Caterina Cornaro was one of those grand Renaissance ladies whose lives prove that truth can be not only stranger than fiction, but more exotic than Italian opera. She was born in Venice in 1454 and at the age of fourteen was contracted to marry James de Lusignan, the illegitimate son of King John II of Cyprus. James, who had seized power in Cyprus on the king's death while the succession was in dispute, desperately needed the support of Venice, which his marriage to Caterina ensured. In 1472, at the age of eighteen, Caterina left Venice for Nicosia with the title of Queen of Cyprus, Jerusalem and Armenia. James died within the year—not, as in the opera, in battle, but from natural causes—leaving his kingdom to Caterina and their child, as yet unborn. Soon after the birth of her son there was a revolution which resulted in imprisonment for Caterina, but she was soon released by a Venetian force sent to restore order to the island. In 1488 another royal wedding was planned for Caterina—to the King of Naples. This was too much for the republican government of Venice, which promptly decided to recall Caterina and take formal possession of Cyprus for itself. Caterina, who had developed a taste for royal life, tried to resist, but she was finally compelled to abdicate and return to Venice. In compensation she was given the castle and town of Asolo for her lifetime, and there she spent her days contentedly queening it over a small but quite brilliant court until her death in 1510. Her memory has been kept alive by Titian's portrait in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence and by at least four operas—Lachner's Catharina Cornaro, Halévy's La Reine de Chypre, Balfe's The Daughter of St. Mark and, most notably, Donizetti's Caterina Cornaro.

Caterina Cornaro was one of those grand Renaissance ladies whose lives prove that truth can be not only stranger than fiction, but more exotic than Italian opera. She was born in Venice in 1454 and at the age of fourteen was contracted to marry James de Lusignan, the illegitimate son of King John II of Cyprus. James, who had seized power in Cyprus on the king's death while the succession was in dispute, desperately needed the support of Venice, which his marriage to Caterina ensured. In 1472, at the age of eighteen, Caterina left Venice for Nicosia with the title of Queen of Cyprus, Jerusalem and Armenia. James died within the year—not, as in the opera, in battle, but from natural causes—leaving his kingdom to Caterina and their child, as yet unborn. Soon after the birth of her son there was a revolution which resulted in imprisonment for Caterina, but she was soon released by a Venetian force sent to restore order to the island. In 1488 another royal wedding was planned for Caterina—to the King of Naples. This was too much for the republican government of Venice, which promptly decided to recall Caterina and take formal possession of Cyprus for itself. Caterina, who had developed a taste for royal life, tried to resist, but she was finally compelled to abdicate and return to Venice. In compensation she was given the castle and town of Asolo for her lifetime, and there she spent her days contentedly queening it over a small but quite brilliant court until her death in 1510. Her memory has been kept alive by Titian's portrait in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence and by at least four operas—Lachner's Catharina Cornaro, Halévy's La Reine de Chypre, Balfe's The Daughter of St. Mark and, most notably, Donizetti's Caterina Cornaro.

FROM LP BOOKLET

DONIZERTTI'S CATERINA CORNARO

BY RUBINO PROFETA

Translated by Clement Dunbar

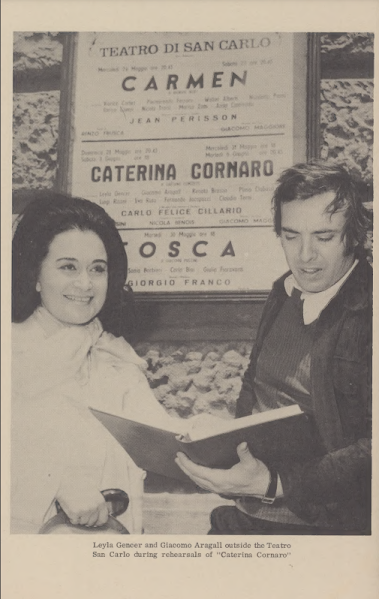

Caterina Cornaro turned out to be the last in the long catalogue of more than sixty works that Donizetti wrote for the operatic stage. Created a few months before the appearance of Don Pasquale, Maria di Rohan, and Don Sebastiano, a period of considerable productivity by the composer, it is nonetheless a little discussed work. In fact, there are not many reviews or first-hand accounts of the ill-fated first performance of January 12, 1844, on the stage of the same San Carlo opera house which has brought it before the public again today.

A few comments have, however, come down to us from several rather undetailed newspaper accounts of the time. One critic speaks of the fullness of maturity" and another speaks of "exhaustion and break-down"; and while the first description is unexceptionable, the second does not seem completely fitting or justified. It has the fullness of maturity, to be sure, but with a clearly defined movement toward a new idiom, one which would certainly have been fully apparent in the works that would have followed if fate had not so unexpectedly drained the life of the versatile composer of Lucia at the height of his career.

The story is told elsewhere of how the continual wanderings from one end of Europe to the other, and the first symptoms of the fatal disease that was soon to bring his death induced Donizetti to write repeatedly to his faithful Neapolitan friends to intercede with the management of the San Carlo to release him from the obligation of preparing Caterina Cornaro, which had been projected for the end of the 1843 season. He wrote: "In the midst of my labors I am well, and my travels are not wearing me out, but how can I go to Naples in July and then race off to Paris by August?... And from time to time there is a return of my usual fever which doesn't last more than twenty-four hours, but which leaves me dejected and exhausted..." In a later letter to his friend Tomaso Persico, he says: "What if I fall ill from hardship and overwork, like last year?... But convince them to cancel it... if they don't believe my fevers are real, I have two doctors here in Paris, Fossati and Maroncelli, ready to write a thousand certificates for me."

It is certain too that Donizetti was not eager to set Giacomo Sacchéro's libretto, and that he would have been willing to give up the undertaking if assurances had not come from Naples that the production of Cornaro would be postponed to January of the following year. And so, he set to work on it between performances of Don Sebastiano and in the midst of the triumphs of the already well-known Maria di Rohan and Don Pasquale, which had both been enthusiastically received and were then making the rounds of the major musical capitals of Europe.

Anyone who has the opportunity to inspect closely the original score of Caterina Cornaro will be aware that it was written in the shortest possible time compared with Donizetti's other works, and in odd moments and places, for he will observe the helter-skelter pages of various shapes and kinds often held together with the thinnest threads. But what genius in the hastily sketched markings; what fire, what imagination in those lines, sometimes incomplete or barely hinted at, but so rich with dramatic power, so full of the genuine lyrical vein!

We know now that Donizetti could not have attended a single one of the unfortunate performances at the San Carlo, since after the outcome of the prima he wrote a friend: "Ah, those Neapolitans, they all make me so bitter!" And then he went on: "However Caterina was performed at Naples... I hear a lot of hissing from Italy..." Not even when the opera was repeated several months later at Parma, receiving this time a uniformly favorable reception, was Donizetti present. Word was sent to him in Vienna, and to a friend who asked him if he were enjoying his revenge, he sadly replied: "Happy, yes... but I don't feel well. Always a touch of fever and headache, and an uneasiness, a restlessness... What will come of it?"

Because it is clear that the composer couldn't have been present at the first performance, one naturally wonders what the result would have been had Donizetti undertaken the musical supervision of it.In the light of the numberless errors of transcription from the original score, all faithfully copied in the various versions which were used in the preparationof the orchestral materials, there is reason to believe that the work was performed in absolutely abominable fashion. There is a long section, for example, in the very effective women's chorus in the last scene where, in Donizetti's own hand, appear the words "wrong key"! (Doubtless referring to a group of transposed instruments); well, in the versions made from the original the annotation is copied exactly without anyone ever taking the trouble to correct the error. We can imagine what great 'discords" the Neapolitan audience had to put up with on that disgraceful evening of January 12, 1844.

But the chilly reaction of the San Carlo public to Donizetti's last unfortunate creation must not have been entirely due to that; we can account for it better perhaps by looking at what the Parisian critic for the "Revue des deux mondes" wrote the morning after the prima of Don Sebastiano on the subject of the new Donizettian idiom which we spoke of earlier: "...in the cavatinas, the romanzas, and the slow and quiet pieces, we find in every note the inspiration which created Anna Bolena and Lucia; but if the situation becomes complex, if the passions become heated, if the voices combine, then farewell to the fugitive melody which takes flight and is lost in a confused jumble of sounds..." So, the "symphonic"! quality of Donizetti was not understood or accepted by the public of that time, or by the critic who more than once had rewarded Donizetti with the adjective ''Germanic."' How could they become excited by the penetrating choruses and the sweeping finales of Cornaro when they had shown themselves displeased by even the slightest contrapuntal complexities? Admittedly, Caterina Cornaro contains conventional pages that repeat situations already found in other Donizettian works of greater fame, and yet there are strong anticipations of the future dramatic idiom of Verdi to.be found in it, with several incisive passages—like the chorus of assassins—which Verdi must surely have known before creating the shadowy "conspiracy scene" in Ernani.

Sacchéro's libretto, which may seem inferior from a literary point of view, reveals uncommon gifts of essential theatricality, with scenic divisions of rare dramatic effectiveness and a clear individualization of the various characters. These elements must have attracted Donizetti, who, with his undisputable genius, succeeded in enlivening some sections with his stirring dynamism, such as the Caterina-Gerardo duet in the finale of the Prologue (whose concluding theme Donizetti had already used, even if only in embryonic form, in his earlier Parisina D' Este), or the duet for Gerardo and Lusignano in the first act, or the overwhelming ensemble in the first act finale, with its amazing inventiveness in the exposition of the theme and its unfailing development. The figure of the heroine and that of the ill-fated king are most centrally yoked, both by the regal nobility of their musical speech and by the aptness of their appearances on stage and the constant balance in the amount of dramatic utterance assigned to each. But the most striking thing in this opera is the singular and unexpected encounter with so many brilliant modulations, with such bold harmonic combinations as to make us think that they must surely have been the fruits of the incipient mental imbalance of the composer, although clearly to the contrary they were simply drawn from the logical evolutionary process in full and decisive ferment. If it were possible ever to speak of "incipient mental imbalance," it would be when speaking of the restless and disordered draft of the score, which from time to time actually contains gaps and inaccuracies; but I insist still on saying—with firm conviction and with the most profound respect and devotion for the great man from Bergamo—that those imprecisions were due not only to his pressing haste but also.to a certain unwillingness with which he set to work scoring Caterina Cornaro—an unwillingness that translated itself into a feverish anxiety when it entered into the life of the work. It is unnecessary for me to repeat here the countless difficulties which, as in previous revisions I have done, I have had to come to grips with in the course of this exhausting work. On the one hand there was the obligation to remain scrupulously faithful to the intentions of the composer, even when the notes and markings were unclear; on the other was the hope of pinpointing the problems that had contributed to the initial failure of the work, with the intention of eliminating their causes as far as possible.

I have sometimes sought to lighten the orchestration, particularly in the most confusing and disordered passages, limiting the frequent abuse of the woodwinds, especially in the more intimate segments, in order not to suffocate the melodic lines of the soloists. I had to systematize in modern notation all of the transposed instrumental ensembles, and in some way better coordinate the horn quartet, putting it in the single key of F, while maintaining the natural characteristics of the various groups of instruments in keeping with Donizetti's usual practice. I have tried to make the most out of the numerous appearances of the drums (at that time not able to make quick changes in tuning) which modern techniques have made it possible to utilize more consistently and suitably; these are techniques the composer himself would certainly not have disdained if he had had at his disposition the perfected instruments now in use. In many places I also encountered significant differences between the manuscript score and the published piano-vocal reduction. I tried to treat each case individually, now keeping an eye on this, now on that, and always keeping in mind the agile expedience of the musical dialogue and the concept of the greatest dramatic effectiveness, remembering besides that both versions were the work—though at different times and under different circumstances—of the same master. I have entirely orchestrated the onstage musical parts from what existed in the score, which customarily served as no more than an outline for the piano.

The materials used—manuscripts, parts, etc. —were graciously provided by the Library of the Conservatory of S. Pietro in Maiella, that of the Conservatory of Milan, and that of the Donizetti Institute at Bergamo.

Caterina Cornaro was one of those grand Renaissance ladies whose lives prove that truth can be not only stranger than fiction, but more exotic than Italian opera. She was born in Venice in 1454 and at the age of fourteen was contracted to marry James de Lusignan, the illegitimate son of King John II of Cyprus. James, who had seized power in Cyprus on the king's death while the succession was in dispute, desperately needed the support of Venice, which his marriage to Caterina ensured. In 1472, at the age of eighteen, Caterina left Venice for Nicosia with the title of Queen of Cyprus, Jerusalem and Armenia. James died within the year—not, as in the opera, in battle, but from natural causes—leaving his kingdom to Caterina and their child, as yet unborn. Soon after the birth of her son there was a revolution which resulted in imprisonment for Caterina, but she was soon released by a Venetian force sent to restore order to the island. In 1488 another royal wedding was planned for Caterina—to the King of Naples. This was too much for the republican government of Venice, which promptly decided to recall Caterina and take formal possession of Cyprus for itself. Caterina, who had developed a taste for royal life, tried to resist, but she was finally compelled to abdicate and return to Venice. In compensation she was given the castle and town of Asolo for her lifetime, and there she spent her days contentedly queening it over a small but quite brilliant court until her death in 1510. Her memory has been kept alive by Titian's portrait in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence and by at least four operas—Lachner's Catharina Cornaro, Halévy's La Reine de Chypre, Balfe's The Daughter of St. Mark and, most notably, Donizetti's Caterina Cornaro.

Caterina Cornaro was one of those grand Renaissance ladies whose lives prove that truth can be not only stranger than fiction, but more exotic than Italian opera. She was born in Venice in 1454 and at the age of fourteen was contracted to marry James de Lusignan, the illegitimate son of King John II of Cyprus. James, who had seized power in Cyprus on the king's death while the succession was in dispute, desperately needed the support of Venice, which his marriage to Caterina ensured. In 1472, at the age of eighteen, Caterina left Venice for Nicosia with the title of Queen of Cyprus, Jerusalem and Armenia. James died within the year—not, as in the opera, in battle, but from natural causes—leaving his kingdom to Caterina and their child, as yet unborn. Soon after the birth of her son there was a revolution which resulted in imprisonment for Caterina, but she was soon released by a Venetian force sent to restore order to the island. In 1488 another royal wedding was planned for Caterina—to the King of Naples. This was too much for the republican government of Venice, which promptly decided to recall Caterina and take formal possession of Cyprus for itself. Caterina, who had developed a taste for royal life, tried to resist, but she was finally compelled to abdicate and return to Venice. In compensation she was given the castle and town of Asolo for her lifetime, and there she spent her days contentedly queening it over a small but quite brilliant court until her death in 1510. Her memory has been kept alive by Titian's portrait in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence and by at least four operas—Lachner's Catharina Cornaro, Halévy's La Reine de Chypre, Balfe's The Daughter of St. Mark and, most notably, Donizetti's Caterina Cornaro.