinde fotoğraflarının peş peşe yayımlanması onu

gururlandırdı, çok mutlu etti. Şef Antonino Fogliani, rejisör Davide

Livermore idi. Elizabetta rolünü Japon mezzo soprano Aya

Wakizono üstlenmişti. Prodüksiyon olumlu eleştiriler aldı.

|

| Mert Süngü ve Elisabetta rolünde Japon mezzo soprano Aya Wakizono |

Bu eleştirilerden kimi örnekleri okuduğumda kendisi Çin’de Pekin’de Johann Strauss’un “Yarasa” operasının provalarındaydı. 2025’te ise Floransa Maggio Musicale Festivali’nde “Norma” da Pollione rolünde, Şili/Santiago’da “La Traviata” da Alfredo rolünde sahnede olacak. Sonra Tokyo’da resital. Liste böyle uzayıp gidiyor. Türkiye’de kasım ve aralıkta Mert Süngü’yü IDOB ile hem “2. Mehmet” hem de “La Traviata”da izleme fırsatımız yeniden olacak.

FROM LP BOOKLET

FROM CD BOOKLET

Stendhal, Rossini’s famous biographer, described a typical opera company in an Italian town of the time thus. “The manager is frequently one of the wealthiest and most considerable persons in the little town he inhabits. He forms a company consisting of a prima donna, tenor, basso cantante, basso buffo, a second female singer and a third bass. He engages a composer to write a new opera, who has to adapt his own airs to the voices and capacities of the company. The libretto is purchased from some unlucky son of the Muses, generally a half-starved Abbé. The next thing that usually happens is that - the manager falls in love with the prima donna; and the progress of this amour gives ample employment to the curiosity of the gossips. The company at length gives its first performance after a month of cabals and intrigues. The population does nothing but discuss the merits of the forthcoming music and singer with the eager impetuosity that belongs to the Italian climate. The first performance, if successful, is generally followed by twenty or thirty more presentations of the same piece; after which the company beaks up. This is what is called a stagione.”

When the twenty-three-year-old Rossini arrived in Naples in 1815, Isabella Colbran, the prima donna of the San Carlo Teatro was indeed the mistress of the impresario Barbaia, Rossini’s chief at that theatre - but Rossini soon changed that. Barbaia’s power and influence were considerable - fortunately for Rossini, for the Neapolitans viewed any musician who had not been trained in their own schools with the utmost suspicion. Rossini’s triumphs in Venice meant less than nothing to them. This xenophobia was rendered all the more dangerous by the intrigues of Paisiello and Zingarelli, the director of the conservatoire both of whom made a point of liking no music except their own. (Zingarelli, in conversation with Spohr, said that if Mozart had only studied a little more, he would certainly have ended by writing a good opera). Moreover, a rather different style of music from that which found favour in the north of Italy was expected by the Neapolitans, who demanded from their singers’ robustness and brilliance rather than subtlety or delicacy. And then there was Madame Colbran to be satisfied.

Isabella Colbran was born in Madrid in 1785. lt would appear that she not only had the advantage of a voice of exceptional compass bot of also of a striking dignity of movement. When Elisabetta was produced on 4th October 1815, the principal part was tailored especially to her idiosyncrasies.

Barbaia had the libretto adapted from a play which had been successfully produced in Naples in the previous year, based in this turn on an English novel called The Recess. The story is, of course, totally unhistorical. Yet Colbran is said to have looked magnificent in her sixteenth century costume and the whole of Naples raved about her beauty and talent. And that was the most important thing. Stendhal and others wrote that her voice began to give serious warning of deterioration about the year of Rossini’s introduction into her life, but she continued to sing until 1822 when she was thirty-seven. Her penchant for grand, tragic roles led Rossini to compose only one true comic opera between La Cenerentola (composed for Rome in 1817) and Le Comte Ory (1828, written for Paris in Rossini’s post-Colbran, post-ltalian period).

Through Rossini had been in Naples during the entire summer and Elisabetta was not performed until October, its actual production and composition seem to have been undertaken in a hurry. He adapted the overture of Aureliano in Palmira for the new opera and used a combination of the crescendo subject and a passage of the quartet from La Scala di Seta for the Act I finale. (He subsequently used a passage from Elisabetta’s entrance aria for Rosina’s “Una voce poco fa”). The orchestral prelude to the prison scene in Act Il was borrowed from Ciro in Babilonia. As he had an excellent orchestra at this disposal, Rossini not only produced a score decidedly more elaborate than usual, but, for the first time provided the recitatives with instrumental accompaniment. More important still, his was the first occasion on which he wrote out in full all the embellishments to be sung by the singers. He is said to have decided to do this after hearing Velluti’s exploits in Aureliano, which had made the music almost unrecognizable. The fact that he was successful in getting his way would seem to argue an exceptional degree of understanding between himself and Colbran.

The other singers available to him were equally resplendent.

Normally one would have expected Norfolk to be cast as a baritone, but - unlike the situation at present - Naples at that time enjoyed a plethora of superb tenors.

The Plot

The first scene is at the Royal court in London. Norfolk, William and courtiers are awaiting the arrival of the Queen who is to bestow honours on her favourite, the Earl of Leicester for his valour and victory in the battle against Scotland. Norfolk is seething with envy and plots against his friend, the Earl.

Unknown by all, Leicester has married Mathilda, a young girl he met while in Scotland. At the time believed her to be the daughter of a shepherd; however, he later learned that she actually is a daughter of Elisabeth’s greatest threat to the throne, Mary, Queen of Scots and has been living incognito with her brother, Henry. Leicester is now torn between love and duty and is forced to keep his marriage a secret from the jealous Elisabeth. He therefore returns to London without his bride.

Mathilda, however, has disguised herself as a prisoner of war and, accompanied by her brother, joins the hostages that are to be assimilated into the English court as pages in order to be near her husband. During the ceremony of honouring Leicester’s victory, the hostages are presented to the Queen and Leicester immediately recognizes his wife and brother-in-law among them. He is almost overcome by fright and anger. Later, when the festivities have been concluded and the Queen and assembly retire, Leicester seeks out Mathilda and Henry and chastises them for jeopardizing their position. If the Queen discovers that her favourite has not only married, but has actually married the daughter of Mary Stuart, the danger is acute. Having to confide in someone for advice, Leicester tells his story to the Duke of Norfolk, who slyly offers comfort and assistance and then immediately runs to the Queen with his story. Naturally the Queen is shocked and deeply hurt. This hurt soon turns to fury and she vows to make both Leicester and his wife pay for this treachery. She summons the court, hostage and Leicester to be present for a special gift to be bestowed upon the hero of the war. When all are present, she explains that she has decided to offer an ultimate gift to the Earl of Leicester for his service to the crown. Elisabeth then brings forth a cushion on which are placed the crown and sceptre and announces that she offers this highest to Leicester, to be her consort and King. Leicester is struck speechless, and Mathilda and Henry are visibly shaken. When Leicester turns his back on the Queen she flies into a rage and orders the guards to take the traitors to prison where they shall their deaths. The crowd is stunned at this turn of events and the act ends in a blazing finale.

Act Two opens on a room of the palace where Norfolk is wondering what he should do to obtain the position he desire.

When he seeks audience with the Queen he is refused and leaves, greatly disturbed. The Queen then enters, and bids William bring Leicester and Mathilda before her. First Mathilda is brought, and Elisabeth approaches her with controlled politeness saying that she wishes to save Leicester's life but can only do it if Mathilda will agree to have their marriage annulled. Mathilda breaks into tears and after Elisabeth warns her that her patience is limited, she signs the document. Leicester is then brought in and Elisabeth tells him that he also must sign to save his life.

Leicester refuses and the Queen sweeps out of the room.

The next scene is at the prison where crowds have gathered to bemoan the fats of their hero Leicester. Norfolk approaches and is further irritated to see how much the people love the Earl when he seizes upon the idea of using them to his advantage. Feigning grief for his beloved friend, he arouses such feelings of resentment in the crowd towards the throne’s decree of death that he persuades them to aid him in Leicester's escape. He hopes to bungle the escape, hasten Leicester’s death and become a hero himself. He tells the crowd to await his sign and enters the prison to prepare the Earl for the escape. He orders the crowd to await his signal and enters the prison to prepare the Earl for escape. He approaches Leicester as the most beloved friend and tells him of his plan of escape for

him, Mathilde and Henry.

Leicester is horrified at the prospect, saying that although he is only guilty of love, he will not lend credence to his accused act of treason by escaping. Suddenly the prison door is opened, and Elisabeth enters. Both Norfolk and Leicester are astonished and Norfolk hides behind a pillar. Elisabeth informs Leicester that the law has condemn him to die for treason and that the Queen has approved the sentence. She, however, has not come in her function as Queen but as Elisabeth who loves him and offers to aid him in escape. Leicester begs her forgiveness but again refuses to dishonour the throne by escape. At this point Henry and Mathilda have been ushered through a door in the back and warn the Queen that Norfolk has just drawn his sword. Norfolk rushes toward the Queen but is disarmed before he can strike. In gratitude, Elisabeth renounces her love of Leicester and pardons the trio. The raving Norfolk is led away by guards to another part of the prison.

The present performance was recorded at the dress rehearsal of a production planned in Palermo. A strike prevented the premiere taking place, and the opera was not staged until one year later. Margherita Guglielmi took over from Sylvia Geszty, who had other commitments at the time, and the opera was conducted by Gavazzeni who stepped in for Sonzogno.

FROM LP BOOKLET