GERUSALEMME

|

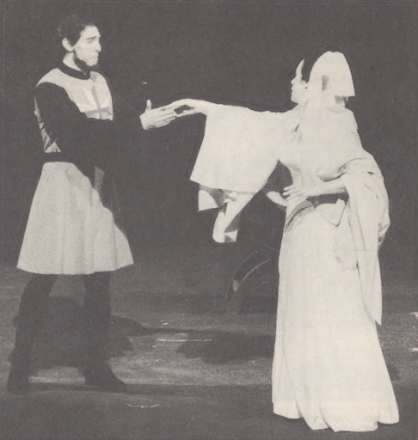

| Elena / Figurino |

|

| Elena / Figurino |

|

| Donna del Popolo / Figurino |

|

| Ambasciatore / Figurino |

|

| Ambasciatore / Figurino |

|

| Ufficiale dell'Emiro / Figurino |

|

| Seguito del Conte di Tolosa / Figurino |

|

| Conte di Tolosa / Figurino |

|

| Conte di Tolosa / Figurino |

|

| Araldo / Figurino |

– Mais pourquoi se consacrer à l’art lyrique ?

– C’est un vieil ami, un goût que je n’ai jamais pu

satisfaire, faute de temps. J’ai toujours aimé la musique ; j’en ai même fait –

du violon – quand j’étais enfant ; jeune homme, j’ai joué dans un orchestre de

jazz et depuis six mois, je ne lis que des partitions d’opéra.

Combat, 1er octobre 1963

Maintenant qu’il est parti du TNP, Jean Vilar peut se consacrer exclusivement à son métier de metteur en scène. Ses préoccupations de directeur et d’administrateur, qui ont été les siennes pendant douze ans, l’avaient contraint à refuser de nombreuses sollicitations extérieures. Parmi elles, la mise en scène lyrique. En 1952, il décline Médée, à Florence, spectacle qui voit éclore une nouvelle cantatrice, Maria Callas.

|

| L'émir, Gerusalemme, maquette de costume Léon Gischia, 1963, fonds association Jean Vilar © Adagp, Paris, 2023 |

|

| Un officier de l'émir, Gerusalemme, 1963, fonds association Jean Vilar © Adagp, Paris, 2023 |

COMPLETE RECORDING

FROM LP BOOKLET

FROM CD BOOKLET

Gerusalemme

Non esiste, a tutt’oggi, una monografi asıl rapporti

artistici di Verdi con la Francia, il Paese che, nel freudiano legame di

amorodio, ha svolto un ruolo protagonistico nella carriera del Nostro.

Gerusalemme

There still does not exist a monographic study that

deals with the artistic association between Verdi and France, that country

which, in a love-hate relationship, played a protagonist's role in the Italian

musician's career.

FROM CD BOOKLET

|

I LOMBARDI ALLA PRIMA CROCIATA

|

GERUSALEMME

|

|

ATTO I / ACT I |

ATTO I / ACT I |

|

Preludio (in Mi bem. Magg.)

|

Preludio (in Mi min.) [RIFATTO]

|

|

Introduzione e scena a concertato:

|

Duettino Elena, Gastone [NUOVO]

|

|

Coro "O nobile esempio"

|

Preghiera di Elena. Il levar del sole [NUOVO]

|

|

Coro di Claustrali; scena, aria di Pagano e Coro

Sgherri

|

[corrisponde con modifiche alla Introduzione]

|

|

Scena e Preghiera di Giselda

|

Coro di Claustrali; scena, aria Ruggero.

|

|

Scena e finale I.

|

Coro Sgherri e cabaletta Ruggero. Scena e finale I.

|

|

ATTO II / ACT II

|

ATTO II / ACT II

|

|

Coro di Ambasciatori

|

Gran scena Ruggero

|

|

Scena e Cavatina Oronte:

|

Scena e Polacca di Elena (in Fa Magg.)

|

|

"La mia letizia infondere" (in La Magg.)

|

Coro "Oh mio Dio! Dunque vano è il tuo

pegno?"

|

|

Gran scena Pagano e Marcia de' Crociati.

|

Gran Marcia [NUOVO]

|

|

Duettino Arvino-Pagano e Inno de' Crociati

|

Terzetto (dei bassi) [NUOVO] e Coro "Sommo

Iddio"

|

|

Coro di Schiave

|

Scena e Cavatina Gastone "Ch'io possa udir

ancora"

|

|

Rondò - Finale secondo Elena.

|

[SOPPRESSA LA CABALLETTA]

|

|

Duetto Elena, Gastone.

|

|

|

ATTO III / ACT III

|

ATTO III / ACT

III

|

|

Coro della Processione "Gerusalem!"

|

Coro di Schiave

|

|

Scena e duetto Giselda-Oronte

|

Ballabili Grande aria Elena, arrivo dei Crociati,

Rondo.

|

|

Scena ed aria Arvino

|

Marcia funebre [NUOVA]

|

|

Preludio e Terzetto-Finale terzo

|

Grande scena della Degradazione.

|

|

Giselda, Oronte, Pagano.

|

Aria Gastone [NUOVA] Finale [NUOVO]

|

|

ATTO IV / ACT IV

|

ATTO IV / ACT IV

|

|

Visione Coro, Giselda, Oronte

|

Coro "Gerusalem!"

|

|

Aria "Non fu sogno" Giselda (Polacca in Fa

Magg.)

|

Scena e Terzetto Elena, Gastone, Ruggero

|

|

Coro "O signore, dal tetto natio"

|

[SOPPRESSA INTRODUZIONE VIOLINO SOLO]

|

|

Scena, Inno di guerra e Battaglia

|

Battaglia. Scena e quintetto. Inno finale.

|

|

Scena, Terzettino Giselda, Arvino, Pagano ed Inno

finale.

|

Jérusalem viene portata in Italia, naturalmente nella

lingua del pubblico come allora era consuetudine, affidata all'Editore Ricordi:

Gerusalemme, versione ritmica dal francese di Calisto Bassi, arriva alla Scala

il 26 dicembre 1850, intatta rispetto all'originale come Verdi esige

dall'Editore, coi soli ballabili soppressi. Alla Fenice di Venezia l'opera

viene rappresentata l'11 febbraio 1854. Successivamente l'altra opera (cioè la

matrice primigenia dei Lombardi) prosegue il suo cammino indipendente anche in

Francia e approda in versione francese (Les Lombards à la première Croisade) a

Parigi il 10 gennaio 1863. La ripresa di Gerusalemme nel nostro secolo avviene

al Teatro La Fenice di Venezia il 24 settembre 1963. La Fenice di Mario Labroca

e Floris Ammannati punta in grande sull'avvenimento, combina le componenti

dello spettacolo in base al loro potenziale di accensione sul primo Verdi. Si

opta per la versione italiana, la più naturale in quella fase di

riappropriazione; solo più tardi, sui dati e il gradimento dell'avvenuto

recupero, interverrà la filologia dell'originale (Jérusalem). Il direttore

Gianandrea Gavazzeni è personaggio di punta, poiché negli orizzonti musicali

del Novecento, ha tracciato le coordinate dei nostri interessi operistici,

secondo un ventaglio di aperture culturali e di prospettive teatrali ormai

irrinunciabili, dal Donizetti lombardo al grand-opéra, dalla risonanza storica

dell'opera russa alla concretezza declamatoria dell'opera verista. Impeto

gagliardo e congenialità con la sintesi verdiana di tinta e azione lo fanno

direttore verdiano, moderno, capace di rispondere con immediatezza vertiginosa

alle accensioni della partitura ma anche di illuminarla nella prospettiva

culturale che la distanza, oggi, consente.

I Lombardi alla prima Crociata, first performed at La Scala on the 11th February 1843, belongs to Verdi's prolific early period, which so dramatically widened and updated the scope of opera. Temistocle Solera's passionate libretto is a contraction of the homonymous poem by Tommaso Grossi, which appeared in 1824. On the 26th November 1847, at the Académie Royale de Musique in Paris, a performance was given of Jérusalem, a re- working of I Lombardi with a new libretto in French by Alphonse Royer and Gustave Vaëz. The plot was revised and simplified: the background was still that of the Crusades, but the first act was set in Toulouse instead of Milan; the other three acts were still set in Palestine, and the oriental touch was maintained by the substitution of Acciano by the Emir of Ramla. The character descriptions were altered, the action was generally clearer and the dramatic motivation more thoughtful. Ruggero (bass, previously Pagano), loves his niece Elena (soprano, previously Giselda) and hates her fiancé Gastone (tenor, previously Oronte), not her father (his own brother) the Count of Toulouse (baritone, previously Arvino, a tenor role). On the whole, the plot remained the same, except for the accusation made by the hired killer (paid by Ruggero) against Gastone who is thus banished and excommunicated. Having taken refuge in Palestine and been imprisoned by the Emir, Gastone is then discovered with Elena, recognised by the Crusaders and stripped of his knightly honours. Ruggero (who has become a hermit in Palestine) repents, thus leading to a happy ending; he frees Gastone who is victorious in combat, and who, having cleared his name, can marry Elena. The music was basically that of I Lombardi but was rearticulated round the altered plot (sections were moved and reshuffled, and the score re-worked in various places) with several episodes suppressed and new ones specifically written for Jérusalem. The result was a new opera, with a more compact structure, in which the contrasts between war-like vehemence and melodic distension were, in the spirit of grand opera, stressed, while the composer's increased maturity resulted in the characters having greater coherence and dramatic subtlety and in the loss of many rough edges. A schematic comparison of the structure and episodes of the two operas (not taking into account the modifications) will serve to highlight the differences.

|

I LOMBARDI ALLA PRIMA CROCIATA

|

GERUSALEMME

|

|

ATTO I / ACT I

|

ATTO I / ACT I

|

|

Preludio (in Mi bem. Magg.)

|

Preludio (in Mi min.) [RIFATTO]

|

|

Introduzione e scena a concertato:

|

Duettino Elena, Gastone [NUOVO]

|

|

Coro "O nobile esempio"

|

Preghiera di Elena. Il levar del sole [NUOVO]

|

|

Coro di Claustrali; scena, aria di Pagano e Coro

Sgherri

|

[corrisponde con modifiche alla Introduzione]

|

|

Scena e Preghiera di Giselda

|

Coro di Claustrali; scena, aria Ruggero.

|

|

Scena e finale I.

|

Coro Sgherri e cabaletta Ruggero. Scena e finale I.

|

|

ATTO II / ACT II

|

ATTO II / ACT II

|

|

Coro di Ambasciatori

|

Gran scena Ruggero

|

|

Scena e Cavatina Oronte:

|

Scena e Polacca di Elena (in Fa Magg.)

|

|

"La mia letizia infondere" (in La Magg.)

|

Coro "Oh mio Dio! Dunque vano è il tuo

pegno?"

|

|

Gran scena Pagano e Marcia de' Crociati.

|

Gran Marcia [NUOVO]

|

|

Duettino Arvino-Pagano e Inno de' Crociati

|

Terzetto (dei bassi) [NUOVO] e Coro "Sommo

Iddio"

|

|

Coro di Schiave

|

Scena e Cavatina Gastone "Ch'io possa udir

ancora"

|

|

Rondò - Finale secondo Elena.

|

[SOPPRESSA LA CABALLETTA]

|

|

Duetto Elena, Gastone.

|

|

|

ATTO III / ACT III

|

ATTO III / ACT

III

|

|

Coro della Processione "Gerusalem!"

|

Coro di Schiave

|

|

Scena e duetto Giselda-Oronte

|

Ballabili Grande aria Elena, arrivo dei Crociati,

Rondo.

|

|

Scena ed aria Arvino

|

Marcia funebre [NUOVA]

|

|

Preludio e Terzetto-Finale terzo

|

Grande scena della Degradazione.

|

|

Giselda, Oronte, Pagano.

|

Aria Gastone [NUOVA] Finale [NUOVO]

|

|

ATTO IV / ACT IV

|

ATTO IV / ACT IV

|

|

Visione Coro, Giselda, Oronte

|

Coro "Gerusalem!"

|

|

Aria "Non fu sogno" Giselda (Polacca in Fa

Magg.)

|

Scena e Terzetto Elena, Gastone, Ruggero

|

|

Coro "O signore, dal tetto natio"

|

[SOPPRESSA INTRODUZIONE VIOLINO SOLO]

|

|

Scena, Inno di guerra e Battaglia

|

Battaglia. Scena e quintetto. Inno finale.

|

|

Scena, Terzettino Giselda, Arvino, Pagano ed Inno

finale.

|

Jérusalem appeared in Italy, in the audience's

language as was usual at the time, courtesy of the publisher Ricordi:

Gerusalemme, translated from French by Calisto Bassi, was premiered at La Scala

on the 26th December 1850. Verdi had insisted on Ricordi making no

alterations in respect of the original version, except for the omission of the

dances. The opera was performed at La Fenice in Venice on the 11th February

1854. Over the next few years, the other opera (i.e. the earliest version of I

Lombardi) continued to be performed, appearing in France, with a version in

French (Les Lombards à la première Croisade) being staged in Paris on the 10th

January 1863. The re-appearance of Gerusalemme in this century took place at

the Teatro La Fenice in Venice on the 24th September 1963. La

Fenice, then in the hands of Mario Labroca and Floris Ammannati, pulled out all

the stops for the event, exploiting the capacity of each of the production's

elements to throw light on the early Verdi. They chose to perform the Italian version,

the appropriate choice at these years; only later, once the success of the

re-discovered opera was assured, did the original language re-appear

(Jérusalem). The conductor Gianandrea Gavazzeni is a key figure in the world of

20th century music, having helped to stimulate the public's interest in opera,

directing it towards a wide range of cultures and theatrical perspectives, from

the lombard Donizetti to grand opera, from the historic power of the Russians

to the explicit rhetoric of "opera verista". Gavazzeni's strength and

impetus and his understanding of Verdi's special blend of action and emotion

make him the ideal Verdi conductor: he has the capacity to respond with

startling immediacy to the score's provocations, and yet at the same time can

step back and see the whole thing from the distance of today's cultural

viewpoint.